The world of economic statistics is often a magician’s stage, where numbers are reshuffled, rebranded, and—on occasion—made to perform dazzling tricks. Nigeria’s recent rebasing of its Consumer Price Index (CPI) is one such spectacle. With a stroke of methodological adjustment, inflation has seemingly plummeted from a harrowing 34.8% to a more palatable 24.5%. This transformation, executed by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), might tempt one to believe that Nigeria’s inflationary inferno has been doused to a simmering flame. But before we break into applause, it is worth asking: Has the economy truly changed, or have we simply changed the way we measure it?

To be clear, CPI rebasing is not a sinister act of statistical manipulation. It is a standard economic practice meant to reflect contemporary consumption patterns. Nigeria’s previous CPI calculations were tethered to an outdated economic reality, much like attempting to measure today’s cost of living using the prices of a bygone era. The new base year—2023—ensures that the index captures shifts in household spending, technological advancements, and the evolving structure of the economy. However, while rebasing provides a more accurate picture, it does not alter the fundamental drivers of inflation. If anything, it merely adjusts the lens through which we view the problem.

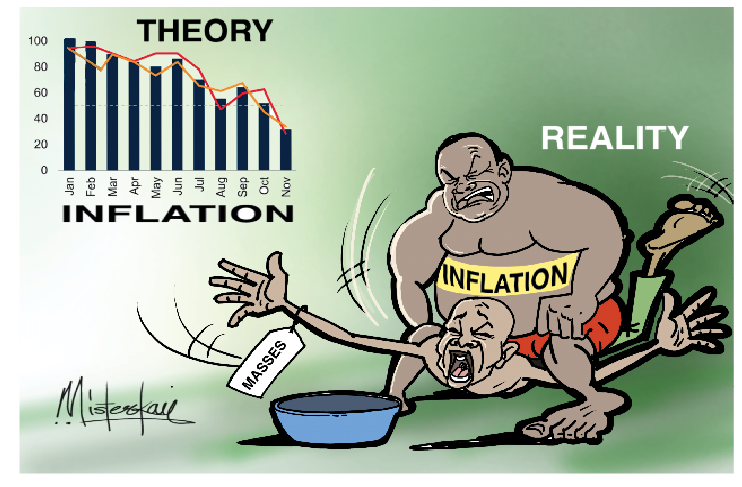

The Illusion of Falling Inflation

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) seems unimpressed by the inflationary illusion. Its Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), in a rare moment of unanimous agreement, opted to keep all key rates unchanged. The Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) stands firm at 27.50%, the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) remains a punishing 50% for Deposit Money Banks, and the Liquidity Ratio (LR) holds steady at 30%. Even the Asymmetric Corridor—a tool that influences how high or low interest rates can fluctuate—was left untouched, ensuring that while the headline inflation rate has been rewritten, borrowing costs can still soar as high as 32.50%.

This decision is not just conservative; it is pragmatic. While annual inflation appears to have declined, month-on-month inflation tells a grimmer story. At 10.7%, this figure suggests that if current trends persist, the economy is still headed toward treacherous inflationary waters. Keeping interest rates high may not be a popular move—especially for businesses desperate for cheaper credit—but it is an acknowledgment that Nigeria’s inflation crisis is far from over. The MPC’s stance is akin to a doctor refusing to lower a patient’s medication dosage simply because their thermometer was recalibrated. The symptoms persist, regardless of how they are measured.

GDP: The Next Statistical Makeover

If the CPI rebasing has offered a new perspective on inflation, the upcoming GDP rebasing promises to reshape our understanding of the economy itself. The last such exercise, conducted in 2014, famously catapulted Nigeria ahead of South Africa as the continent’s largest economy. This was not because of a sudden industrial boom or an influx of foreign investment, but because sectors like Nollywood and telecommunications were properly accounted for in the national output. The impending GDP rebasing aims to do the same—updating economic estimates to include new and growing industries.

This exercise, while necessary, raises some important questions. A larger GDP often serves as a morale booster, convincing both investors and policymakers that the economy is more robust than previously thought. However, it also comes with inconvenient realities. A bigger GDP means debt-to-GDP ratios will appear smaller, providing the government with ammunition to justify more borrowing. At the same time, social welfare benchmarks may be adjusted, potentially leading to the argument that fewer Nigerians qualify for economic assistance. As always, statistics are a double-edged sword: they can reveal progress, but they can also be used to mask underlying distress.

Policy Paralysis: The Elephant in the Room

While statistical rebasing can help refine economic analysis, it does not replace the need for sound policy. Nigeria’s inflation is not a phantom conjured by faulty data—it is a structural problem rooted in supply constraints, fiscal indiscipline, and exchange rate volatility. Yet, the policy responses to these issues remain uninspiring.

Consider the exchange rate. The naira remains at the mercy of market fluctuations, yet policy efforts to stabilize it have been reactive rather than strategic. The government’s sporadic interventions in the foreign exchange market resemble a driver who only tightens their seatbelt after a crash. What is needed is a comprehensive approach—one that combines increased dollar liquidity through export diversification with stronger reserves to cushion against shocks.

Then there is fiscal policy, which continues to play a dangerous game of contradictions. On one hand, the government seeks to curb inflation; on the other, it borrows extensively, fuelling liquidity surges that keep prices elevated. It is the economic equivalent of trying to put out a fire with one hand while pouring gasoline with the other. Until fiscal discipline is prioritized, monetary policy will remain a futile exercise in damage control.

Breaking the Cycle: Real Solutions, Not Statistical Tweaks

Nigeria does not need better statistical models to fix inflation—it needs better policies. Three critical interventions could break the inflationary cycle and set the economy on a sustainable path.

First, food security must be treated as an urgent national priority. A significant portion of Nigeria’s inflationary pressure comes from rising food prices. Rather than endless importation, there should be aggressive investment in mechanized agriculture, climate-resilient farming techniques, and infrastructure to reduce post-harvest losses. If countries like Brazil and India have managed to turn agriculture into an economic powerhouse, there is no reason Nigeria cannot do the same.

Second, energy policy must move beyond rhetoric. The cost of power is one of the biggest drags on business competitiveness. Yet, rather than fixing generation and distribution bottlenecks, Nigeria remains locked in an endless cycle of failed reforms. A country with abundant gas reserves should not be running on generators. The obsession with subsidies, rather than targeted investments in grid expansion and alternative energy, has kept the sector in perpetual dysfunction.

Lastly, fiscal prudence is non-negotiable. The government’s appetite for borrowing must be matched by an equal commitment to efficiency. Every naira borrowed should have a clear return on investment—whether in infrastructure, education, or industrial growth. The current practice of borrowing to fund recurrent expenditure is unsustainable and, frankly, reckless.

The Bottom Line

Nigeria’s latest statistical recalibration offers a fresh perspective on inflation and GDP, but it does not alter economic reality. The rebased CPI may suggest that inflation has fallen, but for the average Nigerian, the cost of living remains punishingly high. Similarly, the upcoming GDP rebasing will likely paint a picture of a larger, more dynamic economy, yet this growth means little if it does not translate into jobs, investments, and improved livelihoods.

At its core, the real challenge is not about how inflation or GDP is measured—it is about how the economy is managed. Numbers can be rebased, recalculated, and reinterpreted, but unless policies address the root causes of Nigeria’s economic woes, the hardship will persist. The Central Bank’s cautious approach is a step in the right direction, but it must be complemented by bold, decisive action from fiscal policymakers. Otherwise, Nigeria will remain stuck in its familiar cycle of statistical optimism and economic frustration—where the numbers look good, but reality tells a different story.