On a humid Wednesday afternoon in the hallway of a university hostel in Karu, Nasarawa State, Favour Luka stood paralyzed with disbelief. Her skirt, modest by most standards, was seized, not for being too short or flashy, but as punishment for her dyed brown hair, which she refused to dye black. A 300-level student of Bingham University, Favour recalls the moment as more than just rule enforcement. For her, it was a humiliation.

“Honestly, I don’t see why the university should dictate what we wear. We are adults, not kids. As long as I’m not indecent, why should my hair or skirt be an issue?” she said, her frustration still sharp days later.

Favour’s story is part of a growing outcry from Nigerian students who feel trapped between institutional expectations and personal autonomy. Across the country, dress codes remain one of the most hotly contested policies in tertiary education, deeply enforced in some universities, barely acknowledged in others, but never far from controversy.

A Shifting Landscape

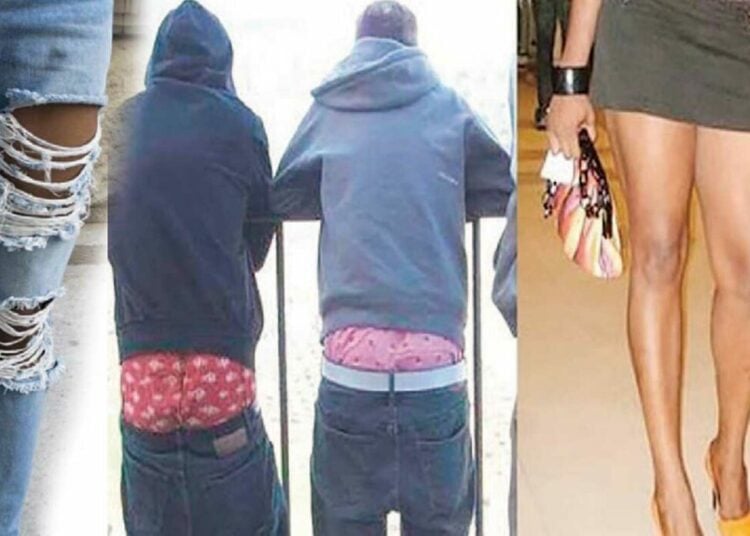

Recent developments in some states are rekindling the fire. In Abia State, Gregory University updated its dress code in early August 2025, banning dreadlocks, sagging trousers, short skirts, and colorful hair. Meanwhile, Lagos State University (LASU) made headlines after suspending several students for repeated violations of its “Decency Guidelines,” a policy that includes clothing, piercings, and even tattoos. In Abuja, Veritas University recently revised its code after protests broke out over what students called “targeted shaming.” The updated version now encourages “modest dressing,” but with fewer specifics, granting both students and faculty room for interpretation—and raising questions about clarity and consistency.

Discipline or Discrimination?

To some students, like Maryjane Onyeke of Babcock University, the dress code debate is not about repression, but readiness. “I actually support the dress code policy,” Maryjane said. “It creates a sense of professionalism. In the real world, we’ll work in offices that expect standards. Plus, in our society, modesty shows respect.” Her argument reflects a belief held by many: that a university is not just about academic freedom but personal development within a structured framework.

It’s a sentiment echoed by parents, like Mr. Dan-Abu Vincent, whose daughter attends Ave Maria University. “When I see students dressed modestly, I feel confident in the environment. The dress code protects them and maintains the reputation of the university,” he said.

But not everyone agrees with that protection-versus-freedom framing. Some students see enforcement as arbitrary and even harmful. Wisdom Bako, a final-year student at Bingham University, takes a more measured stance. “I get why there should be a standard,” he said, “but the way it’s enforced is the problem. One lecturer ignores you, another embarrasses you for a sleeveless top. It’s inconsistent and unfair.”

This inconsistency is a recurring theme across campuses. What’s considered acceptable in one department might spark disciplinary action in another. For students, it can feel like walking a minefield, never quite sure when or where the next confrontation will happen.

The Institutional View

From the perspective of university administrators, dress codes are about more than just appearance. In a statement from Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), the school’s registrar, K. A. Bakare, defended the institution’s policy, emphasizing that it aims to “enhance academic sensibilities, social decency, and ethical standards,” in line with the university’s core values. The statement read, “We’re not trying to police fashion; we’re instilling responsibility, modesty, and discipline.”

Yet critics argue that such policies often reflect deeper societal tensions, particularly the struggle between traditional Nigerian values and the modern push toward individual expression. A media analyst and social commentator, Zuleihat Chatta, sees the dress code debate as a window into Nigeria’s cultural identity crisis. “Universities aren’t just schools; they’re social institutions. Dress codes are about shaping future citizens. But the balance is fragile. Overdo it, and you risk alienating the very generation you’re trying to guide.”

The Real Cost

For students like Favour, that alienation is deeply personal. What started as a conversation about hair color ended in public embarrassment and a lasting sense that her voice and dignity were secondary to rigid rules. “That day, I felt small, like my humanity didn’t matter,” she said. And she’s not alone. On TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter/X, student testimonies ranging from unfair punishments to dress-code-related suspensions are sparking a broader national dialogue.

Has the time come to revise these policies in light of changing societal norms? Or should universities hold firm in defense of their institutional and cultural values? Mrs. Angela Ibe, a civil servant and mother of a 19-year-old student at Covenant University, believes that strict dress codes are essential in maintaining moral values on campus: “My daughter is at a stage where she’s still figuring herself out, and I believe structure helps with that,” she said firmly. “The world out there is already filled with pressure to dress a certain way. If universities don’t draw the line, students may get lost in the wrong kind of freedom. Dress codes are not about oppression; they’re about teaching boundaries and self-respect.”

Mr. Samuel Ekanem, a software developer and father of a student at the University of Lagos, holds a different view: “I trust my son to make choices that reflect who he is. University should be about discovering yourself, not conforming to someone else’s idea of decency. If we keep policing students over how they dress, we risk killing their confidence and creativity. Education should liberate, not limit,” he explained.

These fictional voices add dimension to the article, showing how even parents often assumed to be on the side of tradition can have nuanced, divergent views on how universities should guide or trust their children.

A Nation At A Crossroads

Nigeria’s universities now find themselves at the center of a generational crossroads. With increasing pressure to compete globally while upholding local traditions, dress codes are more than just about clothes; they’re about identity, authority, and the kind of society the country wants to build. In this space between modesty and self-expression, between rules and resistance, students, parents, and institutions are all navigating a delicate balance—one that’s not just about how young people dress but about who they are allowed to become.

It is unclear whether these dress codes are safeguarding tradition and discipline or are relics of outdated thinking that stifle individuality in spaces meant to nurture it.