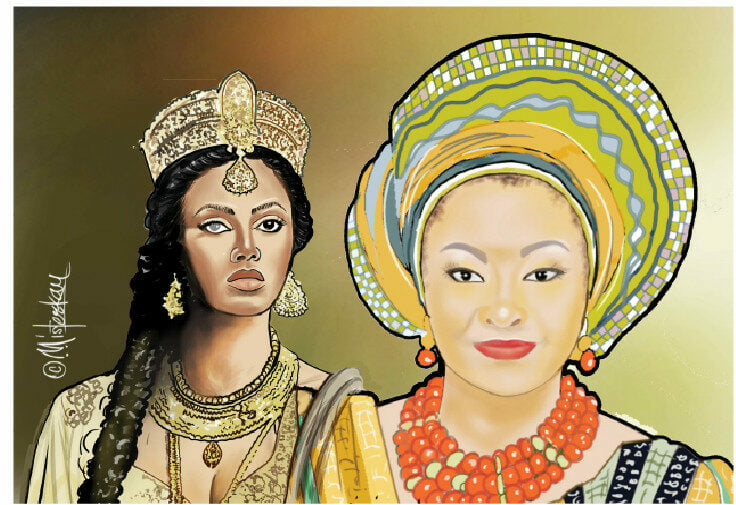

The Biblical Book of Esther tells of Queen Vashti, wife of King Xerxes of Persia. At the height of a grand banquet filled with drunken nobles and courtiers, the king ordered Vashti to appear before the assembly, wearing her royal crown to display her beauty.

Many scholars and interpreters have long debated what exactly the king meant by this summons, but the underlying fact is that Vashti was called not as a partner, not as an equal, but as a spectacle. She was to be paraded for the pleasure of men, reduced to her appearance, her dignity brushed aside. Vashti refused.

In that singular act of defiance, Vashti rejected her objectification. She reclaimed her humanity in a world determined to commodify her womanhood. But her refusal was not without consequence. The men of the kingdom, fearful that her act would embolden other women, conspired to make an example of her. They stripped her of her crown, banished her from the palace, and enshrined in law the supremacy of men over their wives, and by implication, of men over women.

To them, Vashti’s act was not personal but political, not individual but collective. It represented the possibility of women everywhere realising that they had the right to refuse humiliation, to reject the objectification that men had normalised and stand against injustice.

Centuries later, in the corridors of Nigeria’s Senate, another woman stood her ground. Senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan of Kogi Central became the subject of political attacks, suspension, and an insidious campaign of silencing. She accused Senate President Godswill Akpabio of sexual harassment. In response, rather than allowing due process, the Senate moved to suspend her, weaponising institutional power against her voice and, by implication, sending a warning to other women who might dare to confront powerful men or systems of power.

Like Queen Vashti, Senator Natasha Akpoti-Udughan refused to bow, refused to be diminished and paid the price for saying “no.” Now she reaps the reward of her defiance, not just for herself but for all Nigerian women.

Ancient Echoes of Patriarchy, Religion and Culture

In both ancient Persia and contemporary Nigeria, religion, politics and culture are tools for justifying patriarchal control. Vashti’s refusal was framed as a threat to divine and social order, while her banishment was positioned as a moral correction. Even today, in Nigeria, women who speak up are often reminded of “cultural values,” “religious obligations,” or “traditional norms” that insist women must be silent, submissive, and self-effacing.

Yet, scripture itself holds up Vashti’s courage as the spark for a broader story of women’s resilience. Without Vashti’s refusal, the stage would not have been set for Esther to intervene later and save her people. Vashti’s act, though erased by the men of her time, became the hidden root of a story of liberation.

Similarly, in Nigeria, every attempt to silence Senator Akpoti-Uduaghan has paradoxically amplified her voice. What was meant to humiliate her has spotlighted the urgent need for accountability in our political institutions.

Cultural and religious rhetoric in Nigeria often becomes a double-edged sword, used to elevate women as symbols of virtue while simultaneously denying them agency. Women are celebrated as mothers, nurturers, and guardians of morality, yet when they step into political or economic arenas, they are met with hostility, suspicion, and character assassination. That is why the backlash is often swift and brutal.

Political Power and Patriarchal Enforcement

The Senate’s suspension and persecution of Senator Akpoti-Uduaghan is not just about one woman versus one man; it is about the use of institutional power to enforce patriarchal order. Political structures often act as gatekeepers, ensuring that women’s participation comes at the cost of silence and conformity.

Legally, Nigerian women have equal rights. But equality in law can mask persistent inequality in power and consequences. Only four women sit in Nigeria’s 109-member Senate. That tiny minority means that any woman in the chamber who disrupts the status quo is especially exposed.

Consider the irony: in a country where corruption, insecurity, and poverty run rampant, the Senate found urgency not in addressing these pressing issues but in disciplining a woman who dared to allege misconduct. This selective deployment of power underscores how political institutions prioritise protecting male privilege over delivering justice or governance.

Moreover, her ordeal reveals how systemic patriarchy is intersectional with politics. It is not just individual men exerting control but entire institutions, the Senate, political parties, and media echo chambers are all colluding to preserve the status quo.

Women who resist patriarchy often lose more than just position; they face reputational damage, threats, isolation, and sometimes physical harm. Yet, their resistance also plants seeds of change. Vashti’s refusal reverberated into Esther’s courage. Akpoti-Uduaghan’s defiance has emboldened a new generation of Nigerian women to enter politics unafraid, to demand accountability, to refuse silence.

Patriarchy thrives on stories, stories that glorify male dominance, that cast women’s defiance as deviance, that erase the contributions of courageous women. One of the most radical acts we can undertake is to rewrite those stories.

Instead of remembering Vashti only as the queen who lost her crown, we must tell her story as that of the first woman in scripture to publicly resist objectification. Instead of framing Senator Akpoti-Uduaghan as a “troublesome senator,” we must inscribe her name in the annals of Nigerian democracy as a woman who dared to confront legislative power.

By rewriting the narrative, we deny patriarchy the victory of erasure. We keep alive the memory of defiance and create a legacy of courage for future generations.

Toward a Culture of Accountability

Progress towards accountability requires a collective shift. It requires men willing to relinquish the privileges of patriarchy. It requires women standing in solidarity with one another, refusing to let any woman’s defiance be dismissed as her personal battle. It requires citizens who demand that governance be about service, not self-preservation.

The courage to say “no” to injustice is a radical act in any patriarchal system. It is also the beginning of liberation. Vashti lost her crown but kept her dignity. Akpoti-Uduaghan faced suspension, but she retains her voice, her conviction and now her legislative office.

The question before us, as a society, is whether we will continue to punish women for their defiance or whether we will finally dismantle the systems that make defiance necessary. If we are honest, the fate of our democracy, our culture, and our humanity depends on our answer.

Vashti’s story reminds us that resistance, even when punished, can seed future liberation. Akpoti-Uduaghan’s ordeal, too, is bigger than her. It forces Nigeria to confront whether its democracy protects power or principle, and whether its culture will silence women or finally hear them.

The stakes go beyond one senator. Nigeria’s Senate has just four women. If they cannot safely challenge injustice, the message to aspiring female leaders is stark: silence or sacrifice. As Vashti’s refusal set the stage for Esther’s later courage, so Akpoti-Uduaghan’s defiance has emboldened a new generation of Nigerian women to step into politics and refuse silence.

A fresh turn came on September 23, 2025. The Senate has now unsealed Akpoti-Uduaghan’s office, and she has regained access to the National Assembly premises — a necessary step toward resuming her legislative duties.

This matters for more than symbolism. Sources say this decision followed pressure from civil society, media protests, legal action, and international and national outcry.