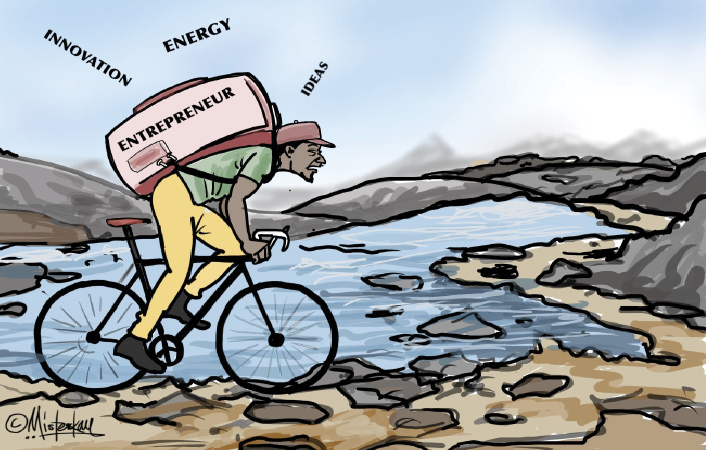

Nigeria’s economy today feels like a bike with a good rider, a decent engine, but a cracked and muddy road. The rider – our entrepreneurs and businesses – is full of energy and resolve. The engine – our resource endowments, labour force, and market size – is capable of great performance. But the road – the systemic structure of governance, policy clarity, infrastructure, and institutional capacity – is in disrepair. Yet, somehow, the bike moves. There is motion, even momentum, but not direction. What the April 2025 Business Confidence Monitor (BCM) shows is exactly this paradox: an economy trying to pick up speed while dragging its tyres through quicksand.

The report indicates a Business Performance Index of +12.29, a marginal improvement from +6.58 in March. There is positive movement in Trade (+25.12), Non-manufacturing (+23.59), and Manufacturing (+8.78), while Services (+6.54) and Agriculture (+7.02) remain modest. These are not just numbers; they reflect the stamina of Nigerian businesses. Despite power outages, forex scarcity, and policy confusion, firms are grinding forward, driven by necessity, not confidence.

But let’s not mistake the spinning of wheels for progress. Beneath these numbers lies a struggling ecosystem. The cost of doing business continues to rise, reaching +51.79. Investment sentiment is negative (-15.00), and price levels have dropped (-16.62), suggesting declining profitability and waning demand. These are warning signs that we are peddling hard on a road that offers more resistance than acceleration. Like a biker exerting energy to stay upright on gravel, the Nigerian private sector is spending its strength on survival, not scale.

Of Riders, Roads and Risk

In Arturo Bris’ The Right Place, he emphasizes that competitiveness stems from the systemic quality of the environment – legal systems, regulatory clarity, infrastructure, and governance – not from raw inputs or enthusiasm alone. Nigeria is failing this test. Businesses operate in a vacuum of clarity. In the April BCM, unclear policies were ranked among the top five business constraints, alongside perennial culprits like poor electricity, limited access to credit, and high rental costs.

The private sector is like a rider on a road riddled with broken signage, unexpected potholes, and erratic detours. One day the CBN says the Naira will float, the next day it subtly intervenes. Tax regimes shift like traffic lights with no countdown. A manufacturing firm importing machinery cannot plan prices, because forex volatility creates a daily guessing game. Even traders, buoyed by short-term boosts from festive seasons, face disruptions in logistics and inventory due to inconsistent port rules and customs bottlenecks. No rider, however skilled, can safely navigate such unpredictability without falling.

Security is another invisible barricade. Whether it is herders invading farms or bandits disrupting supply chains, insecurity has become a hidden cost in doing business. It raises insurance premiums, restricts distribution, and elevates operational risk. In a country where logistics are already expensive, insecurity becomes the final blow that knocks margins into the red. It is difficult to attract long-term investment when every kilometre of road carries a cost in fear.

The Mirage of Optimism

Still, future business expectations remain moderately positive. The April Future Expectations Index stands at +28.98. Trade expects +69.58, Non-manufacturing +48.71, Manufacturing +37.27, with even Services and Agriculture projecting cautious optimism at +19.61 and +24.28 respectively. Firms expect stronger cash flows, better employment levels, and improved profits. These expectations, however, sit on shaky foundations.

Much of the optimism in trade, for example, is tied to seasonal consumption patterns, not structural reform. The April bump was linked to higher spending during two major festivals. When those cycles pass, so does the momentum. Manufacturing optimism comes from export demand and minor public investment in infrastructure. Yet, with an investment index of just +1.50, the sector clearly isn’t receiving the fuel it needs to go the distance. In services, while real estate and professional services showed resilience, the foundational costs – logistics, electricity, exchange rates – remain high enough to choke sustainable expansion.

The danger of such optimism is that it creates a mirage: a sense that the system is healing when it’s only momentarily distracted from pain. Like a biker gliding on a rare patch of smooth asphalt, we forget that the potholes return just around the bend.

Advice for a Government on Training Wheels

What is to be done? The first and most urgent repair must be to Nigeria’s power system. No economy, particularly one reliant on industrialisation and agri-processing, can function on epileptic power supply. Businesses have already adapted by using generators, but this adaptation is not scalable – it is survivalist. Decentralised mini-grids, backed by clear regulations and public-private partnerships, can begin to unshackle industry from diesel dependence. The long-awaited Siemens power deal must go beyond headlines and result in actual grid stability.

Next is policy clarity. Investors and businesses alike can handle bad news; what they cannot handle is ambiguity. The CBN must publish and adhere to a forward-looking forex framework. Tax policies must be consolidated across federal, state, and local agencies to remove duplication and arbitrariness. Regulatory bodies need performance scorecards to discourage impunity. Policy should be a road map, not a roulette wheel.

Access to credit remains a thorn. Development finance institutions must stop operating as bureaucratic silos and instead become responsive, data-driven vehicles for sector-specific lending. Agricultural credit, for example, must be de-risked through technology-enabled collateral systems. MSMEs should be able to access working capital without mortgaging their survival. Banks, for their part, need incentives to fund production, not just consumption or government securities.

Insecurity must be addressed not just with military force but with economic justice. Youth unemployment is a ticking time bomb that breeds restlessness and militancy. Training programs should focus on employability in high-growth sectors—agri-tech, logistics, healthcare, and construction. Insecurity is a social problem with economic roots, and only economic solutions can yield lasting peace.

Finally, infrastructure cannot wait. Roads, broadband, logistics hubs, and affordable housing are the arteries of modern economies. Without them, the heart of commerce cannot pump efficiently. The current capital expenditure budget is too low for Nigeria’s ambition. More importantly, it is poorly targeted and inconsistently executed. The time has come for a national competitiveness dashboard that tracks not just GDP, but road quality, electricity uptime, transaction costs, and institutional efficiency.

A Biker’s Truth, A Nation’s Test

Nigeria is not without strength. It has shown the world that its private sector can hustle, survive, and sometimes even thrive in the most hostile conditions. That is a testament to the rider. But this cannot continue indefinitely. As any biker knows, surviving the ride is not the same as reaching the destination.

The April 2025 data gives us both a snapshot of effort and a diagnosis of stress. We are moving – but the question is, how far can this machine go on a road this broken? If Nigeria wants growth with depth, not just growth by inertia, then it must stop expecting miracles from its bike men and start fixing the asphalt they ride on.

Because at the end of the day, it’s not the rider or the engine that will determine our economic future – it’s the road we choose to build.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel