The image of Northern elites discussing solutions to poverty amidst growing national wealth is not new. This paradox was spotlighted again on September 27th, 2024, during the 17th Pre-Annual General Assembly Lecture of the Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) Alumni Association. The theme, “Hunger and Economic Hardship: A Call to Return to Our Roots and Embrace Innovative Agricultural Solutions,” underscores the persistent crisis plaguing Northern Nigeria. Senator Aliyu Sabi Abdullahi, Minister of State for Agriculture, expressed concern over the region’s deepening poverty despite Nigeria’s 19% increase in GDP per capita. Yet, instead of offering fresh solutions, the Senator’s remarks echoed familiar rhetoric—blaming the past while sidestepping his own role in the region’s failures.

Represented by Prof. Garba Hamidu Sharubutu, the Executive Secretary of the Agricultural Research Council of Nigeria (ARCN), Senator Abdullahi admitted that Northern Nigeria’s poverty has worsened despite the region’s political dominance. He acknowledged abductions and school closures across six northern states in 2021, as UNICEF’s statistics highlighted. But beyond statistics, where is the accountability? It’s unsettling that those who have held power for decades, including the Senator, now decry the region’s problems, conveniently forgetting their prolonged role in its dysfunction.

This portrayal of Northern poverty isn’t new. Politicians and intellectuals have lamented the region’s crisis for years, but meaningful change remains elusive. Instead of pragmatic action, figures like Senator Abdullahi offer only more words, more promises, without the urgency required to salvage the North.

The Same Story, Retold for Decades

Before Senator Abdullahi’s recycled concerns, Nigeria had seen similar warnings. In 2006, Professor Charles Soludo, then Governor of the Central Bank, pointed out in his paper, Poverty: A Northern Phenomenon, that poverty was disproportionately concentrated in the North. Although the report sparked debate, nearly two decades later, the grim reality remains unchanged. Salihu M. Lukman’s critique of the Makarfi administration in 2007, for example, reinforced the need for a governance rethink, but the North continues to stagnate.

Several commentators have since weighed in. Mukhtar Zubairu Sirajo defended Kaduna’s progress under Makarfi’s government, but the overarching narrative remained: development efforts were either symbolic or hampered by weak implementation. Sam Amadi expanded the conversation by examining cultural, institutional, and geographical challenges, reinforcing the deep-rooted nature of the problem. The North’s stagnation was, as Amadi argued, not just a failure of governance but of a political system designed to serve the elite.

Perhaps the most incisive contribution came from Mallam Bolaji Abdullahi, who argued in 2007 that political instability and governance failures lay at the heart of Northern underdevelopment. He was right then, and remains right today: getting politics right is the only way forward. For that to happen, a genuine “elite bargain” is needed—a political compact among the ruling class to enact reforms for societal benefit. Such a compact remains elusive in the North.

The Mirage of Elite Consensus

In Northern Nigeria, the idea of elite consensus remains illusory. The North is deeply divided along ethnic, religious, and class lines, making unity among political and economic elites nearly impossible. These divisions, worsened by historical legacies of power struggles, have fragmented the Northern elite, diluting their efforts to tackle poverty.

Worse still, many in the Northern elite are complicit in perpetuating the structures that sustain poverty. As long as the wealthy live in luxury while the poor languish in squalor, genuine efforts to resolve disparities will remain out of reach. This disparity is not just a symptom of poverty; it is its cause. The luxury cars driving over potholed roads, the mansions towering over slums, and beggars filling the streets all reflect a divided North.

Where is the elite consensus to tackle this? If it existed, it would have already translated into better living conditions for the millions trapped in poverty. This lack of unity among Northern elites is why Senator Abdullahi’s words feel hollow. He represents the class that has governed the North for decades, and their collective failure to address the region’s crisis speaks volumes about the futility of their concerns.

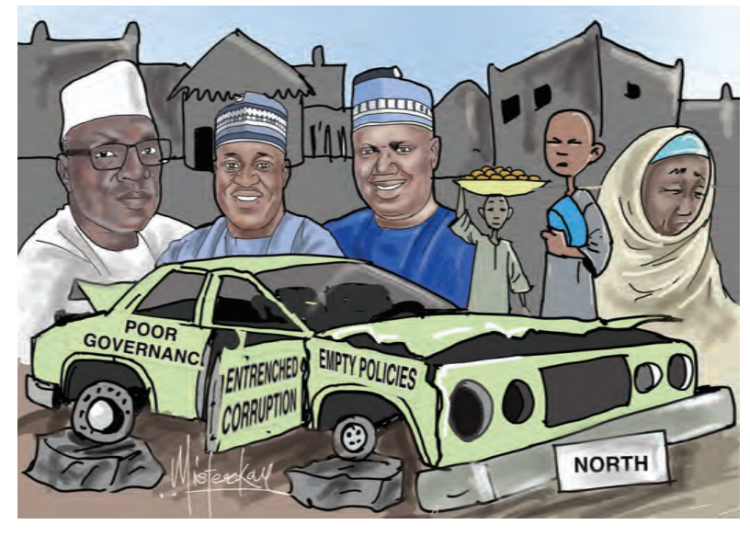

Systemic Failures and Empty Policies

Northern Nigeria’s poverty is no accident—it’s systemic. Poor governance, entrenched corruption, and a lack of political will have blocked genuine progress. For too long, Northern leaders have focused on short-term, cosmetic poverty alleviation measures—programs that look good on paper but deliver little in practice. From micro-credit schemes that fail to reach those in need, to grandiose agricultural projects that never materialize, the cycle of failure persists.

The real tragedy lies in the region’s untapped potential. Northern Nigeria is blessed with fertile land, abundant resources, and a young population that could drive economic growth. Yet, this potential remains unrealized due to a lack of investment in human capital. Education is underfunded, healthcare is inaccessible, and infrastructure is in shambles, making economic activities hard to sustain. The exodus of skilled labour and the closure of 618 schools across six northern states in 2021 signal a broader collapse of the social contract.

Northern Nigeria doesn’t need more poverty alleviation programs; it needs a radical overhaul of its governance structures. Corruption must be confronted head-on, and transparent, accountable governance must prioritize the people over politics. But as long as leaders like Senator Abdullahi continue to offer vague platitudes while evading responsibility, nothing will change.

The Failure of the Elite

In August 2023, I wrote an essay highlighting how Northern Nigeria’s elite has consistently failed the region. It’s not just a failure of governance, but of imagination. The North’s problems are not insurmountable, but current leaders lack the vision to see beyond their political interests. Elite consensus, as some suggest, might be a solution, but it requires more than lip service. It demands a fundamental shift in governance that prioritizes the common good over expediency.

A glaring deficiency of Northern Nigeria’s ruling class is their tendency to reduce poverty to a statistic—something to be managed, rather than eradicated. Poverty in the North is not just socio-economic; it is political. Until the political class confronts this reality, the North will remain stuck in a vicious cycle of underdevelopment.

The numbers are stark: over 70% of the Northern population lives in poverty. This is not a recent development but one that has worsened over the years. The sight of children begging, young men selling fuel in jerry cans, and older people reduced to begging is not just a governance failure—it is a moral indictment of the Northern elite.

A Call for Radical Change

Northern Nigeria stands at a crossroads. The debates of 2007, the speeches of 2024, and the failed policies of the past two decades all point to the same conclusion: the status quo is unsustainable. Acknowledging the problem is no longer enough; a complete rethink of governance and resource management is urgently needed.

The North requires investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Most importantly, it needs leaders willing to prioritize the people’s interests over personal gain. Northern elites must realize that they can no longer afford to rule by exclusion, ignoring the majority of the population. Poverty is not just a statistic; it’s a human tragedy unfolding across Zaria, Kano, Maiduguri, and other cities. The time for talk is over. What the North needs now is action. The question is: will the Northern elite finally rise to the challenge?