The dust has settled on Edo State’s political battlefield, and Senator Monday Okpebhola of the All Progressives Congress (APC) stands victorious. But let’s not kid ourselves – this wasn’t just another off-season election.

No, the Edo gubernatorial race was a spectacle that gripped the nation, drawing in spectators from far beyond state lines. Why? Because in Nigeria, politics isn’t just a game; it’s a blood sport.

The campaign trail was a toxic wasteland of threats and bravado. Fire and brimstone were promised if defeat loomed. At its core, this wasn’t about the people of Edo – it was a clash of titans, a battle for supremacy between Governor Godwin Obaseki and his predecessor, Adams Oshiomhole. The voters? Mere pawns in their power play.

And now, as predictable as the sunrise, we hear the losers’ lament: “We’ve been rigged out!” It’s a tune as old as Nigerian democracy itself. When politicians win, it’s the voice of the people. When they lose? A grand conspiracy, of course!

Heaven forbids a Nigerian politician ever admit defeat gracefully. They’d sooner claim electoral fraud even if their own family wouldn’t vote for them.

But let’s talk about the real losers here – the silent majority. Out of over two million registered voters, less than 600,000 bothered to show up. That’s not just voter apathy; it’s a democratic crisis. We’re letting a minority decide the fate of millions. Is this the people’s choice, or just the choice of those who could be bothered?

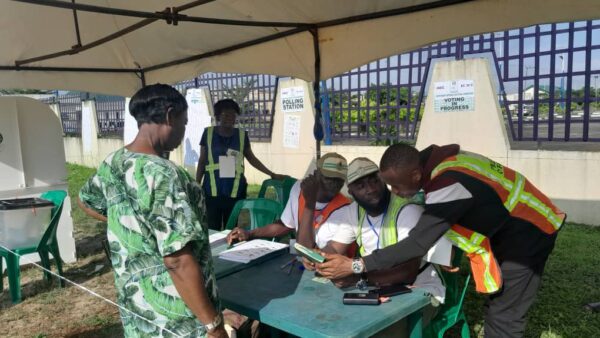

Former President Goodluck Jonathan hit the nail on the head: technology alone won’t save our electoral process. BVAS, IREV – these are just fancy acronyms if the human element remains corrupt. Jonathan spoke of the “dirty attitude” many Nigerians have towards politics. Dirty? That’s putting it mildly. It’s a sewer, and we’re all swimming in it.

Remember the starry-eyed optimists after the 2023 presidential election? “If only IREV had been used properly!” they cried. Wake up, folks. The Edo election had all the tech bells and whistles, and yet the stench of malpractice still lingers.

Our politicians are nothing if not creative in their corruption. They see an obstacle and think, “Challenge accepted!”

Vote-buying wasn’t just present; it was pandemic. Reports suggest voters were the ones with their hands out, demanding payment for their democratic duty. We’ve moved beyond selling our votes; we’re now aggressively marketing them.

So, what are the real lessons from Edo? First, our democracy is sick, and technology isn’t the cure-all we hoped for. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a bullet wound. The rot goes deeper, nestled in the very psyche of our political culture.

Second, voter education is woefully inadequate. When citizens view their vote as a commodity to be sold rather than a voice to be heard, we’ve failed as a society. We need a massive, sustained campaign to rekindle the value of democratic participation.

Third, our political class needs a reality check. The era of treating elections like personal boxing matches must end. When leaders frame every contest as a do-or-die affair, is it any wonder violence and fraud follow?

Fourth, INEC needs more than just technological upgrades. It needs teeth. The ability to disqualify candidates caught in blatant malpractice, backed by swift and severe legal consequences, might make some think twice before reaching for their vote-buying wallets.

Fifth, and perhaps most crucially, we – the people – need to look in the mirror. Our apathy, our willingness to sell our votes, our acceptance of the status quo – these are the fertilisers that nourish Nigeria’s corrupted democracy.

The Edo election wasn’t just a local affair; it was a microcosm of our national democratic ailment. It’s easy to point fingers at politicians, at INEC, at the system. But until we, the citizens, decide that enough is enough, until we refuse to sell our votes, until we show up en masse to have our voices heard – nothing will change.

Democracy in Nigeria isn’t dead, but it’s on life-support. The Edo election showed us the symptoms of our illness. The question is: do we have the will to administer the bitter medicine needed for a cure? Or will we continue this dance, election after election, always complaining about the music but never changing the tune?

The choice, as always, is ours. But if Edo is any indication, we might be too busy haggling over the price of our votes to notice the cost to our nation’s future.