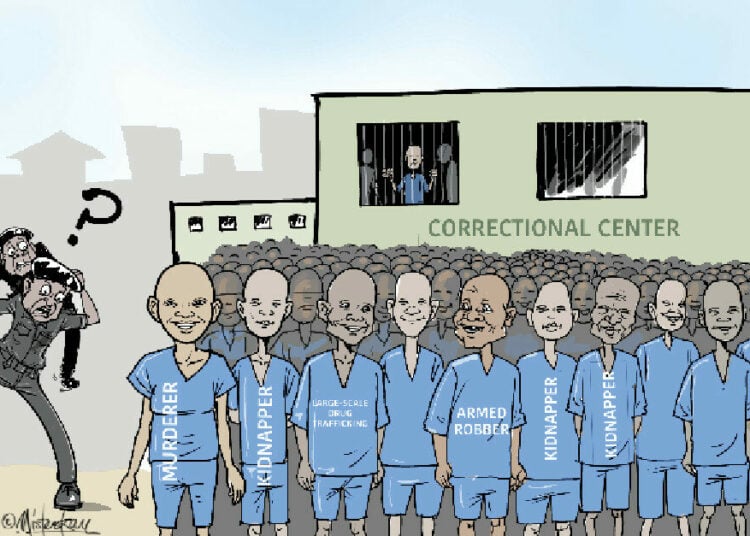

Every nation has its rituals of irony, but few perform them with Nigeria’s flair. When the list of over a hundred people granted presidential pardon emerged, the country momentarily froze — not from surprise, but from the weary recognition of a pattern. Among those resurrected from legal oblivion were convicted murderers, armed robbers, kidnappers, and drug traffickers — people whose names once stained the national conscience. And there, nestled amid the chaos, was Maryam Sanda, convicted of killing her husband and sentenced to death, her case still pending before the Supreme Court.

In a nation where the rule of law already limps, the idea that mercy could outpace justice is both absurd and alarming. Section 175 of the Constitution grants the President the prerogative of mercy — a noble power to forgive, to temper law with compassion. But even mercy has manners. It waits for finality. It respects process. It does not interrupt a judge mid-sentence to say, “Never mind, I’ve decided.” Yet, in Nigeria, the executive seems to believe that compassion need not consult the courts before taking a bow.

It is as if the law were a suggestion, not a structure. And the judiciary — once the last fortress of impartial reason — has been reduced to a spectator, watching its own relevance erode with every politically convenient pardon.

A History of Dangerous Kindness

History is generous with examples of pardons that altered nations — for better or worse. Julius Caesar, ever the populist, granted sweeping amnesty to his enemies in the Senate, only to be stabbed by the very men he spared. King Charles II of England, after the Restoration, pardoned thousands of former Cromwellian soldiers, believing mercy would heal the realm. It did not; it merely postponed rebellion. Even in the United States, President Andrew Johnson’s post–Civil War pardons to Confederate leaders were so controversial they nearly destroyed his presidency.

Mercy, in politics, has always been a delicate instrument — to be used sparingly, lest it turn into farce. Yet Nigeria’s modern version reads like a parody of history. We have taken the nobility of clemency and wrapped it in bureaucratic convenience. When those convicted of murder, kidnapping, and drug trafficking are forgiven en masse without transparent criteria, the gesture ceases to be compassion; it becomes complicity.

Maryam Sanda’s case, still before the Supreme Court, highlights how reckless this newfound generosity has become. Across the world, domestic homicide — particularly intimate partner murder — is rarely pardoned unless wrongful conviction is proven. It is one of the few categories of crime where even monarchs and presidents tread lightly. To pardon such a case while appeals are ongoing is to write a preface to a book the courts have not finished reading.

Guns, Gold, and Political Grace

If the murder pardons raise eyebrows, the forgiveness of armed robbers and gunrunners shatters all logic. Among the beneficiaries are Malam Ibrahim Sulaiman, Major S.A. Akubo (linked to over 7,000 illegal weapons), and Nnamdi Anene, all convicted of serious firearms offenses. For a nation whose headlines bleed daily with reports of killings, banditry, and terrorism, this feels like rewarding arsonists for knowing where the fire exits are.

Globally, nations draw a firm red line around violent and security-related crimes when considering clemency. Even the Vatican, which has made mercy a spiritual virtue, does not advocate pardons that compromise the safety of the flock. Yet in Abuja, the script appears inverted: those who endangered the state are rehabilitated, while citizens remain endangered by the state’s leniency.

One imagines the ghost of Niccolò Machiavelli smirking somewhere: “If you pardon those who arm chaos,” he might whisper, “do not be surprised when chaos arms itself again.” The logic of governance, he taught, lies not merely in the ability to punish, but in the wisdom to forgive selectively. Nigeria, in this moment, seems to have forgotten both.

Even the nation’s law enforcement agencies must now feel a strange humiliation. How does the NDLEA explain to its officers — men and women who risk their lives seizing cocaine, intercepting heroin, and chasing traffickers through jungles — that some of those they helped convict have been pardoned from above? One can almost picture Buba Marwa, the agency’s respected chairman, reading the pardon list like a tragicomedy script, pausing at the names of drug dealers, whispering, “Surely this must be satire.”

Kidnappers and the Art of Forgetting

And then, there are the kidnappers — those whose trade has become Nigeria’s most flourishing underground industry. Names such as Chisom Francis Wisdom, Kelvin Oniarah Ezigbe, and Frank Azuekor reportedly adorn the presidential scroll of forgiveness. Their inclusion feels almost sacrilegious. Kidnapping in Nigeria is no longer an isolated crime; it is a national condition. It has turned highways into death traps and farms into forbidden zones. Parents pack prayers along with lunchboxes when children leave for school.

In countries where kidnapping epidemics have occurred — Colombia in the 1990s, Mexico in the 2000s — no leader dared pardon convicted kidnappers unless part of a negotiated peace settlement. Such acts were carefully structured, conditional, and transparent. But Nigeria’s gesture arrives unanchored — not tied to reconciliation, rehabilitation, or revelation, just quietly inserted into the machinery of state mercy.

This is where the humor of the absurd meets the sorrow of reality. Imagine the irony: ordinary Nigerians still crowd police stations begging for updates on kidnapped relatives, while their abductors may already be back home, forgiven by decree. History will struggle to explain how a country could pardon what it has not yet survived.

Mercy Without Method

Mercy is supposed to be the most beautiful face of justice, the smile that follows the stern gaze. But beauty becomes grotesque when it forgets proportion. The pardon power is not ornamental; it is constitutional surgery. It demands precision, empathy, and restraint. In most democracies, the process involves layers of scrutiny: recommendations by justice departments, reviews by pardon boards, and public transparency. Nigeria’s version, however, is an opaque ritual performed behind closed doors, where mercy appears to be measured not by merit but by connections.

What emerges from this pattern is a deep institutional malaise — a state so entangled in its own contradictions that it no longer distinguishes between compassion and carelessness. A government that pardons murderers while victims’ families still grieve does not inspire unity; it inflames despair. A government that forgives armed robbers while citizens barricade their homes does not heal wounds; it deepens them.

History offers many cautionary tales. When Louis XVI of France began granting arbitrary pardons to nobles convicted of crimes, the act was seen not as mercy but as mockery of common justice. The public’s rage swelled until the guillotine became the only symbol of equality left. When Emperor Nero pardoned his own courtiers after crimes of blood, Roman historians noted that Rome did not forgive him in return. The state that trivializes justice always finds its own legitimacy on trial.

There is humor in tragedy, yes — a kind of dark comedy that Nigerians have perfected. But even satire has limits. The nation cannot continue to laugh its way through institutional decay. The Constitution was not written for improvisation; it was meant as choreography, every branch of government moving in harmony. The President may have the right to pardon, but that right is fenced by reason.