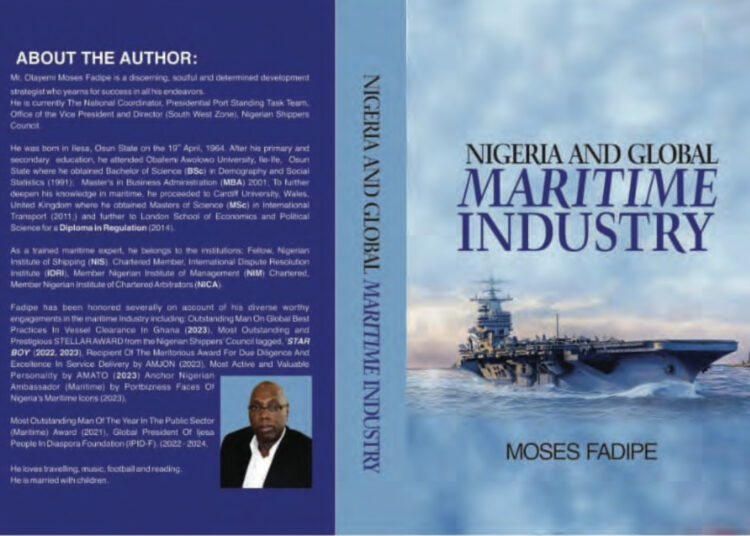

The book is a compendium of activities in the African and Nigerian maritime industry detailing the author’s personal experience and observations spanning more than 30 years as a hands-on administrator. The book which is made up of 13 chapters is a comprehensive vista of activities that have held down the maritime industry and solutions to ameliorate the situation.

Chapter 1 talks of the Maritime Industry and Port Performance in Africa. Here the author x-rays Africa’s place in the global international market place and role of the maritime sector in ensuring that the continent remains a veritable competitor through the movement of export and import of seaborne goods.

According to him, while African international trade relies heavily on shipping and seaports, it is sad that its share of global maritime trade pales in comparison with Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

All these are as result of the continent’s trade concentration and limited diversification brought about by lack of investments in maritime technology.

Chapter 2 is a comprehensive insight of the author’s journey through the maritime industry which started from his early years as Port Officer with the Nigerian Shippers’ Council (NSC) and his growth within the organisation bringing with it enormous responsibilities that include the establishment of the Oyo State Area Office of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council in Ibadan which he headed even as he was General Secretary of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council branch of the Senior Staff Association of Statutory Corporations and Government Owned Companies(SSASCGOC).

His Odyssey encompassed hectic official assignment of building bridges to cater for interests of the organisation and staff.

Even when he was redeployed to the Lagos headquarters, the author did not lower his sight in contributing enormously towards improving relationship between the Nigerian Shippers’ Council and all stakeholders in the Nigerian maritime industry.

Chapter 3 takes a wider view of the dynamics of global seaborne trade to Nigeria. Here, the author makes case for Nigeria to take advantage of her extensive coastline and embark on establishing a vibrant ‘Blue Economy’ for the economic benefits of the country. He maintained that the maritime industry holds immense significance for coastal countries in terms of economic growth, security, and overall development.

Even at that, it is pertinent to note that while 80 percent of world’s merchandise is carried by sea, the shipping industry is still characterised by demand and supply imbalances, volatile freight rates, environmental concerns, piracy and geopolitical risks among others.

The author regrets that despite the huge contributions of shipping to global trade, Nigeria remains a fringe player in the maritime industry. This stark reality is laid bare by the fact that more than 90 percent of Nigerian owned shipping companies have either shut down operations or are barely struggling to survive.

This chapter also takes the reader into reasons for establishment of Shippers Associations in Nigeria and other maritime nations.

Chapter 4 talks on ‘The Morality of Change in Maritime Industry’, whereby the author enumerated reasons for choosing the Nigerian Shippers’ Council as Port Economic Regulator which before then was the remit of the Nigerian Ports Authority(NPA) until 2014.

He stressed that the first challenge encountered by the Nigerian Shippers’ Council after its appointment was to embark on advocacy to change the mindset of those responsible for encouraging illegalities in the port corridors which greatly hampered the ‘Ease of Doing Business,’ thereby making Nigerian seaports unattractive as well as one of the most expensive in the world.

The author stated that due to pervasive corruption in Nigerian ports, foreign ships bound for the country diverted their imports to Togo, Benin Republic and Ghana, while their goods were then brought into Nigeria through illegal routes. The consequence was that Nigeria lost enormous revenues in Customs duties and other port charges.

In addition to these woes, the country witnessed various nefarious activities in the port corridors whereby all manner of security personnel and task force mounted illegal checkpoints to extort money from truck drivers and other port users. To curb such illegal activities, the Nigerian Shippers’ Council harmonised the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to combat maritime offences while improving operational efficiency.

Chapters5,6 and 7 talks about the Expanded Roles of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council and establishment of the Port Standing Task Team(PSTT) which remit is to monitor, enforce and apply sanctions where necessary, our hope is to merge this function with the Council Act to become a unit in the council.

Inaugurated on March 3, 2021 the Task Team is to serve as the operational outfit with a view to entrenching accountability and transparency, ensure compliance, as well as promote integrity in the maritime sector. It is noteworthy to state that in 2021, more than 85 percent of ships that arrived at Nigerian ports and terminals departed without encountering extortions. Moreover, many illegal acts carried out at the ports by both state and non-state actors that hampered unimpeded movement of vehicles and individuals along the ports’ logistics ring were disrupted.

Chapter 8 throws more light on activities of PSTT and its expanded mandate to carry out necessary anti-corruption activities that would help dismantle the illegal networks responsible for the traffic logjam within the port area.

Today, the PSTT programme has not only recorded appreciable success, it has succeeded in making for free-flow of traffic in the hitherto corridors particularly the outlet lanes of Apapa-Ijora Sifax-Orile-Mile-2-Berger-Sunrise-Coconut-Tin Can 1&2-Creek-Road-Apapa Port gate totaling 15.6 kms in 2021-2023.

In chapter 9, the author makes a cogent and compelling case for the establishment of a ‘Blue Economy ‘by the federal government. According to him, the ocean economy has an estimated turnover of US$3 to $6 trillion. This includes employment, ecosystem services, and cultural services. Among this, is the fact that fisheries and aquaculture contribute an estimated US$100 billion per year and about 260 million jobs to the global economy?

What really is a ‘Blue Economy’? According to Navy Commander Daniel Atakpa, past Commandant of the Nigerian Navy Hydrographic School;”It is an evolving maritime ecological concept aimed at the growth, citizens ‘well-being and national development”. There’s no doubt that the Nigerian population is expected to reach 400 million by 2050 which will no doubt exert huge pressure on the country’s resources and infrastructures.

Against this background, the author is advocating an urgent recourse to harvesting the ocean resources to feed the burgeoning population while bringing more revenue for national development.

Without doubt, Nigeria has a coastline of 420 nautical miles and an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles. Moreover, the country is situated in the Gulf of Guinea which confers a huge advantage to exploit the enormous ocean resources within its continental shelf. There’s no doubt that Nigeria has the capacity to operationalise the Blue Economy and make it work for enhanced economic growth. According to experts, Nigeria’s maritime economy has the capacity to create more than 40 million jobs while generating N7trillion revenue annually.

Speculation is that if properly harnessed, the Blue Economy has the capability of replacing oil as Nigeria’s economic mainstay. Following this, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Maritime Organisation of West and Central Africa (MOWCA) have resolved to collaborate to tap into the $1trillion maritime resources of Nigeria and other coastal countries in the region.

Chapter 10 evaluates the potentials of Nigeria’s maritime industry and concludes that its vastness is reason why many international companies expanding into West Africa consider the country as gateway to the region. In addition to being the largest market in West Africa, Nigeria has the largest population (estimated at 200 million people). In addition, the country’s maritime trade was estimated to account for more than 50 percent of all internal vehicular means of international trade.

The Nigerian maritime industry can be described as an all-encompassing sector that embraces all related activities taking place within the country’s maritime environment which include fishing, salvage, towage, maritime transport, ship construction, repairs and maintenance as well as enterprises involved in carrying out these activities.

In spite of such massive activities, the author is at loss knowing why only Lagos ports of Apapa and Tin Can Islands handle more than 70 percent of Nigeria-bound imports despite the fact that the country has seven seaports.

This situation is forcing importers and exporters in the South East, South-South and Northern regions to pick up their containers in Lagos rather than through other seaports closer to their bases of operation.

In Chapter 11, the author narrates his deployment at the Nigerian Shippers’ Council’s Complaints Unit where he was opportune to come in contact with all stakeholders in the maritime industry including Terminal Operators, Freight Forwarders and Truckers.

During this time, he was able to observe firsthand the irregularities being perpetrated at the ports even when he lacked regulatory powers to enforce compliance.

But all these changed when the Port Standing Task Team (PSTT) was inaugurated and he was put in charge of heading it. It is pertinent to restate that the PSTT which commenced operation on March 3,2021in Lagos for Western ports and in Port Harcourt on September 28, 2021 is saddled with the task of addressing irregularities and corrupt practices at the nation’s ports.

Overtime, port users and government operatives compliance levels have increased, thereby reducing all forms of official impunity, abuse of power, extortion and other sharp practices along the port corridors, at terminal and quay sides where ships berth.

Chapter 12 is about how the maritime industry holds the future of survival for the global community. The author backs such argument with extensive statistics. For example, the United Nations (UN) stated that maritime transport is the backbone of global trade and economy.

Also, in 2020, the International Chambers of Shipping asserted that the shipping trade is at the centre of world economy, with a total value of US$14trillion in 2019. In Nigeria, the total annual freight cost which is put at $5 billion to $6 billion, places shipping at the very heart of the country’s economic growth.

In spite of these, the Nigerian maritime industry is plagued by issues such as low capital formation and investment incentives, as a consequence of the industry not being able accord the requisite status and concessions available to other “big” industries. The multiplier effect is that investors have remained wary of placing stakes in the industry, owing to the various risks associated with it.

According to the author, Nigeria is an import-dependent country. So it is crucial that government supports and pays more attention to maritime issues if it is to realise the full potentials and contribute meaningfully to Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Finally, in chapter 13, the author went on excursion of auditing his activities, contributions and achievement in the Nigerian Shippers’ Council. He bemoans the gross inefficiency pervading service delivery at the ports which creates room for opportunistic officials to engage in illegitimate transactions for monetary gain.

For example, corruption in the ports is estimated to cost Nigeria a staggering of N600billion in Customs revenues, financial losses, including a drop of 38-40 percent in industrial capacity.

He therefore advocated for a new policy directive to bolster efficient service delivery, as well as improve efforts to tackle corruption in the ports. His hammer comes down heavily on some Customs officials and port operators function at supply side of the system and so, are influential in manipulating it for and /or against the demand side of port users.

It is the author’s view that the achievements of PSTT have been monumental, as no other agency before it is able to make such progress in the maritime sector. Before the inauguration of PSTT, stakeholders and government officials acted with impunity believing they are above the law. As at now, many port and government officials have been interdicted by the PSTT for illegal enrichment practices while such illegal proceeds have been recovered from them.

In conclusion, the author averred that the Nigerian Maritime Industry has developed over time; even as there are still compelling reasons to further improve the sector to attract potential investments to enhance the country’s economic development. He therefore called for existing legislations to be amended to create more room for foreign participation in the industry.