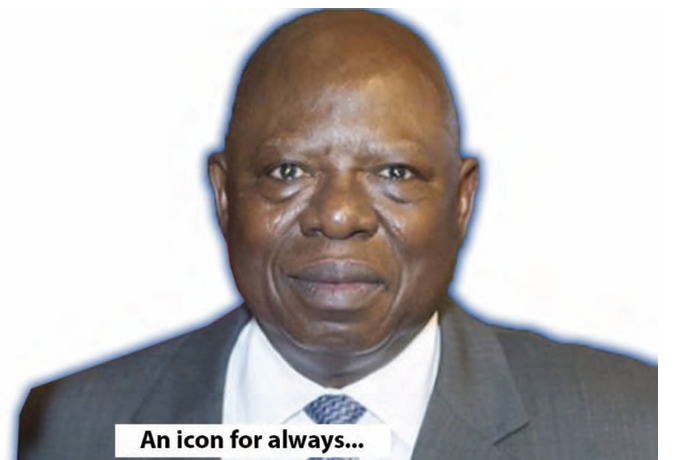

Ten years ago, this article appeared under a different title, “The Debt I Owe.” Professor Olatunji Dare was 70 at the time. Ten years later, on Dare’s 80th birthday on July 17, I’m republishing the article with minor changes.

Without this man, I might have turned out to be a literary plumber or perhaps a motor park journalist, but nothing near the second-eleven of a craft that I owe so much. I have also attached a fairly comprehensive file record of Dare in case my updated article is deficient – as I’m sure it is:

I met him in 1985. I was in Mas 101 freshman journalism class, and it was my first lesson and first encounter with the University of Lagos lecturer.

He wiped the board clean and wrote the course title and his name, “Dr Olatunji Dare”. He then turned to the class and asked us to introduce ourselves and say why we were there. Writing out his name seemed familiar, but asking us why in the class seemed strange.

One by one, we introduced ourselves, each with his own story. Some chose to study journalism to get a big chance to travel far and wide. Some hoped that a career in journalism would bring them face-to-face with rich, influential and powerful people. A few said they wanted to report the rich and powerful and become rich, influential and powerful.

Dare listened patiently, showing no emotion, only motioning from row to row until the last student spoke.

Then silence. I still remember how he shook his head and, with a severe look, said he was either in the wrong classroom or many of us had missed our way.

Journalism could take you places. It could bring you face-to-face with the rich and powerful. It could even make you famous if you worked hard enough, with some luck. But those who thought here at last was the lottery to money, riches, and fame should perish the thought. Our road would be rough, and there was free advice on how to think again.

“And if it would make it easier”, he said, “I’m willing to help you get the Faculty Officer to arrange a change of course for you!”

A number of us didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. No one would likely take up his unsolicited offer of help, but that, for me, was the baptism needed for the journey ahead. Over the next three years, I developed a closer relationship with him and was especially fascinated by his teaching style and commitment to his students.

He would pose out-of-the-text questions and challenge us to solve them; he would ask about journalists whose names we had never heard of, like Oriana Fallaci, and point us to her famous interviews with Ayatollah Khomeini or Muammar Ghaddafi. He would send us out to file reports about campus life, and when we turned them in, he would return our scripts bleeding in red ink.

I still remember Dare refusing to mark our scripts once, and when we pressed him, he responded that the copies were so bad he would have shortened his life by at least 10 years if he read them all!

And boy, was he funny! He would walk into the exam hall and say there was no need to worry about failing. If you couldn’t answer any exam questions, you could write your own questions and answer them—no need to panic or faint in the hall. And he would say it with a straight face!

I remember turning in a term paper in which I had boasted I would score an A. As I submitted my paper in his office at the pre-fab of the Mass Communication building and made to go, he called me back.

There was a visitor with him. “Azu,” Dare began, looking very solemn, “what have you been reading?”

Finally, here is my chance to showcase my latest collections!

“Oh, I have been reading David Copperfield, sir. Copperfield by Charles Dickens.”

He looked up from my script, shook his head, and laughed the way only Dare could laugh – from his stomach up and rocking with delight.

And then, looking at me, he said, “It’s not showing at all! I can’t see any trace of Dickens in your script. This is a classic example of disco journalism!”

He handed back my script and gave me another chance to rewrite it.

I left his office devastated but knew he meant well. The repeat copy so pleased him that he urged me to adapt it for publication under his watchful eye. It turned out to be my first published article in the priceless op-ed page of The Guardian. I’ll always remember.

I have followed his writings since and often imagined myself a wannabe satirist. Once, when he wrote about stalagmites and stalactites in his Tuesday column in The Guardian, I couldn’t figure out where that came from until later found that he taught science subjects in a secondary school before he became a lecturer.

I still remember the note he gave me on the back of his complimentary card to Najeem Jimoh, then Editor of PUNCH. That note gave me a shot at my first vacation job in a newspaper in 1986.

The note would not only land me a vacation job, and later a full-time job, but it would also open the door for me to meet the former chairman of PUNCH, Ajibola Ogunshola, one of the men who would shape my thinking and career profoundly for the next several decades.

…Dare on File

He is one of Nigeria’s best-known journalists, journalism educators, and public intellectuals.

For nearly a decade, he served as editorial page editor and chair of the Editorial Board of Nigeria’s leading newspaper, The Guardian, where his award-winning and wide-ranging weekly column, severe and satirical, attracted a broad, appreciative national audience.

His weekly column for The Nation, now in its 14th year, is of the same vintage and has drawn high praise for its insights and felicity of style. To mark his contributions to journalism and to public discourse in Nigeria, 20 of his contemporaries, colleagues and former students on three continents in July 2014 presented a festschrift on his 70th birthday titled Public Intellectuals, the Public Square & The Public Spirit: Essays in Honour of Olatunji Dare.

In 1995, he was awarded the Louis M. Lyon’s Prize for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, recognising his steadfast commitment to journalism’s best practices.

In 1994, Nigeria’s military government shut down The Guardian because of its editorial outspokenness. The military authorities made it clear that if The Guardian apologised for its past conduct and promised to be less outspoken, it would be allowed to resume publication.

Eager to resume business – The Guardian was the most successful of his many commercial ventures – the publisher, Alex Ibru, led a team of executives to the head of the military government, Sani Abacha, in keeping with Abacha’s demand.

Dare refused to join the team and resigned, pointing out that a newspaper that had always insisted on the importance of the rule of law should not enter into a bargain that effectively eviscerated the rule of law.

Unable to find meaningful media work and facing constant harassment, Dare left Nigeria in 1996 to take up a faculty position at Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois. The Hammet/Hellman Grant for Courage in the face of Political Persecution, presented by Human Rights Watch, recognised that phase of his career.

While teaching at Bradley, he continued to be engaged in journalism, writing weekly columns for attentive audiences in Nigeria and on the Internet. In the summer of 2000, he served as an editorial writer for The Seattle Times, based on a competitive fellowship awarded by the American Society of Newspaper Editors.

Previously, he conducted journalism workshops in Zimbabwe, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Dare earned the first-ever First Class (summa cum laude) degree in Mass Communication from the University of Lagos, Nigeria, where he subsequently became senior lecturer in journalism.

He also holds a Master’s degree in Journalism from Columbia University in New York, where he was the prizeman in Editorial Writing, and a Ph.D. from Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, with twin concentrations in International Communication and Public Policy.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel