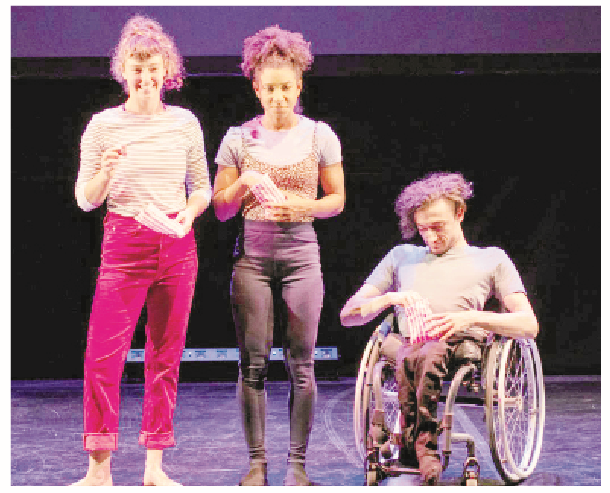

From Africa to Asia to Europe and the Americas, the inclusion of Persons With Disabilities (PWDs) seems to be a new concept. In the past, the performing arts in most countries were divided into two: mainstream theatre where able-bodied artistes perform for able-bodied audience, and the second, the theatre for the disabled, where able-bodied artistes or the disabled, perform for a disabled audience.

In recent years however, performing artistes, networks such as the International Inclusive Arts Network (IIAN), International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts (IETM), and a few governments are mindfully seeking ways to ensure the inclusion of PWDs or Persons With Different Abilities as they are preferable called, in mainstream performances.

At the ABITFA IIAN-led Seminar on Inclusivity In Performing Arts, featuring IIAN Country Representatives, Aamir Nawaz (Pakistan), Ginny Manning (UK), IIAN Vice President, Vicky Ireland, and Pamela Udoka, ASSITEJ International, Vice President, lead speaker at the seminar, Jaume Bello of Cia La Maxima, Spain, said there are always ways to representing different-abled persons on stage.

Bello whose organization since 2013 began working on the inclusion of different-abled persons in the performing arts space in Spain, said the institution currently have jobs for them, and employ artistes of different abilities.

Through its personal-centered-care which caters to the 4Ps: People, Process, Product and the Public, Cia La Maxima works with different-abled persons through all the processes for making a show.

Emphasis, he said, is laid on their areas of strength, and increasing their skills/capacities in those areas (for artistes who argue that different-abled persons lack theatrical skills), so that they all “feel important but not special.”

“Those with reading skills are supported to read poems before the audience. Some are supported to work in the costume department for performing groups. Different-abled persons can take part in a show based on their abilities, with opportunities to improve their involvement as they learn. Even those with more enhanced fragility can be employed at their capacity (like painting props for productions). We also take them to tours to Puppetry museums to show them how puppets are made before starting production processes for a puppet performance.

“We deploy a demonstrative learning or training approach to building capacity. Every one of them is assigned a responsibility of what to do in a show or exhibition. And we organize familiarization workshops of how the company works for high schools and tertiary institutions,” said Bello.

However, on issues beyond the control of performing arts groups, such as ensuring that different-abled persons own their narratives, fears of them being bullied, and the cooperation between the academia and performing arts practitioners to enhance inclusion of different-abled persons in the performing arts, Bello acknowledged as “a slow process that demands much support.”

“At Cia La Maxima, the narrative of a show is chosen by the artiste(s). But we also try to work with the artistes to clarify the objective of the script/narrative, if they seem not to pass the right information about different-abled persons to the audience.

“There is a real fear by family members vand organizations, of different-abled persons being mocked onstage or taken advantage of. This is a result of the fact that societies, for the most part, do not respect or treat them well. This had been the case in Spain some 30 years ago,” said Bello who have had to fight with institutions for different-abled persons he had worked with over the years on matters of social impact.

“But it is a fight we must take head-on, otherwise the situation will not change,” he said.

On the collaboration between the academia and performing arts practitioners to ensure the inclusion of different-abled persons, Bello said Cia La Maxima is working towards the improving skills of its different-abled persons in order to get them into the Academy of Arts School. “But it is a slow process that requires lots of support.”

Buttressing Bello’s point, Nawaz said chairing Pakistan’s IIAN office, has seen some changes in the nation’s performing arts space.

“A few theatre companies are starting to bring (different-abled persons) onto the mainstream performing companies. This is good because it helps them to have a job and make a living.

“However, we are still looking for a way forward like teaching new entrants into the concept how to include different-abled persons in the performing space, and for the government to provide inclusivity funding,” he said.

There is also the challenge of architectural barriers, and set/stage designs that exclude different-abled persons in most countries.

For Vicky Ireland, artistes shouldn’t wait for politicians to take action. “It is down to individuals to make things happen.”

“Creativity gives us ideas of alternative means to achieve inclusion in the performing arts (with or without government),” said UK-born Jamaican actress and psychotherapist, Makeda Solomon, whose native country Jamaican lacks funding for inclusivity.