‘Throughout the history of the Middle East, Al-‘Ula has been an established commercial route for ancient trade activity….that hosted all trade caravans coming from Southeast Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South of the Arabian Peninsula. These caravans carried all kinds of commodities such as spices, perfumes, and incense. In this connection, the Qur’an says:

‘Between them and the cities on which we had poured Our blessings, we had placed cities In prominent positions, and between them we had appointed stages of journey In due proportion: “Travel therein, secure, by night and by Day.” (Saba’: 18)

Also, from ancient time all the way up to the sixth century, Al-‘Ula was subjugated and dominated by four different states: Didan, Lihyan, Mu’een, and the Nabateans – the Thamud.

We moved northeast of Al-‘Ula to see Al-Khuraibah one of the most important archaeological sites in that area. Here you find many tombs carved into the mountains. The tombs are not alike. Some are simple chambers cut into the rock with rectangular burial places cut into the walls and floors. The interiors of some recalls the tombs of Mada’in Saleh (which I will revert to later) with the difference that the later are more accurately cut and better planned with ornamentation that is more sophisticated.

Other tombs are small cubic chambers that held two graves at the most. Most of them are two metres long and sixty to eighty centimetres wide and seventy to one hundred centimetres high.

Others look like simple rectangular cavities cut into the mountain and designed to hold a single grave. The best known tombs of this kind are the so called Maqaabirul Usuud, Lion Tombs, because of two pairs of lions carved on top of each side of the tomb.

We then moved to the old town of Al-‘Ula which is a unique example of an Islamic city from the classical period. It consists of a walled village of about 800 dwellings around the perimeter of the more ancient castle with narrow winding alleys, many of which are covered to shield the people from the heat of the sun. Most of the foundations of the buildings are stone, but the upper floors are made from mud bricks, while palm leaves and wood are used for the ceilings. Although many of these houses were probably rebuilt over time, their foundation is likely to be from the original construction of the town in the 13th century AD. The houses had no openings on the ground floor other than a fortified entrance.

This old town of Al-‘Ula was built around a high plateau adjacent to the mountain above which is Musa bin Nusair or Umm Nasser Castle. My guide and I climbed to the summit of this castle using the original stairway carved in the rock many centuries ago. From this height, one could see much of Al’Ula as well as watch closely the entire old city. The castle was used as a control point to safeguard the town against any attack, and to alert the population of the coming of any danger from outside, like enemy advance and so on.

We afterwards travelled to Mada’in Saleh – the Capital of the Monuments – which lies about twenty-two kilometres to the north of Al’Ula. The locals also call it Al-Hijr, just as it is in the Glorious Qur’an, in reference to the Thamud people and Saleh, the prophet sent to them. In fact, a whole surah in the Qur’an is christened as Al-Hijr (Surah 15). The people of Saleh have been referred to in verse 80 of the same surah as as’haabul Hijr (The People of the Rocky Tract). For anyone who visits Al-‘Ula and Mada’in Saleh, the rocky country and the spacious fertile valley (wadi) and the plains of Qura are there for all to see.

In his commentary to this verse, Abdullah Yusuf Ali said, ‘The Rocky Tract is undoubtedly a geographical name. On the maps of Arabia will be found a tract called the Hijr, north of Madinah. Jabal Hijr is about 150 miles north of Madinah. The tract would fall on the highway to Syria. This was the country of the Thamud.’

In spite of all these, some academics are searching for archaeological evidence to confirm the presence of Thamud at Mada’in Saleh. There is nothing wrong in looking for proof to substantiate any claim; it is part of knowledge. They can keep searching, but I do not need any archaeologist to confirm to me what I have read in the Qur’an concerning Thamud, more so that I have now visited Al-Hijr and seen for myself all the traits contained in the Book about the people.

The Qur’an (7: 74) speaks about the ability of the Thamud to build for themselves ‘palaces and castles in open plains, and carve out homes in the mountains.’ I saw, in the tour of Mada’in Saleh, this mastery of the Thamud of carving dwellings as well as necropolises for the dead out of mountains. What people describe as ‘tombs’ in Mada’in Saleh cannot all be tombs due to the noticeable differences in their shapes and sizes. Some of them could better be designated as small chambers, living quarters, since no graves were cut into the rock inside them.

These so-called tombs and chambers at Mada’in Saleh are the sites most impressive and most recognised monuments. The site holds ninety-four monumental tombs with decorated façades, thirty-five plain chambers, and more than one thousand non-monumental graves and other stone-lined tombs.

We started with The Diwan during our tour. This consists of a rectangular chamber 12.8 metres long, 9.8 metres wide and 8 metres high, carved into the rock. It has an entrance of 8.85 metres wide. There are carved benches 1.5 metres high and 2.25 metres wide with sitting places incised into them, 45 cm and 15 cm lower than the benches. The benches are reached via stairs carved on either side of the entrance. This Diwan is similar to what Dan Brown, in his latest novel, Inferno, described as a mouseion, in relation to early Greeks, ‘a place where the enlightened gathered to share ideas, and discuss literature, music, and art.’

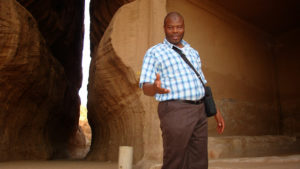

We went to Qasr al-Fareed, which lies in the southeastern part of Al-Hijr. It was called “al-Fareed” (The Unique) because it was cut into a single huge rock; it also includes an architectural element not found in any of the other tombs. The façade of this tomb or chamber (palace) occupies most of the northern side of the rock.

There is Qasr al-Bint on a mountain, which extends from north to south, and contains a group of twenty-nine tombs divided in three sides.

There are nineteen tombs on the western side, one of which was left uncompleted, the mason having started with the upper part of the façade, where the verandas are located, without finishing the rest. Had the façade been completed, it would have been the largest tomb façade in Al-Hijr.

First published November 22, 2013