Hepatitis is now recognised as the world’s deadliest virus after COVID-19, and has become a silent epidemic in Nigeria, affecting an estimated 20 million of her citizens.

It is because of this kind of scary record that the World Health Organisation (WHO) instituted July 28 every year as World Hepatitis Day. This year, it’s imperative that we shine a spotlight on a crisis that has been quietly ravaging the nation.

The theme for this year‘s event, “It’s time to act,” couldn’t be more fitting for Nigeria’s current situation. While the global community has set ambitious goals to reduce new hepatitis infections by 90 per cent and deaths by 65 per cent between 2016 and 2030, Nigeria seems to be lagging behind in this crucial fight.

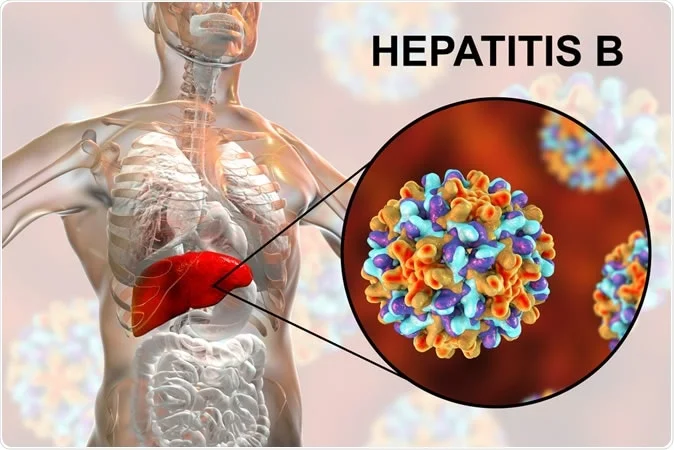

The statistics are alarming: The country has a Hepatitis B prevalence of 8.1 per cent and Hepatitis C at 1.1 per cent making it the highest burden for any infectious disease in Nigeria.

Even of more concern is the fact that 80 per cent of those affected remain undiagnosed, perpetuating the cycle of transmission and increasing the risk of liver-related conditions and cancer.

In the opinion of this newspaper, the lack of awareness about hepatitis in Nigeria is perhaps one of the most significant obstacles we face as a nation. Many of our citizens, particularly in rural areas, are unfamiliar with the disease, sometimes confusing it with hypertension.

This ignorance leads to delayed diagnoses and dangerous self-medication practices, such as relying on unproven herbal remedies that may exacerbate the condition.

Our government’s approach to hepatitis has been woefully inadequate. While HIV/AIDS receives substantial attention and resources, hepatitis – which is 100 times more infectious – has been relegated to the background. This disparity in focus is unacceptable, given the magnitude of the crisis we face.

The financial burden of hepatitis diagnosis and treatment is another critical issue. Unlike HIV testing, which is often free in public hospitals, hepatitis testing remains expensive and out of reach for many Nigerians.

Similarly, while HIV treatment is generally provided at no cost, hepatitis treatment is prohibitively expensive for low and medium-income earners.

In a country where over 80 million people live in extreme poverty, this financial barrier to healthcare is literally a matter of life and death.

The impact of hepatitis on the nation’s healthcare system and economy cannot be overstated. With 1.3 million people dying annually from hepatitis-related illnesses globally, and one person dying every 30 seconds, the human and economic toll is immense.

Nigeria, as one of the 10 countries shouldering two-thirds of the global hepatitis burden, must take immediate and decisive action. So, what steps must we take to combat this silent killer?

First and foremost, the federal government must declare hepatitis a national emergency. This declaration should be accompanied by a significant increase in funding for hepatitis prevention, diagnosis, and treatment programmes. The current level of commitment is inadequate given the scale of the problem.

Secondly, we must launch a massive public awareness campaign. Many Nigerians are unaware of the risks, symptoms, and available treatments for hepatitis. Education is key to prevention and early diagnosis. This campaign should reach into the most remote areas of the country, utilising local languages and culturally appropriate messaging.

Thirdly, hepatitis testing must be made free, compulsory, and accessible to all Nigerians. The government should integrate hepatitis screening into existing healthcare programmes, particularly those focused on maternal and child health. By identifying cases early, we can prevent transmission and begin treatment before the disease progresses to more severe stages.

Furthermore, we must address the issue of vaccine hesitancy. The hepatitis B vaccine, particularly when administered to newborns within 24 hours of birth, is a powerful tool in preventing the disease.

Healthcare workers must be trained to educate parents about the importance of this vaccine and to dispel any myths or misconceptions.

The government should also consider redirecting some of the global funds allocated to HIV/AIDS towards hepatitis management. While both diseases are important heathcare issues, the current imbalance in resource allocation does not reflect the relative threat each poses to public health in Nigeria.

Additionally, we must invest in our healthcare infrastructure to improve the capacity for hepatitis treatment. This includes training of more healthcare workers in hepatitis care and ensuring that treatment facilities are well-equipped and accessible across the country.

Lastly, Nigeria should collaborate more closely with international partners and organizations to leverage global expertise and resources in the fight against hepatitis. We can learn from successful programmes implemented in other countries and adapt them to our local context.

No doubt, we have the tools – vaccines, diagnostic tests, and effective treatments – to combat this disease. What we need now is the commitment to use these tools effectively and equitably.

Pointedly, let us remember that behind every statistic is a human life – a parent, a child, a sibling, a friend. We cannot afford to let another 20 million Nigerians suffer in silence.

Our government must step up, our healthcare system must adapt, and our society must unite in the fight against hepatitis.The path to eliminating hepatitis by 2030 may seem daunting, but it is a journey we must undertake for the health and prosperity of the nation.