With the world marking the 2025 World Day Against Child Labour recently, the global community must confront an uncomfortable truth: child labour remains a persistent stain on the conscience of our civilisation.

With an estimated 138 million children engaged in labour globally, 54 million of them in hazardous work, the goal of eliminating child labour by 2025, as once envisioned by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), has sadly not been achieved.

Like many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria bears a disproportionate share of this burden.

According to the Nigeria Child Labour Survey Report (2022), over 25 million Nigerian children, or nearly 40 per cent of those aged 5 to 17, are engaged in one form of child labour or another.

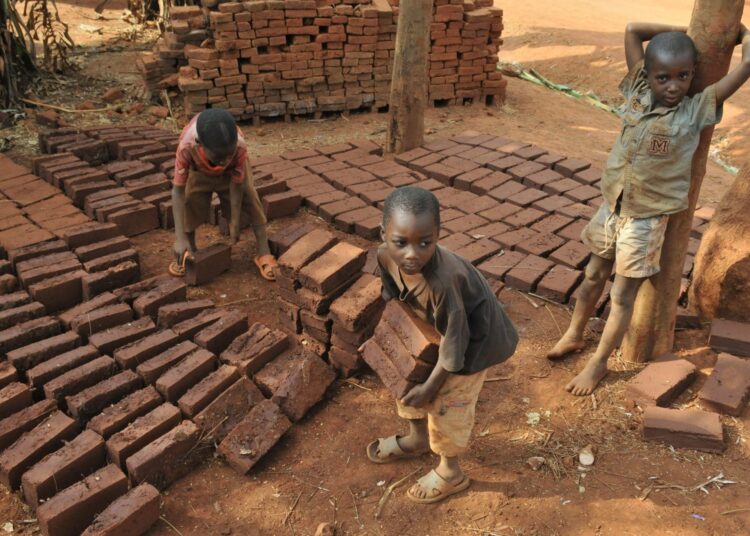

In rural areas, the figure is even more harrowing: 44.8 per cent. Behind each of these statistics is a life interrupted – a child who should be in school but is instead carrying bricks, hawking goods in traffic, or working in a mine or on a farm.

This year’s theme, “Let’s Speed Up Efforts!”, is both a rallying cry and an indictment of the slow pace of progress. The truth is that while modest gains have been made globally, with a reduction of 22 million child labourers since 2020, we remain far from where we ought to be. And nowhere is the urgency greater than in Nigeria.

While the federal government has taken commendable steps, including participation in the ILO’s Accelerating Action for the Elimination of Child Labour in Africa (ACCEL Africa) Project, more needs to be done.

The sheer scale of the problem demands a multi-pronged national response that is better funded, better coordinated, and driven by both moral conviction and political will.

We acknowledge recent statements by Minister of Labour and Employment Mohammad Dingyadi affirming Nigeria’s status as a Pathfinder Country under the ILO framework. The minister cited ongoing reviews of national legislation, community programmes, and rescue operations.

In the considered opinion of this newspaper, while these are steps in the right direction, enforcement remains a major stumbling block. Reports show that Nigeria lacks the necessary number of labour inspectors and suffers from inadequate funding for regulatory bodies.

Additionally, legal protections for working children remain inconsistent, particularly for those in the informal economy or self-employed, leaving millions outside the scope of formal protection.

The role of state governments in this fight cannot be overstated. Though passed at the federal level, the Child Rights Act remains unimplemented in several states, undermining national cohesion in tackling the menace.

The message from Nigeria’s First Lady, Senator Remi Tinubu encapsulated the moral imperative of this fight: “It is unacceptable that children are still forced to work instead of going to school, pursuing their dreams, and learning how to grow into productive members of society.”

Her call to invest in education, support families, and strengthen laws must not go unheeded.

Equally powerful was the statement from FIDA Nigeria, which forcefully reminded the nation that child labour is not a cultural tradition or survival strategy but a form of violence, neglect, and exploitation of children. FIDA’s call for justice, coordinated law enforcement, massive community sensitisation, and full accountability must be met with more than applause. It must be met with action.

We also commend the Paediatric Association of Nigeria (PAN) for bringing a public health perspective to this issue. As physicians caring for Nigeria’s children, their reminder that child labour undermines a child’s mental, physical, and emotional development must serve as a wake-up call. Child labour is not merely a social or legal issue; it is a national emergency affecting health, education, and future productivity.

In tackling this crisis, we must not lose sight of the root causes: poverty, unemployment, weak law enforcement, lack of access to education, and cultural practices that normalise child exploitation.

Addressing child labour, therefore, demands economic intervention, social protection, and a reorientation of societal values. Universal child benefits, as proposed by UNICEF and ILO, would go a long way toward easing the economic pressures that drive families to depend on children for income.

At the same time, we must empower youth, who represent 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population, to be champions for change. Young people must be armed with the tools, knowledge, and civic courage to advocate for their peers and resist societal norms that perpetuate child exploitation.

Finally, we urge every Nigerian — leaders, employers, civil society actors, faith-based institutions, and ordinary citizens — to treat the fight against child labour not as a seasonal campaign but as a daily moral duty. Every time we patronise street hawkers who should be in school, every time we ignore a child in domestic servitude, we become complicit in this grave injustice.

As a newspaper, we affirm our commitment to amplifying the voices of the voiceless and holding those in power accountable for protecting our nation’s most vulnerable citizens. Let this year’s World Day Against Child Labour not be another day of empty promises. Let it be the day Nigeria takes an essential step toward catering to the needs of our children. Let us rise as one to protect, educate, and empower every Nigerian child.