Nigeria has enjoyed mixed fortunes in sports over the past 65 years. Considering the array of talent the country possesses, one could argue that it is not enough for a population exceeding 200 million. Nigerian athletes have won a total of 27 medals at the Olympics, comprising three gold, 11 silver, and 13 bronze—primarily from athletics and boxing, with football contributing one gold, one silver, and one bronze.

At the Commonwealth Games, Nigeria’s athletes have amassed a total of 236 medals (70 gold, 75 silver, and 91 bronze), while at the continental level (Africa Games), the tally stands at 1,447 medals (517 gold, 462 silver, and 448 bronze). In football, Nigeria is Africa’s most successful nation, with 58 trophies alongside 29 silver medals and 27 bronze medals in both men’s and women’s competitions. It is a narrative of a nation that once punched far above its weight on the global stage, now watching its sporting fortunes dwindle in tandem with broader national challenges.

Nigeria has long been a powerhouse in African sports. From the electrifying football pitches to the various boxing rings, Nigerians consistently display fervent passion for many sporting disciplines. However, despite its rich history and undeniable talent pool, systemic challenges hinder the country’s ability to achieve sustained progress on the global stage.

The good old days

To understand the depth of the current decline, one must first journey back to the “good old days,” a period stretching from the 1980s to the early 2000s, when Nigeria was a genuine sports powerhouse.

Football: The golden era of the Super Eagles was undoubtedly in the 1990s. The 1994 squad, a constellation of prodigious talents, remains the benchmark. Ranked 5th in the world—a feat unimaginable today—this team, captained by the authoritative Stephen Keshi, featured magicians like Jay-Jay Okocha, finishers like Rashidi Yekini, and stalwarts like Sunday Oliseh and Finidi George. They won the Africa Cup of Nations in 1994 and captivated global audiences at their first World Cup appearance the same year. The pièce de résistance was the Olympic Gold Medal in 1996, where the U-23 “Dream Team” vanquished football giants Brazil and Argentina, boldly announcing Nigeria’s arrival on the international stage.

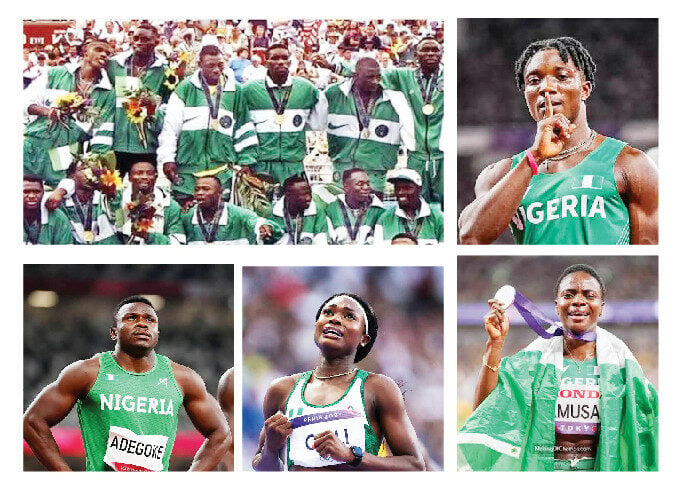

Athletics: The tracks and fields resonated with Nigerian dominance. Chioma Ajunwa’s iconic long jump gold at the 1996 Olympics remains Nigeria’s only individual Olympic gold. The quartet of Davidson Ezinwa, Osmond Ezinwa, Olapade Adeniken, and Chidi Imoh formed a relay team that terrified competitors. Mary Onyali-Omagbemi was a sprint queen, consistently a global podium fixture. At the Commonwealth Games and African Games, Nigeria was a perennial front-runner, challenging for the top spot.

Basketball and Other Sports: The D’Tigers and D’Tigress were competitive, while the real success came from unexpected quarters: boxing produced champions, table tennis had stars like Atanda Musa, and even weightlifting brought home medals. There was a sense of formal success across multiple disciplines.

The precipitous decline

Fast forward to 2025, and the landscape is bleak. The descent has been gradual but undeniable.

Football: The Super Eagles, once a source of fear, are now a wellspring of anxiety. Failing to qualify for consecutive AFCON tournaments (2015, 2017) was once unfathomable. While a runners-up finish in 2023 offered a glimmer of hope, deeper issues persist: inconsistent performances, a glaring lack of cohesive playing philosophy, and an over-reliance on foreign-born players’ individual brilliance. The domestic league, a shadow of its former self, struggles with inadequate funding, poor facilities, and incessant leadership crises. The “Feeder Team” system that produced the Yekinis and Okochas is now comatose.

Athletics: The thunderous applause for Nigerian athletes has become a mere echo. The nation now grapples to secure even a handful of medals at major international events, with the production line of world-class sprinters and jumpers having broken down. The infrastructure—tracks, training equipment, and sports science—remains decrepit or non-existent.

Administrative Quagmire

The most significant catalyst of the decline is poor governance. Sports administration has become marred by political patronage, corruption, and chronic inefficiency. The various national sports federations have devolved into theatres of conflict, with court cases and factional disputes overshadowing sports development. Administrators fixate on senior national teams for short-term glory, utterly neglecting grassroots and age-grade competitions, which are the lifeblood of sustainable success. Tales of embezzlement, unpaid allowances, and budget-padding abound, with funds intended for athlete welfare often disappearing into the ether.

The school sports system that unearthed talents like Segun Odegbami and Falilat Ogunkoya has collapsed. The Principals’ Cup and Headmasters’ Cup are now relics of the past, and there are no functioning youth sports development programs to nurture talent from a young age. Talented youngsters are left to fend for themselves, often relying on individual determination or the goodwill of private academies.

At the recently concluded World Athletics Championships in Japan, Nigeria’s poor treatment of its athletes resurfaced just before the start, with world record holder Tobi Amusan publicly criticising the Athletics Federation of Nigeria (AFN) for providing athletes with poor-quality kits. In a video shared on Snapchat, Amusan expressed frustration, accusing Nigeria’s sports authorities of embarrassing the country on the global stage.

Infrastructure Decay

From the MKO Abiola Stadium in Abuja, with an unplayable pitch despite extensive renovation costs, to the dilapidated National Stadium in Surulere, now a refuge for hoodlums and makeshift worship centres, the physical symbols of Nigeria’s sporting decay are evident. Athletes struggle with limited access to modern training facilities, sports science, and medical support.

The Nigerian government invests significantly in sports facilities and infrastructure development but lacks a strong maintenance culture. Many facilities across the nation suffer neglect due to poor management practices, quickly deteriorating under insufficient upkeep. Without proactive maintenance, facilities face rapid decline, costly repairs, and safety hazards. While Nigeria harbours an abundance of young sporting talent, the absence of structured grassroots programs means that promising athletes do not receive adequate training and exposure, diminishing the country’s talent pipeline.

Corruption

To regain private sector confidence and draw high-profile investors, the government must address corruption in the sports sector. Ahmed Shuaibu Gara Gombe, a prominent sports critic and former chairman of Gombe State Athletics Association, identifies deep-seated issues that undermine sports development at all levels, thwarting the aspirations of passionate athletes and compromising the integrity of the country’s sports federations.

According to Gombe, one glaring manifestation of corruption in the National Sports Commission (NSC) is the lack of merit-based selections within various sporting federations. Coaches, once tasked with identifying talent, are often pressured to favour athletes with connections, sidelining deserving individuals. “This practice denies opportunities to promising athletes while demoralising those who rely solely on talent and dedication. It is common for athletes from privileged backgrounds or with ‘godfathers’ to secure spots on teams, leaving Nigeria’s talent pool largely untapped,” he explains.

The Way Forward

Experts advocate for an urgent overhaul of Nigeria’s national sports policy, identifying management as the crux of the problem. Tolu Ogundeji, a sports sociologist, laments the decay in Nigerian sports as a total collapse of sporting culture. “We no longer have a system that values physical education. Sports is perceived as a pastime for the less academically inclined rather than a viable career. The government views sports as an event-management sector, not a development sector,” Ogundeji contends.

Offering solutions, he emphasises the need for a national sports policy overhaul. “We must legislate and enforce sports in primary and secondary schools, reintroduce competitive inter-school events, and shift the national mindset to regard sports as a vital industry for youth engagement, health, and national branding.”

Richard Terver, a Makurdi-based sports journalist, attributes the decline to administrative incompetence and corruption. “We have square pegs in round holes. Leaders are appointed based on political connections, not expertise or passion. There is a lack of accountability. While the League Management Company (LMC) has tried, it is often sabotaged by the system.”

Proposed solutions include merit-based appointments to bring in experienced sports managers, marketers, and technocrats, alongside a transparent auditing process for all sports federations. Terver insists that public-private partnerships (PPPs) are essential to insulate sports from the government’s financial instability.

Gbenga Bobade, a former athlete, highlights the absence of a proper welfare system for athletes as a major barrier to sports development. “There is no welfare system for athletes. While we had some form of support in our time, today’s athletes are abandoned after representing the country. They sustain injuries with no insurance. How can we expect them to perform when they are preoccupied with their families’ basic needs?”

Bobade advocates for the establishment of an Athletes’ Welfare Commission funded by a percentage of sponsorship deals and government allocations. “This commission should manage insurance, pensions, and post-retirement transition programs for athletes. When athletes are secure, they can focus on winning.”