It was the brilliant former First Lady of the United States of America, Michelle Obama who uttered this now famous statement during the 2016 U.S. elections — “When someone is cruel or acts like a bully, you don’t stoop to their level. No, our motto is: ‘When they go low, we go high’.” They have now become a slogan for exercising restraint in the face of intimidation and aggravation.

While the statement calls for caution in the face of intimidation and harassment, going high does not mean silence or sheepish behaviour; rather, it calls for a more mature and bold response that reflects the solution. These words on marble still resonate loudly in the halls of our collective conscience as Nigerian women – old or young, powerful or weak, rich or poor – battle an age-old scourge, the triple threats of sexual harassment, intimidation and misogyny.

The environment at home, work, play and even in parliament for women and girls continue to remain mostly hostile and discriminatory. Across generations, geography and gender, women are an endangered specie especially those who break ranks from the culture of silence and dare to speak out against these triple threats.

A 2018 Reuters Report ranks Nigeria as the 8th most dangerous place in the world to be a woman. This unsettling statistic should bother men and women of good conscience in our dear country.

A Woman’s Place is in the Senate Too.

The Nigerian political arena is very hostile to women. Women’s political participation has historically been limited, with various socio-cultural, economic, and institutional factors contributing to their underrepresentation in governance. Despite constituting nearly half of the population, women have struggled to secure significant political positions.

Several barriers impede women’s active involvement in politics including deep-seated patriarchal beliefs which often relegate women to subordinate roles; political campaigns requiring substantial financial resources, which many women lack due to economic disparities; the prevalence of violence, intimidation, misogyny and sexual harassment which discourage many and lack of internal party democracy where political parties often sideline female aspirants, favouring male candidates for elective positions.

Such is the case of Senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan, a Nigerian lawyer, social entrepreneur, and politician known for her resilience and commitment to public service particularly in her advocacy for the revitalization of the Ajaokuta Steel Mill. In the 2023 general elections, she contested and won the Kogi Central Senatorial seat under the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and now serves as one of only four female senators out of 109 in a largely male-dominated parliament.

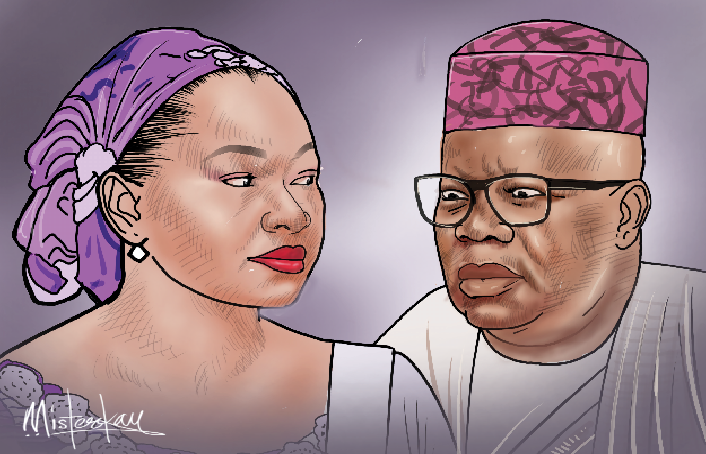

Once again, Senator Akpoti-Uduaghan dared to go higher and speak up against sexual harassment, intimidation and the culture of silence in a dispute within the Senate regarding seating arrangements, leading to a confrontation with Senate President Godswill Akpabio. She alleged that her reassignment to a different seat and subsequent actions taken against her were punitive measures resulting from her rejection of personal advances from the Senate President. These allegations have sparked discussions about conduct and ethics within the legislative body.

They have also ignited rage and criticisms from men and women who refuse to believe her, try to silence her, shame or blame her for her predicament. Victim blaming, stigmatisation and shaming are some of the key factors that prevent women and girls from speaking out when faced with sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence. This practice must stop.

For strong women like Senator Akpoti-Uduaghan, going higher means confronting systemic bias, intimidation and harassment rather than being silent and docile.

Federal Republic of Nigerian Men?

In 2019, only 3.4% of parliamentarians and 8% of ministers were women, ranking Nigeria at 149th and 124th respectively for these two metrics in the global standings. By 2023 these rankings had improved very slightly to 141st and 119th respectively. Currently, at the federal level, there are only four female Senators out of 109 (3.7%) and 16 out of 360 (4.4%) in the House of Representatives.

In the 2023 general elections, out of 15,307 candidates, only 1,552 were women, representing a mere 9.8% of the total. Ultimately, only 78 women were elected, accounting for just 5.2% of the successful candidates. This disparity is further highlighted in key positions where since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, no woman has been elected as president, vice president, or state governor.

At the subnational level women make up only 16.2% of commissioners across Nigeria. Across the regions, the lowest rate is in the Northwest (at 14%) and the highest in the North Central (at 29%). However, at state level, there are some positive cases, with Kwara state for example achieving gender parity with 50% of commissioners being women.

Within the State Houses of Assembly, however, women occupy just 50 out of 993 seats in state parliaments, with the highest number in the South south. Around 40% (15) of state assemblies do not have any women members, and some have not had a female legislator since the transition to democracy in 1999. At the local level, of the 370 LGAs with elected chairpersons, only 15 (4%) are women while 22 (7%) are caretaker chairpersons out of 318.

These alarming numbers beggars the question, is the Nigerian political space for men only? How can we blame women for the dismal numbers in elective and appointive positions and refuse to believe them when they call out intimidation and sexual harassment?

Where Women Dare to Tread

It appears every time a woman steps out in the Nigerian political space with voice, power and agency, she has broken ranks and incurred the wrath of misogynistic men and women who have been told to maintain the status quo. Sexual harassment within legislative bodies undermines the integrity of democratic institutions and perpetuates gender inequality. The recent allegations involving Senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan and Senate President Godswill Akpabio is a case in point.

Following her rejection of these advances, Akpoti-Uduaghan claims to have faced various forms of victimization within the Senate including being directed to move to a different seat during plenary sessions, a move she perceived as punitive. Her refusal to comply led to a heated exchange, with Akpabio ordering her removal from the chamber. She also alleges that Akpabio blocked her motions and attempted to malign her character as retaliation for her non-compliance.

These allegations have grave implications for women’s political participation, the broader issue of gender discrimination and have sparked a national dialogue on sexual exploitation, abuse and sexual harassment (SEAH). They also highlight the urgency for safeguarding measures and clear policies that protect female politicians from harassment, ensuring a conducive environment for their legislative duties. Addressing these claims transparently is crucial for upholding the Senate’s integrity and promoting a safe and equitable environment for women.

Society and the media should stop infantilizing, shaming and degrading women who speak up against entrenched misogyny. As the conscience of the people, the media should lead the call for an unbiased coverage of the situation and not allow itself to be used to wage a war against women in politics.

This is a watershed moment for the Nigerian Senate to lead by example and ensure that justice is served. Thank you, Senator Natasha Akpoti-Udughan, for speaking out, because “each time a woman stands up for herself, without knowing it possibly, without claiming it, she stands up for all women” – Maya Angelou.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel