It’s a most unlikely crime scene. I travelled by road from the Benin airport to Uromi, Esanland’s most significant town, for a wedding about three years ago.

The fear of kidnappers is a constant worry for road users. I was nervous for nearly four hours of the taxi ride, especially as we turned off the busy Agbor Road and veered onto narrow, lonely roads meandering through many forested small towns and villages.

I was nervous. When the driver ran into a pothole, and a loud noise suggested we might have lost a wheel or something, I insisted he should keep moving, as long as the car could still move, until we later discovered it was the wheel cover.

Entering Uromi

It was not until we passed Ubiaja, the hotspot between Biafran and Federal troops during Nigeria’s civil war and cultural capital of Esanland, and reached Igueben, the rusty town of one of Nigeria’s famous politicians, Tom Ikimi, about 20 minutes’ drive from Uromi, that I started breathing easy. It was my first visit to Uromi, a town I had known and heard about since my teenage years.

Memories from the past

My earliest memory of this town was when my mother worked as a cook at St. Theresa’s Hospital, Kirikiri Ajegunle, Lagos, owned at the time by Dr. Okoli, an Igbo man, and his wife, a nurse and an Esan from Uromi. Occasionally, when there was some social event in Uromi, the Okolis took my mum along to cook, and she returned with plenty of palm oil, large tubers of yam, and fresh fruits.

But there’s another memory of Uromi apart from my mother’s work and travels. It’s the historical significance of this town in the old Benin Empire. More contemporary references might be about the exploits of some of Uromi’s notable people, such as the three Anthonys – Enahoro, Olubunmi-Okogie and Anenih – whose footprints in politics and liberation theology cannot be easily forgotten.

Innocence lost to rage

Yet, these notable persons were inspired by the town’s extraordinary heritage of struggle and resistance to oppression. Uromi resisted the expansionism of the Benin Empire during Oba Ozolua’s reign and fought the British colonial invaders.

Though many of the town’s original settlers are believed to have come from central Nigeria, migrants from other places also settled there, highlighting its tolerance for visitors and diverse heritage as the town grew into one of Esanland’s most important agricultural trading posts.

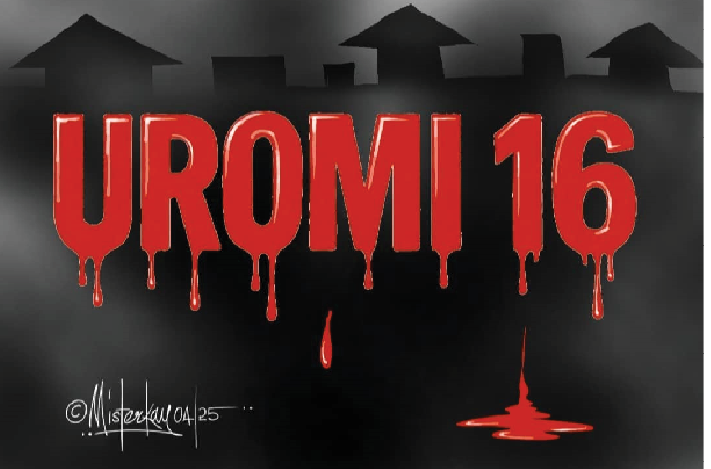

That diversity, enterprise and welcoming spirit now seem like a story from a bygone era. After the tragic killing of the 16 travellers reportedly going to Kano to observe the Eid on March 28, the town has lost its innocence. For a long time, it will be remembered not as that place my mother frequented as a cook or the homestead of Enahoro, one of Nigeria’s greatest patriots and nationalists, but as a crime scene.

Agony of bereavement

The heartbreaking story of Hauwa Bala (whose husband, Isah, was among the Uromi 16) who went into premature labour upon hearing of her husband’s tragic death or Sadiya Sa’adu, who lost a brother and a nephew will haunt the community, as will the stories of each of the dead, and indeed the unfolding horror in Uromi now under siege and a brutal crackdown. The security services are poised to forget their complicity and instead crush the town in a mocking search for justice.

Journey to anomie

How did we get here? Kidnapping and banditry have grown from a fringe business to a N2.23 trillion naira industry, and hardly any part of the country is spared this misery. In the last 10 years, clashes among rival cult gangs have been rife in Edo State, as have been reports of severe violence as a result of farmer-herder clashes. One report said in 2020, Edo was the third most affected by violence in the Niger Delta after Delta and Rivers States.

Violent clashes between farmers and herders have led to significant loss of lives. In February alone, 27 farmers in Edo were reportedly killed by herdsmen. This figure is only a tiny part of the bloody trail that often includes grotesque stories of rape, murder and wantonness wrecking many farming communities across the country as herders roam southwards for pasture.

Politicians’ fake outrage

While the affected communities writhe in anguish, official response, especially by politicians and the police, has ranged from chewing the microphone with empty promises of justice to sheer indifference and, in fact, alleged complicity in supplying weapons to the herders in some cases. We’ve seen this repeatedly across the country, from Uromi in Edo to towns in Benue and Plateau States.

When the state, expected to guarantee security and maintain law and order, abdicates its responsibility, turns a blind eye or becomes complicit, people take the law into their own hands. What happened in Uromi on March 28 is one of the tragic outcomes.

The appearance of shock and outrage amongst politicians and the security services is hypocrisy disguised as empathy. They can fool themselves all day long. Unless they begin to rebuild trust in communities and people – whether farmers or herders – can see that there are consequences for breaking the law, Uromi will not be the last tragic crime scene.

Citizens’ dilemma

Yet, while many communities are under attack, residents are on their own. The Supreme Court recently gave a judgment upholding the death sentence on Citizen Sunday Jackson and criminalising self-defence even in the face of a clear threat to life. The judgment is an absurdity that compounds the dilemma of communities coping with security services often unwilling, unable or unavailable to protect citizens.

If unarmed Jackson had known that self-defence against herdsman Boua Bururo, who stabbed him seven times on his farm, would not avail him, that if he didn’t die by his attacker’s knife, he would have still been killed by the law, he might have surrendered to his attacker. What a fate!

What kind of society gives the victims the short end of the stick? If communities cannot trust that the police can defend them and courts will not provide justice, self-help prevails. As things stand, respect for life and private property rights is endangered, and to pretend otherwise is to enable jungle justice further.

No excuses

What happened to the Uromi 16 stands condemned, but sadly, the fake outrage by politicians obscures the history behind the tragedy. It neither guarantees that a proper investigation will be done and the perpetrators brought to justice, nor does it assuage current tensions and paranoia in many communities across the country.

Open, unrestrained must stop. The Federal Government must also fast-track community/state policing, which will hopefully use modern surveillance tools and techniques to prevent and fight crime. The current security system is unfit for purpose.

Burden of kindness

I’m sorry for the truck driver who, after driving past the stranded passengers early on, turned back nearly two kilometres to pick up the Uromi 16 and other stranded passengers from the roadside. Even though he escaped the mob attack in Uromi, he now lives with the guilt of a bloody reward for his act of kindness, the tragic consequence of a society where trust and compassion have declined.

Neither the Uromi I read about in history nor the one my mother visited is the same as the present crime scene. Something is broken, and false outrage won’t fix it.