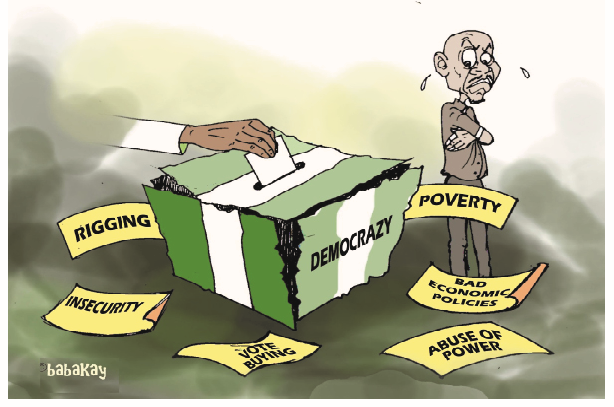

In his Independence Day anniversary speech, President Tinubu said, “By democratically electing a 7th consecutive civilian government, Nigeria has proven that commitment to democracy and the rule of law remains our guiding light.” Nothing could be further from the truth if the definition of democracy is a government driven by the will of the majority and ‘rule of law’ includes respect for human rights. Asides increasing dissatisfaction with the integrity of elections, trust in the judiciary is low after decades of incomprehensible election judgments where judges dispense with justice at the altar of technicalities and Nigeria’s police continue to abuse their power.

Rising Coups In Africa

As we experience a rise in coups and coup attempts across West and Central Africa, kites have been flown about a return of the military to Nigeria to deliver on what democracy seems unable to do. Shortsighted yes, but the perception that ‘democracy is not working’ is not unique to Nigeria. Everywhere, people are complaining about elections lacking in legitimacy, elections that don’t reform much, weak democratic institutions and poor public goods,

Open Society Foundations (OSF) Barometer – Can Democracy Deliver, a survey covering 36,344 respondents and 30 countries including Nigeria, found that 43 percent of those between 18-35 years old prefer other forms of autocratic government to democracy. This suggests that people within this age bracket are losing faith with the politics and inefficiency that comes with elections and democracy especially in the face of many interconnected challenges: failing economies, global warming and rising insecurity. This suggests that instead of heaping opprobrium on those who know too little of the history of the military in Nigeria and other parts of the world, what is required is engagement with the aim of creating more inclusive participatory decision making and ensuring our institutions are more democratic.

Does representative democracy still work?

As trust in national politicians’ declines, 27 percent in Nigeria, below the global average of 30 percent, some forecast that representative democracy as we know it will end. Already in countries like Switzerland, citizens are taking more decisions through regular referendums on everything from tobacco advertising to bans on animal and human experiments. Within cantons, which function like states, the rules around wearing masks in cars can differ depending on what the people in those states want. With more access to information, people want to make the decisions and/or tell their elected representatives what they have decided.

Another finding that should be of interest to Nigeria from OSF’s Barometer is that asides a global average of 62 percent believing democracy is the preferred form of government (69 percent in Nigeria) the majority do not trust that authoritarian governments are more effective at delivering on campaign promises and public services. This means despite growing dissatisfaction with democracy’s ability to deliver, there is an appreciation that democratic governments are better at protecting human rights, promoting global cooperation and reflecting personal values.

This proves that reforms to strengthen democracy would be welcome i.e., adopting proportional representation as our election model, rebuilding trust in the judiciary, securing the independence of the legislature and election management body, and promoting internal party democracy. Unlike President Yar’adua post the 2007 elections, President Tinubu seems unable to admit that the 2023 elections were flawed probably because INEC’s declaration is still being contested but if antecedents are anything to go by, strengthening democracy will not be his priority. However, there are other small(er) ticket items that would improve the perception that Nigeria’s democracy can and will protect human rights: tackling the abuse of the Nigeria Police and Army. That almost 80 percent of Nigerians think democracies contribute more to global cooperation and 65 percent want closer relationships with other democracies should influence our foreign policy agenda and strengthen citizens trust that government listens.

Socio-economic rights rule

Another outcome of the barometer is that Nigerians prioritize economic and social rights. 45 percent of respondents selected economic and social rights as the most important right, next was civic and political rights with 31 percent and environmental and digital rights (ability to communicate online and control one’s personal data) come next at 14 and 7 percent respectively.

This focus on socio-economic rights tallies with a survey by Enough is Enough and SBM on the eve of the 2023 elections on priority governance issues. Insecurity ranked number one at 31 percent and economy next with 22 percent. Both are connected – insecurity is exacerbating a global recession and bad economic policies and inequality and poverty are fueling crime, even amongst those who should be upholding the rule of law. Unfortunately, four months into this administration, asides from the removal of fuel subsidies and related mitigating policies, there is no known economic agenda.

Quality of life for majority of Nigerians needs steady, continuous improvement measurable against all 4 categories of rights mentioned above. More forms of participatory engagement as advocated for and practiced by organizations such as BudgIT will help if replicated by local governments. Unfortunately, local governments in Nigeria barely function due to the refusal of governors to release local government (LG) funds in clear disregard for Section 162 of the Constitution. The recent suspension of Wale Adedayo, LG Chair for Ijebu East, Ogun for accusing Governor Abiodun of mismanaging LG funds is only a recent example of abuse of powers to the detriment of local governance. LGs need to function for the delivery of public goods and services. While advocates for constitutional and electoral reforms continue to engage – including pushing for the adoption of the more radical recommendations made by the Uwais Electoral Reform Committee in 2009 – there is also room for more critical thinking about what the future of democracy should be in Nigeria.

By all indications, citizens – the ones voting and taking polls – are going to have to drive the conversations for better, more inclusive and participatory decision making because those in government have no incentives to reform a system that favors them. As reflections about Nigeria at 63 continue, those opportunities outside the norm are where we need to spend more time imagining and collaborating.