The desire of those who manipulate elections is to enjoy the ‘fruits of electoral legitimacy without running the risk of democratic uncertainty.’ (Schedler, 2002).

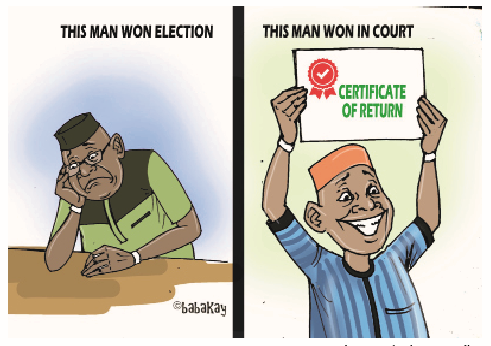

Accusations of election rigging are not new – that is why there are various geographic versions of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somzo’s, ‘Indeed, you won the elections, but I won the count’.

The recently concluded off cycle elections in Imo, Bayelsa and Kogi are not any different and there were no surprises for those who study elections – the parties in government house remained in government house. Nigerian elections are increasingly being decided by a small group of people in the judiciary as contestation of election processes and results rise. Candidates, their supporters and those with a stake in a healthy democracy are reluctant to accept results due to the conduct of elections and the opacity around collation of results.

At the rate of contestation, there could be a need to prepare for a time when judgements will no longer be sufficient to grant the fig leaf of legitimacy especially with the growing perception that judgements are procured and/or that only those with near limitless amounts of cash can navigate the costs of the election tribunal process. Asides millions to lawyers in fees, getting evidence from INEC and securing the certified true copies of judgements required to file appeals have also become something only those with cash to burn can afford. Some might say the SDP gubernatorial candidate for Kogi is wise to eschew the invitation to ‘go to court’ but that he is forced to make that decision due to the knowledge that he is unlikely to get justice should be extremely sad and troubling for those with long term vision…or maybe sorrow is only for idealists and dreamers.

Like the 2023 general elections, there are different views about the quality of these just concluded off cycle elections and whether our elections are improving or not. This is a bit worrying – should there be contention about whether an election process is improving or not? Should it not be fairly agreeable what constitutes an election with integrity and from our history of elections should we not have measurable ways of determining if the conduct of elections has improved? Maybe part of the challenge is agreeing on the qualitative and quantitative metrics for assessing elections. Some might argue that there will always be divergence and that those who do not win elections will always cry foul but this type of uncertainty about indicators of improvement while acceptable amongst the general public should not be the case within civil society particularly those who work on elections.

Yardstick of ‘bad elections’

2007 is often held up as the worst elections Nigeria has had since the start of the 4th Republic but one cannot help wondering if late President’ Yar’Adua’s acceptance that the elections that brought him into power were flawed had anything to do with this general acceptance. If he had insisted that the elections were fine because they compared favorably with general elections in 1965 or the 1966 elections in the then Western Region which resulted in hundreds killed, would we have the 2007 benchmark? The 2019 and 2023 elections were worse than the 2015 elections. For one, discounting for inflation, they cost a lot more and delivered less than was expected particularly with the introduction of technology – INEC Result Viewing (IReV) portal and Bi-Modal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) in the elections early this year. If we use the number of election tribunal cases as a yardstick, in 2007 86.35% of all offices contested ended in court. In 2011, it dropped to a little over 51% and in 2015 it dropped to 43%. By 2019, the cases rose to 51% and it is anyone’s guess what the percentage is for 2023 as the cases are still ongoing and the new mantra is ‘go to court’. Lucky election lawyers and judges, one would think INEC works for them.

Two, collation of results has remained a black hole that has not been solved. The collation of results for the 2019 Rivers State gubernatorial elections ended up in a stand-off between Amaechi and Wike’s armies – it was almost a month before INEC could announce results in favour of the incumbent. Three, these elections are worse because INEC is more compromised – with the slew of partisan RECs and employees, conflicting statements about the use of technology to ensure transparency of results transmission and the rise in ‘cancelled votes’, – which is why more elections are ending up in court. And fourth, while the judiciary does not conduct elections…they embolden those who compromise pre and post-election processes with the conflicting judgements they give on everything from when pre-election issues affect election results and how judge math can result in the candidate who came fourth being the Supreme Court’s governor.

The situation is not helped when experts cannot agree on whether our elections are improving. Some want to use the number of people killed as a measure, or the voter turnout (which arguably is influenced by violence and rigging) or the seats won or lost by incumbent parties (that the judiciary is steadily overturning), others want to use the independence of INEC and the RECs and the commitment to the use of expensive technology tax payers paid for to make results collation more transparent.

A framework for assessing elections

The subjectivity in assessing elections might be helped with a framework such as Andreas Schedler’s seven conditions required for elections to fulfill the promise of effective democratic choice as outlined in The Menu of Manipulation (Journal of Democracy Volume 13, No.2 April 2002).

The first is Empowerment i.e., voters can wield their vote freely without fear and intimidation and their ability to vote is not restricted. The second condition is Free Supply which refers to citizens being free to form, join and support parties, candidates and policies of their choice. Restrictions on party registration, candidate registration with INEC etc. is part of what determines success under this condition. Free Demand speaks to the ability of citizens to learn about available alternatives through access to diverse sources of information with no restriction on political and civil liberties. In the fourth condition, Inclusion, citizens have equal rights of participation and representation and there can be no legal, pseudo-legal restrictions on the ability to campaign, participate and vote. This speaks to the use of incumbent state power to restrict movement, deploy state security services against opponents, impromptu public holidays and other tricks we have experienced over the years – what some like to call in Orwellian speak, ‘the beauty of democracy’. A fifth condition is Insulation where citizens must be free to express their electoral preferences and not be coerced or intimidated, the sixth is Integrity of the election process, rules and execution that must deliver one person, one vote and the seventh is Irreversibility which speaks to elections having consequences from elected officers taking office peacefully, to the use of the judiciary to change the import of how voters cast their ballots.

Schendler’s framework is by no means perfect and the conditions are not fool proof nor easy to measure. For instance, there were reports of voters prevented from casting their ballots during the general elections but it is not known how widely this happened and without the numbers, it becomes difficult to assess the empowerment condition. There is something to be said for those who say only by counting can institutions such as INEC be truly responsible, however not all things that can be counted, count. To safe guard the legitimacy of our review of elections, Nigerian civil society needs to design and agree a framework for assessing elections that balances what can be counted and what must be measured – hard but necessary work. As Nigerians trust in elections wanes, civil society should get more creative about how to move from subjective to objective assessment of elections.