The fruit does not fall far from the tree.

I’ve thought about this saying a lot since I read two books in succession. Ayobami Adebayo’s, A Spell of Good Things and Chika Unigwe’s, The Middle Daughter – both books are about families, and both center women as daughters, mothers, wives, sisters within and outside the boundaries set by norms and personal agency.

The original phrase, ‘the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree’, is credited to Ralph Waldo Emerson essayist, poet and philosopher, who in turn was inspired by an old German proverb, ‘the apple never falls far from the stem’. The understanding is that children will be like their parents; in character, mannerisms, belief and even biology – which is why if a parent has a certain disease, a child is considered at risk. This sense of ‘lion no dey born goat’ is accepted in most cultures. It is likely that long before 1839 when Emerson’s quip was recorded, that the Igbo were saying: “Nne ewu na ata agbara, m ya ana eleya anya n’n” i.e., “When a mother goat is chewing grass, the kid is watching her mouth.”

In A Spell of Good Things, Kunle Coker, the son of doctors used his fists to communicate with his partner Wuraola Makinwa because that is how his father treated his mother, a professor of medicine. Nani, the middle daughter, only shook off the shackles of her upbringing, more precisely her mother’s judgement, to leave an abusive relationship when she realized that her three children were growing into sanctimonious zealots like their father, who masks cruelty with bible verses. She could already see how closely ‘Ọmọ tí ẹkùn bá bí ẹkùn ni jọ’ (The leopard’s offspring will always resemble it).

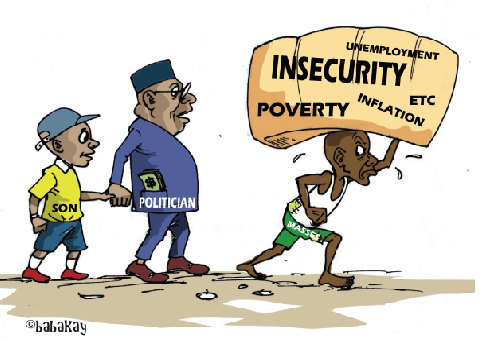

This, barewa ba ta yin gudu d’an ta yayi rarrafe (The antelope does not leap and expect its offspring to walk on its knees) is my suspicion with children of politicians and technoticians going into government themselves. In the 10th National Assembly (2023-27), at least 13 elected members of the House of Representatives are children of politicians. This does not include the hundreds employed as ministers, commissioners and special advisers and those crammed into CBN, NNPC, NDIC and across the federal and state civil service. If the parents treat Nigeria like the goose that lays golden eggs, will the children treat Nigeria any different?

We might not know for certain, but those who are doubtful have valid reasons to be suspicious considering how fragile Nigeria seems. In the story of the goose that laid one single golden egg a day, the owners, ecstatic at first, grew tired of one solitary golden egg a day and decided to kill and open it up to get the gold they believed was inside the goose. There was nothing.

Power By Any Means Necessary

There is a culture to securing and wielding power in Nigeria and most parts of the world that is destructive. Political parties and institutions have to be weak and being in power requires a certain ruthlessness that A Spell of Good Things captures hauntingly. In the story, the competition between two gubernatorial aspirants results in life altering consequences for two families and it is clear that young and impoverished people are considered no more than collateral damage in the quest for power. It will be tempting to dismiss this as fiction but the Gnassingbe dynasty in Togo and the recently toppled Bongo linage in Gabon, confirms that the antelope’s child does leap like its parent.

Refusing to link the nature and antecedents of politicians to their offspring in public office – elected, appointed and within government bureaucracies is telling about how some reason – or not. In the scorpion and the frog, Frog, agrees, against its better judgement to ferry Scorpion on its back across a river since Scorpion cannot swim. Frog is persuaded by Scorpion pointing out that it would be foolish for it to sting Frog since Scorpion will drown. Halfway through the crossing, Scorpion stings Frog. Why, Frog asks as it dies. Scorpion, also dying says: ‘I couldn’t resist the urge. It’s my character.’

The Fruit Does Not Fall Far From The Tree. Or Does It?

But sometimes the kid is watching the mother chew in order to eat a different way. This reality emerges in different ways within both books – but more clearly in The Middle Daughter where Nani has absorbed the ways of her father while her sister Ugo is comfortable with the choices of her mother; both are settled in the ‘rightness’ of their affiliations and the values that come with their alignments. In A Spell of Good Things, Eniola takes a different direction to his unemployed father’s self-pitying withdrawal from life and Adebayo does a skillful job of making the reader almost entirely empathetic to the difficult, yet rational choices Eniola makes with disastrous results.

We see this model of deviation from parental behavior with some of our next generation public servants. The children of men and women remembered with reverence sometimes chart a different course. They have learnt to cover up their spots with, to what seems to the third-party observer, a belief that their parents’ values have not served them well. Nigeria is a hard country to be impoverished and uninfluential in – besides, what is in a name if it cannot be traded?

In a world that is increasingly polarized by identity politics and algorithms that keep us in dulling echo chambers, culture and art – poetry, music, paintings, movies, documentaries and books provide ready mediums for engaging tough, complicated issues. The great ones are nondidactic allowing for flexible engagement with the content on one’s terms and as one wishes.

Adebayo and Unigwe are deft writers and I enjoyed both books even if I found one a little tedious to get through because I had too little sympathy for the main character. Another thought that haunts me from the books is Leo Tolstoy’s, ‘all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’. Which is not entirely true…but that’s another article.