I got this question a lot as family, friends and colleagues found out about the breast cancer diagnosis. I had no convincing answer. Even to myself. It was left to be in a country where I had no social structures at a time like this.

I did look to the familiar for a biopsy. School, work, love, conferences and life in general made the UK and US more logical choices for me. I asked trusted friends for help arranging a biopsy so I could be efficient. While I waited, work sent me to Berlin – my first visit ever to Germany. Germany’s medical care is legendary and so I thought, ‘why not?’

After meetings in Berlin, I left for a clinic in Wiesbaden, a small town outside Frankfurt popular with Nigerians with ties to Julius Berger. Exactly one week after the sample was taken, I got the result: triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), fast growing aggressive cells. If breast cancer is a western, TNBC is the baddest villain, but I did not know that then. Who even knew there are types of breast cancer? There are some things we never want to have to know.

Within 10 days, I was back in Wiesbaden for the next important step – staging. For this I needed a Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan that would determine what stage the cancer was in, which would in turn determine treatment. The PET scan produces detailed three-dimensional images inside the body by detecting radiation given off by a radiotracer – a dye of sorts injected into your veins (or inhaled/ingested) which helps doctors determine cancerous cells because these mutated cells use up glucose at a faster rate than normal cells. Nigeria got its first PET scan machine only in 2022, thanks not to the investment of any federal or state government, but a private oncology centre in Lagos. How have our oncologists been determining cancer staging and treatment without this machine?

Shivering under the blanket thoughtfully provided by the hospital as I waited for the tracer dyes to diffuse through my body, I wondered: cold or nerves? I slept through it, out for the entire process immediately I stretched out on the machine.

The good news was: cancer was at stage 2 and had not spread and TNBC responds well to chemotherapy. The recommended treatment plan was 16 rounds of chemo, then a lumpectomy to remove the tumor, and then 5-6 weeks of radiation. Bad news: I had to move fast, travel was not recommended (presuming I was an heiress with a private jet and could fly in and out for chemo) because of how miserably sick chemo makes the body and weakens the immune system. Buying the drugs and getting them administered at home was also not advisable though it was a possibility. Keeping track of the white blood cells count, ensuring organs are coping, this was where care could slip. Could I start right away?

Of course not.

Abuja – Dakar – New York – Wiesbaden.

Tell family. Tell colleagues. Tell bosses. Then I was ready. Sort of.

Factors influencing decisions

No one in my family had a valid EU visa at this time. Germany was alien, the language and people unknown. There was no one to call, to say ‘check on her’ or ‘make pepper soup and take to her’ (that was soon sorted out!). But the advice to get started without delay gave Germany an advantage despite the well-meaning pressure to consider the US or UK. I had introductions to experts in TBNC across the world within hours – all standing by and ready to assist.

But two things helped me feel more comfortable with Germany. One, if I moved, the doctors would want to do these tests all over again…I did not feel I had the time, energy or money.

Second was health insurance. Until it kicked in (it never did; thankfully the organization I work for was supportive), I would be paying out of pocket and US medical costs were easily 4-5x higher than Germany. So, Germany it was.

The seeds of Germany’s health care system were sown on the eve of the carving up of Africa, with Bismarck’s 1883 Health Insurance Act. It was the first social health insurance system in the world. Today, Germany boasts of being within the top 20 health systems in the world spending 11% of GDP on health expenditure (€407 billion in 2019 or almost €5000 per person). Government funds 77% and the rest is private funded and everyone is covered. Everyone. Including refugees.

In addition to government funding, employees & employers fund up to 14.6% of gross wages, shared equally by the employer and employees and at the point of access a copay (this is where a patient is required to pay part of the cost) is required in some cases but not for preventative services such as cancer screening. Policy makers understand that prevention is better than cure and want zero excuses for those who need regular checkups. Germans who earn below a certain amount are compulsorily covered (88%) and private health insurance exists for high earners (11%).

The unemployed pay a proportion of their unemployment entitlements and for the long-term unemployed, government contributes for them. The German federal government is not directly involved in care delivery but uses laws and regulation to set quality measures and ensure that providers cannot arbitrarily increase premiums and copayments. Dependents and children are covered free of charge and special schemes exist for the police, military and other public service employees.

Health funding in Nigeria

In Nigeria – the federal health budget covers part of the funding required for health insurance under new National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) law enacted in 2022. The idea of a health fund is to act in a similar way as our pensions do – i.e., contributions from employees, employers, government (e.g., N4.4 billion was allocated to NHIA to cover retired military) and investments. Just like arrangements must be made for those who will retire, arrangements have to be made for those who will inevitably need medical care. It is not clear though, at least not from the agency’s website, how much the NHIA has in funds, what it spends annually, what it generates and who has access.

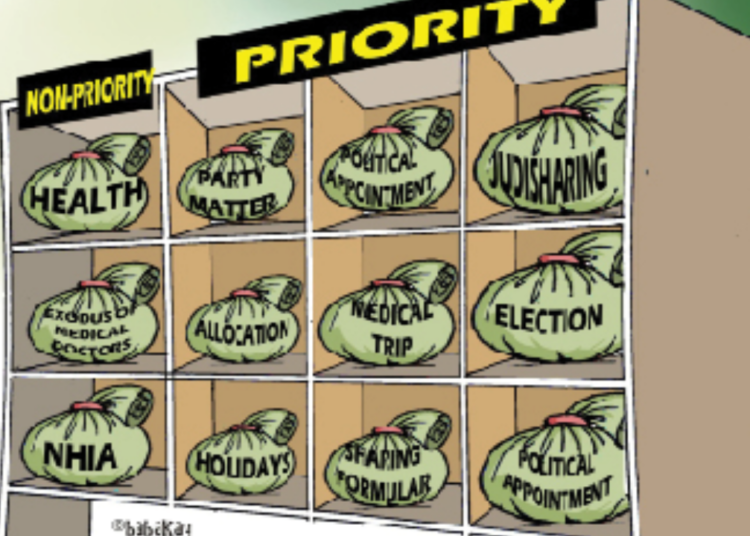

Health has never been a priority for Nigerian government and policy makers. For the first time since the Abuja Declaration of 2001 where Africa Union members pledged to dedicate at least 15 percent of annual budgets to health, Nigeria’s 2023 health budget got as high as 5 percent of the budget. High recurrent expenditure and corruption ensure that there is always too little to invest in building our medical facilities and expertise.

This is why Nigerians have to migrate when they are ill, increasing the financial and emotional resources required to get better. India, Turkey, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Ghana etc. have become havens for Nigerian patients. Several factors dictate where patients go for health care outside Nigeria: family, budget, medical referrals, visas and expediency. Improving the health sector requires detailed research and assessment of medical tourism needs and costs in order to prioritize government interventions – until then, Nigerians will continue to seek better health care wherever they can.

October is breast cancer awareness month: get checked, donate, advocate.

* This article was first published in 2020.