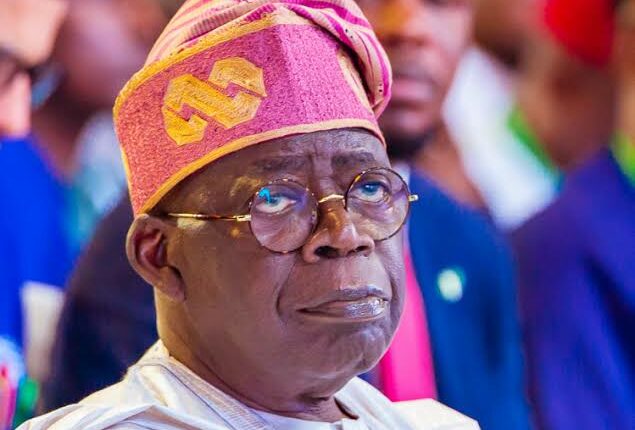

Recently, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu signed into law the Northwest Development Commission (NWDC) and Southeast Development Commission (SEDC) bills into law bringing the total number of regional commissions to four.

Additionally, the National Assembly has passed for third reading a bill to create the North Central Development Commission, sponsored by senators from Benue, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, Kwara, and Kogi states.

Barring any last-minute changes, the North Central Development Commission bill is expected to pass and be signed into law by President Tinubu. Following this, the South West Development Commission bill, which is at an advanced stage in the legislative chamber will likely be next. This would result in each of Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones having a development commission.

As of today, Nigeria has four regional development commissions: the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), Northeast Development Commission (NEDC), Northwest Development Commission (NWDC), and Southeast Development Commission (SEDC). While the NDDC and NEDC are operational, the NWDC and SEDC will commence operations once the government finalizes the required modalities relating to the appointment of boards and funding sources.

We are persuaded by this development to ask what tangible changes will Nigerians see beyond increased bureaucracy now that the regions have a development commission for themselves.

Following the establishment of the NDDC and NEDC, there were calls for the creation of such commissions in the other zones. Lawmakers argued that these commissions would expedite the rebuilding of homes and economies in regions under persistent attacks by criminals and bandits.

The requests for regional commissions are rooted in the need to address unique development challenges across the country. Each region has its specific issues and needs. For instance, proponents of the SEDC argue that the commission will manage funds from the federation account for reconstructing and rehabilitating roads, houses, and other infrastructure damaged due to the civil war. The commission will also address ecological and environmental challenges in Southeast states of Abia, Imo, Enugu, Anambra, and Ebonyi.

The Igbo socio-cultural group, Ohanaeze, is of the view that the SEDC will tackle insecurity aggravated by the Biafra agitation, and post-civil war challenges, as well as address infrastructural decay in the region.

Similarly, the APC senators’ forum supports the North Central Development Commission, asserting it will address the region’s security challenges and help it realize its full potential.

However, there is no solid basis for the proliferation of regional commissions. While the reasons for their establishment may seem plausible, they highlight contradictions in the nation’s governance. On one hand, there is a call for downsizing ministries, departments, and agencies, while on the other hand, there is agitation for creating more bureaucracies.

It is alarming that despite the government receiving the Stephen Orosanye committee report on restructuring and rationalizing parastatals, commissions, and agencies—a report that recommended mergers and scrapping of some agencies—we are now advocating for more regional commissions.

Only four months ago, specifically in March, the government inaugurated a committee for the implementation of the Oronsaye Report following assurances from the president that parts of the recommendations of the report would be implemented.

Secretary to the Government of the Federation (SGF), George Akume, while inaugurating the Committee on behalf of President Bola Tinubu said the “implementation would involve the merger, relocation, subsuming or scrapping of some parastatals, agencies, and commissions aimed at reducing the cost of governance and streamlining efficiency across the governance value chain,”

It is a clear contradiction that a government that inaugurated a committee to present white paper on merger and scrapping of agencies is busy giving its nod to the establishment of new ones.

Given the nation’s serious revenue challenges and the call for reducing governance costs, creating more commissions, which will likely become financial burdens, is counterproductive.

We hold the notion that the agitation for more regional development commissions is misplaced, lacking concrete basis, self-serving, and unlikely to produce tangible results other than increasing bureaucracy and opportunities for corruption.

Essentially, the existing ministries, departments and agencies, if managed effectively and insulated from unethical practices, can address the key development challenges that fuel the demand for regional development commissions. The task is to manage them well, not create new ones.

Current regional commissions, such as the NDDC and NEDC, already engage in infrastructure projects, education, and youth economic empowerment. These activities can be managed by existing agencies if properly overseen.

It is difficult to understand why lawmakers and President Tinubu did not consider restructuring existing agencies to make them more effective instead of creating new development commissions.