By all appearances, Donald Trump is reprising the same economic strategy that defined his first administration: a nationalist reordering of trade, a fixation on transactional diplomacy, and a zealous desire to run the United States like a boardroom enterprise. But unlike 2016, Trump’s second-coming economic vision is more ideologically hardened – and potentially more perilous.

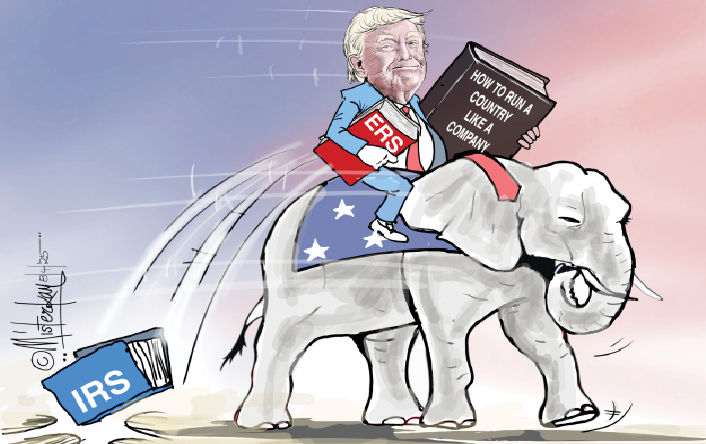

Nowhere is this clearer than in his plan to dramatically escalate tariffs on foreign imports and abolish the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), replacing it with a so-called “External Revenue Service” (ERS) – a new agency that would raise the bulk of federal revenue through border taxes rather than direct income taxes. At the same time, Trump has stacked his economic cabinet with financiers and market-makers: Scott Bessent, a hedge fund manager, as Secretary of the Treasury, and Howard W. Lutnick, chairman and CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald, as Secretary of Commerce. Neither man has served in public office. Both have built their careers in the high-yield, high-volatility corners of financial markets.

In many ways, these developments make economist Paul Krugman’s prescient 1996 essay in the Harvard Business Review, “A Country Is Not a Company,” more relevant than ever. Krugman warned of the dangers of applying corporate logic to sovereign governance. The goal of a company, he wrote, is to maximize shareholder value; the goal of a country is to balance social welfare, national interests, and long-term development – often in the face of complex, even conflicting, public priorities. These are not semantic differences. They are the very lines that separate sustainable statecraft from performative populism.

The Return of Tariff Economics – and the Misreading of History

Trump’s proposed across-the-board tariff of 10% on all imports, and 60% on Chinese goods, is being sold as a silver bullet for American manufacturing and a corrective to trade “cheating.” But this strategy is rooted more in nostalgia than economic reality. In effect, Trump is attempting to reintroduce a 19th-century industrial policy in a 21st-century global economy. And he is doing so with economic advisors who, frankly, appear to be poor students of economic history – if they’ve studied it at all.

Consider Scott Bessent. A former chief investment officer at Soros Fund Management, Bessent is a master of capital flows, arbitrage, and portfolio hedging – but there is little in his résumé that suggests deep knowledge of macroeconomic management, monetary-fiscal coordination, or international trade regimes. Howard Lutnick, meanwhile, has spent decades building one of Wall Street’s most aggressive trading platforms. While this background might offer insights into financial engineering, it offers little understanding of supply chain geopolitics, labour markets, or trade diplomacy.

Tariffs are not simply a lever to “balance” a ledger. They are a geopolitical instrument with far-reaching economic consequences. The last time America tried a similar approach on a broad scale was under the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. Intended to protect American agriculture and industry during the Great Depression, the Act instead triggered a wave of retaliatory tariffs from key trading partners, collapsed global trade by 66% in just three years, and deepened the worldwide economic crisis. If Bessent and Lutnick had spent time studying this period, they might know that tariffs are often less a tool of protection than a spark for escalation.

Moreover, the Trump team’s framing of the trade deficit as a “loss” betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of international economics. The United States has run trade deficits for decades, largely because of its role as the issuer of the global reserve currency and its high consumer purchasing power. These deficits are not inherently negative; they reflect capital inflows, investment opportunities, and domestic demand. Economies are not zero-sum games. One country’s imports can fuel another’s exports and vice versa. In the era of complex global supply chains, punishing foreign suppliers often boomerangs onto domestic producers who rely on foreign components.

The Problem with ERS: Misaligned Incentives and Economic Delusion

The proposal to replace the IRS with the External Revenue Service is perhaps even more concerning. The logic, according to Trump’s team, is to simplify the tax system, shift the burden from income to imports, and “make foreigners pay for America’s prosperity.” On paper, it sounds bold. In practice, it is dangerously simplistic.

Tariff-based revenue models harken back to pre-industrial economies. The last time tariffs were the primary source of federal revenue in the U.S. was before the Civil War. In the modern economy, income taxes provide not just funding, but economic signals, redistributive power, and policy levers. Shifting the tax base to imports disproportionately hurts low- and middle-income Americans, who spend a greater share of their income on goods. According to the Tax Foundation, a flat 10% tariff on all imports could reduce GDP by 1.4%, eliminate 500,000 jobs, and increase consumer prices by an average of 3–5%.

More crucially, such a model would create perverse incentives for revenue generation. Under ERS, the federal government’s fiscal health would depend on sustaining, or even increasing, imports. But this contradicts Trump’s “America First” push to reshore supply chains and reduce dependency on foreign goods. If ERS is successful in reducing imports, it undermines its own revenue base. If it fails, it entrenches inflation and weakens domestic industry. Either way, it creates a structural misalignment between fiscal policy and economic strategy.

Geoeconomics Is Not a Marketplace

In the world of geoeconomics, power flows not only from guns and gold, but from integration, standards, and interdependence. China, the EU, and emerging economies understand this. Trade is not just commerce – it is influence. By imposing unilateral tariffs and withdrawing from cooperative trade regimes, the United States is not asserting strength; it is ceding leadership.

The Biden administration, for all its flaws, has attempted to build multilateral coalitions through initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and renewed engagement with the WTO. These efforts acknowledge that the U.S. cannot decouple from the world economy without losing strategic leverage. Trump’s approach, by contrast, seems to embrace decoupling as a virtue.

What Bessent and Lutnick fail to grasp is that economic power today is networked. Supply chains are strategic assets. Standards-setting in areas like AI, semiconductors, and green energy will define the future of power. Raising tariff walls and monetizing imports will not rebuild American industry – it will isolate it.

Leadership Requires Statecraft, Not Shareholder Management

The underlying flaw in Trump’s economic vision – and in the minds of his chosen lieutenants – is a deep conflation of public leadership with corporate management. But nations do not have shareholders; they have citizens. A firm can cut costs by laying off workers or outsourcing production. A country cannot afford to do the same without triggering social instability, political backlash, and long-term economic decay.

The United States requires more than transactional thinkers. It needs statecraft rooted in an understanding of global interdependence, economic history, and long-term value creation. The obsession with tariffs, the fantasy of ERS, and the rise of financial technocrats without public service experience represent not bold reform – but brittle thinking.

Krugman warned us nearly three decades ago that a country is not a company. Today, that warning reads less like theory and more like prophecy.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel