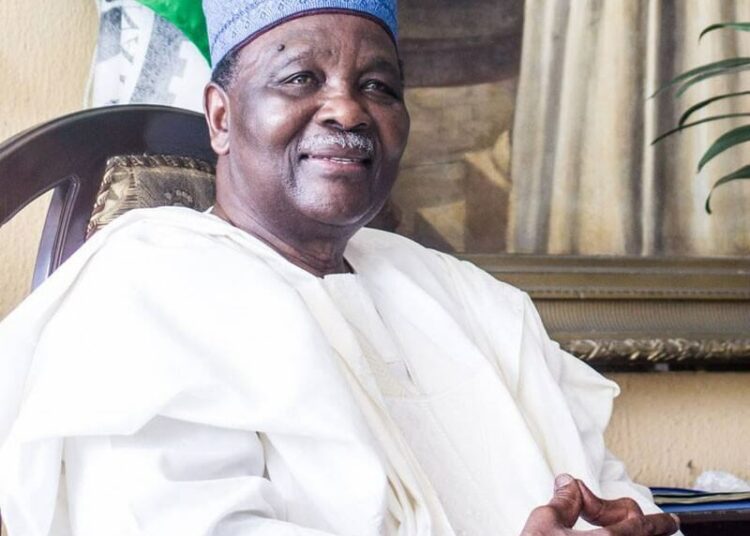

As the legendary Professor Chinua Achebe would write in his magnum opus, ‘Things Fall Apart’, some have their kernels cracked for them by their Chi (god). General Yakubu Gowon surely fits into that characterisation. There is no other way to explain his meteoric rise to fame and power in a country as diverse as Nigeria. At 31, and as a Lieutenant Colonel, he had already climbed the professional ladder to become Nigeria’s second military Head of state after the late Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

It may be convenient to suggest that he benefitted from a crisis generated by the first putsch led by the late Major Kaduna Nzeogwu. Still, it is obvious that providence singled him out for the role he was called upon to play because, even as the chief of staff, Army, the youngest ever on that rank, he was not the most senior in the hierarchy of officers. This significant departure point raised irreconcilable differences within the army itself, especially between him and Lieutenant Colonel Emeka Ojukwu at that time, contributing to a needless 30-month secessionist bid.

It is important to note that he was still unmarried at that time. In present-day Nigeria, by virtue of his marital status, he would have been dismissed as not sufficiently responsible for such an esteemed political position. He proved his mettle and mobilised resources, men, material, and public opinion, local and international, to ensure that Nigeria remained a unified geopolitical entity.

Jack Gowon, as his contemporaries fondly called him, was a principled man raised within the confines of an arcane religious persuasion by a father so disposed and steeped in patriotic fervour. He believed dialogue was a better way of resolving national issues, even in a military situation. It is on record that, based on this disposition, it took him time and intense consideration before issuing the order to fire the first shot that marked the commencement of the hostility glibly described as the Nigerian Civil War.

Just as he had imagined, after the 30-month blood-letting, it still required the meeting of minds around a table to end the conflict. His famous proclamation in his “no victor, no vanquished” speech, which was followed with an amnesty for the majority of those who had participated in the Biafran uprising, as well as a programme of “Reconciliation, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation”, to repair the extensive damage done to the economy and infrastructure of the Eastern Region during the years of war marked him out as a leader in a class of his own.

The National Youth Service Corps scheme (NYSC) still stands today as a testimony to a man’s vision to build a nation from an amalgam of ethnic nationalities. What better way to go about it than to deploy the youthful energy that was and still is so latent and preponderant?

Gowon spent close to nine years in office. Some of his policies in those years have remained controversial till today, such as giving 20 pounds to Biafrans who had a bank account in Nigeria before the war, regardless of how much money had been in their account; the Indigenisation Decree of 1972, which declared many sectors of the Nigerian economy off-limits to all foreign investment while ruling out more than minority participation by foreigners in several other areas and his reneging on earlier promise of handing over power to a democratically elected government in 1976 by declaring that Nigeria would not be ready for civilian rule by 1976 and postponed the process indefinitely. This decision generated enormous bad blood for him, culminating in his overthrow in 1976.

There is no denying that the post-civil war years under his watch saw Nigeria enjoying what later became doom: the boom in crude oil revenue. There were some wastages. However, that period also witnessed an enhanced momentum that yielded massive infrastructural development like roads, airports, expansion of the university system, and many others. The various national development and other rolling plans propelled sustained growth.

Out of power, Gowon displayed a disarming humility when he decided to go back to school. It was then realised that despite allegations of corruption against his government, he did not have enough resources to finance his academic pursuits and depended on the goodwill of former associates.

Gowon himself will admit that his perceived link with the Dimka coup was a blur on his stellar record. Once forgiven and on his return to Nigeria, he has continued to play the statesman’s role, participating in politics in a refined way and essentially praying for the country he gave his all to.

As he turns 90 today, he is admirably upbeat about it, and his friends and admirers celebrate with him. Despite all odds, Gowon will, in his moments of introspection, accept that God has been fair to him. All that is left for this national icon is the judgment of posterity. That, too, we believe, will be gracious to him.

As a newspaper, we join the nation he served to the best of his ability in wishing him many more years of service to humanity

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel