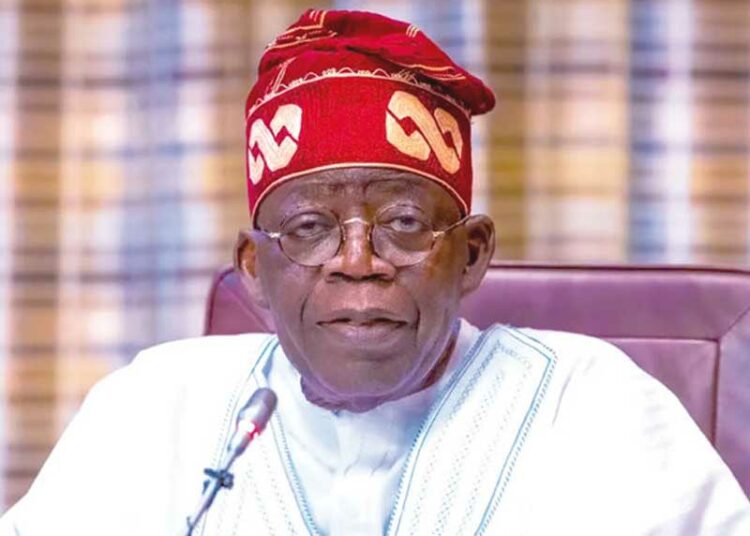

There is a certain irony in the way nations prepare for peace. More often than not, it is forged not at the roundtable but in the workshop — in factories where the clang of steel is as important as the ink on treaties. Last week, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu struck precisely this chord when he declared that Nigeria must manufacture its own military hardware.

Speaking through Vice President Kashim Shettima at the graduation of Course 33 of the National Defence College, the President placed the challenge plainly before the country: if Nigeria hopes to secure its democracy and development, it cannot remain forever dependent on foreign suppliers for the tools of its defence.

It is an old truth dressed in today’s urgency. For decades, Nigeria has struggled with porous borders, insurgencies, and the expensive treadmill of importing arms. Each crisis brings another procurement spree, another round of negotiations with distant manufacturers whose loyalty is never to Nigeria’s survival but to their bottom line. Tinubu’s argument is simple: security cannot be outsourced.

The President was not content with broad rhetoric. He referenced the “Presidential Treaties” produced by the College itself — research blueprints envisioning indigenous manufacturing as a strategic option for national security by 2040. Those papers are more than academic exercises; they are a reminder that ideas are already here, waiting to be harvested and translated into steel, circuitry, and software.

But Tinubu linked the issue beyond guns and gadgets. He tied it to the strength of institutions. “Without strong institutions there can be no lasting democracy,” he said. In other words, factories without frameworks, machines without management, will yield nothing but rust. Manufacturing capacity must be paired with the institutions that sustain it — rule of law, accountability, professionalism, and an economy that rewards competence over corruption.

That is why the President’s insistence that the Defence College itself evolve into a Defence Postgraduate University is more than symbolism. It is about building a permanent home for knowledge, strategy, and research that can outlast governments and weather political transitions.

In a revealing aside, Tinubu pointed to Nigeria’s resurgent stock market — up 48 percent year on year, the strongest performance in nearly three decades. It was his way of saying: confidence is returning, investors believe in the reforms, and there is space now to think long-term.

But he also admitted that inflation and food insecurity remain stubborn thorns. This candour matters, for no nation can build tanks and drones on empty stomachs. The security of the barracks is linked to the security of the farm. The confidence of the investor is tied to the confidence of the citizen buying garri in the market.

If Nigeria must manufacture its own military hardware, it must first feed, educate, and empower the very citizens who will staff those factories and defend that democracy.

The graduates of Course 33 could not have been sent off with a clearer reminder of the times they live in. Their training, Shettima noted, coincided with a world order shaken by war in Ukraine, coups in West Africa, the rise of cyber warfare, and the disruptive energy of artificial intelligence. They leave the classroom not for a stable theatre of command but for a world of “volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.”

And yet, this is exactly why the President’s call for indigenous manufacturing rings true. In such a turbulent environment, sovereignty is measured not just by who casts the vote but by who forges the weapons.

For too long, Nigeria’s defence story has been one of dependence. Our soldiers are brave, our generals experienced, but our supply chains weak. We buy from those who do not share our fate, and sometimes do not share our urgency. Tinubu’s call is therefore not only about industry but about dignity.

But here lies the real test: will these words remain in the comfort of convocation halls, or will they translate into working factories? Will Nigeria build the partnerships between government, academia, and private sector to turn research papers into production lines?

It is easy to speak of 2040; it is harder to lay the foundation in 2025.

There was a moment in the President’s remarks that deserves more attention. He said he had directed the Commandant of the Defence College to work with the Minister of Defence on a clear strategy to upgrade facilities. That, in bureaucratic language, is the first baby step of implementation. But Nigeria’s history is littered with baby steps that never turned into strides.

If this administration follows through, however, then perhaps in 15 years Nigeria will not only be the giant of Africa in population but also in production — a country that builds its own shields as it builds its own future.

For a nation that has long outsourced its protection, that would be a profound rebirth.

In the end, Tinubu’s message was clear: democracy is not defended by slogans, but by soldiers with the right tools, citizens with faith in their country, and institutions strong enough to outlast crises. Nigeria must not just dream of security; it must manufacture it.