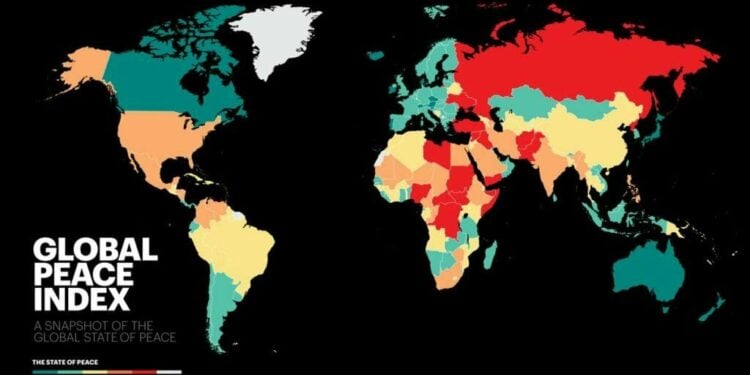

Nigeria’s performance on the Global Peace Index (GPI) between 2021 and 2025 reveals only modest and inconsistent improvements, raising serious concerns about the country’s ability to attract investment and sustain economic growth under President Bola Tinubu’s reform agenda.

Data compiled by CountryEconomy.com show Nigeria’s GPI score slipping from 2.840 in 2021, when it ranked 149th globally, to 2.907 in 2024, with a slightly better global ranking of 147th. A brief recovery was recorded in 2022, when Nigeria’s score improved to 2.845, pushing it to 141st place, but subsequent years reversed the trend. In 2025, Nigeria was again classified among Africa’s least peaceful nations, ranking around 148th globally, with a score of 2.869.

Within Sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria ranked 38th out of 44 countries, trailing behind regional peers like Mauritius, Botswana, and Namibia. That highlights Nigeria being among the 10 least peaceful African countries, placing eighth on that list with a GPI score of 2.869.

Security experts warned that the figures carry significant economic implications. Peace and stability are essential to business confidence, infrastructure development, and foreign investment inflows. The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) reports that global peace levels have declined by about 6 percent over the past 16 years, but Nigeria’s persistent struggles with insurgency, communal clashes, terrorism, and kidnapping have kept it trailing behind many of its African peers.

“Every small gain in the peace index translates to reduced business risks and increased investor confidence. The problem is that insecurity has become deeply entrenched, and unless the government adopts a multi-dimensional approach, combining military, economic, and social measures, the peace dividends that investors seek will remain elusive,” said a security analyst based in Abuja, Dr. Alfred Meruwanne.

The cost of insecurity in Nigeria is already evident. Rising violence in the Northeast, recurrent communal conflicts in the Middle Belt, and terrorism-related risks have increased security expenses for businesses and disrupted trade across key economic corridors.

On the national level, Nigeria’s budget for 2022 was N2.48 trillion. In 2023, it was N2.79 trillion. In 2024, it was N3.85 trillion. And for this year, it is N3.10 trillion. This signals a diversion of capital that could have been invested in infrastructure and social spending on health and education.

For many in the private sector, the situation is becoming unsustainable. “We spend close to 20 per cent of our annual budget on security alone,” said Danladi Muhammed, a logistics company owner in Lagos. “These are funds that should be invested in expanding operations or hiring more staff, but instead they go into protecting our goods and personnel,” he noted.

Foreign investors share similar concerns. A Lagos-based investment consultant, Anita Thompson, observed: “Nigeria has huge potential in manufacturing and services, but peace is the foundation for long-term investment. International clients frequently ask about security before they ask about profit margins, which tells you how much of a risk factor insecurity has become.”

Economists stress that Nigeria’s structural challenge lies not only in policy execution but also in tackling insecurity at its roots. “The government can push reforms in revenue collection, foreign exchange, and infrastructure, but if insecurity persists, the benefits will not be fully realised,” explained Development Economist Dr. Paul Alaje. Investors need predictability, and instability erodes that confidence. “

Nigeria’s GPI performance between 2021 and 2025 serves as a sobering reminder that peace is not guaranteed. While modest improvements have occurred, the overall picture reflects a nation still deeply challenged by insecurity.

Analysts said sustainable economic growth will only materialise when peace and stability are elevated to the same priority level as fiscal and structural reforms.

“Without peace, prosperity remains just out of reach,” stated policy expert Pauline Nwosu. “If Nigeria can achieve even modest gains in stability, the economic rewards could be transformative. But time is running out,” she stressed.