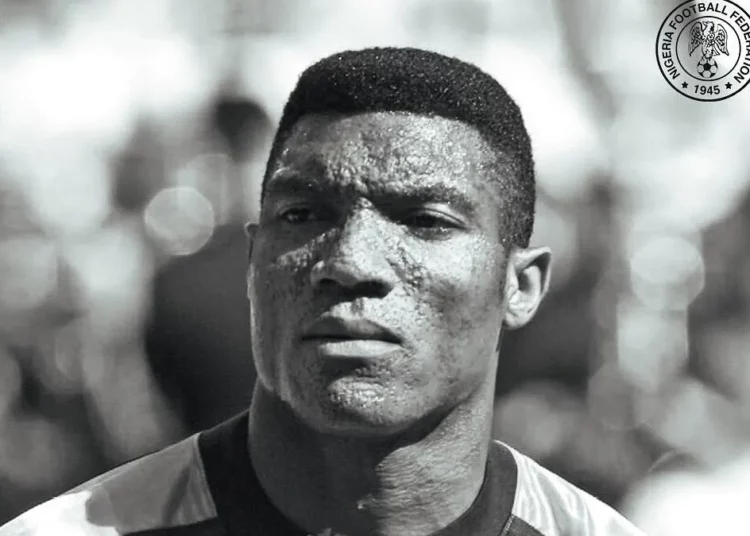

In the pantheon of Nigerian football greats, legendary Super Eagles goalkeeper Peter Rufai stands as a dazzling anomaly—at once a trailblazer and a showman, a leader and a servant of the game. His death at 61 has stirred a wave of heartfelt tributes, but mere nostalgia cannot fully capture the legacy of a man who redefined goalkeeping not just as a function, but as a performance art.

Known as Dodo Mayana by fans, Rufai was more than safe hands behind Nigeria’s golden generation—he was the pulse, the anchor, and often, the margin between defeat and glory. In the iconic 1994 Africa Cup of Nations final, his reflexes denied Zambia’s best efforts just as decisively as Emmanuel Amuneke’s goals sealed victory. At the nation’s first-ever World Cup appearance that same year, it was Rufai who wore the captain’s armband and carried the weight of millions on his gloves, helping to propel the Super Eagles into global consciousness.

And yet, all of it—the saves, the swagger, the superlatives—was born of serendipity. Rufai’s journey into goalkeeping wasn’t preordained. It began, quite literally, when a teammate walked off the pitch mid-game and young Peter stepped in. That moment of improvisation became the turning point not just of a career, but of Nigerian sports history.

Born into royalty in Lagos and raised partly in Kaduna and Port Harcourt, Rufai’s childhood was marked by mobility and improvisation—traits that would later serve him between the goalposts. His life, like his career, bore the marks of quiet resilience: a name change to avoid ethnic reprisals during the civil war, a solitary journey to Lagos to chase football dreams in Christmas shoes, and countless hours between the sticks perfecting a craft that demanded as much courage as talent.

By 17, he was playing in national cup finals. By 18, he was holding off some of the continent’s best attackers. And by his early 20s, he was Nigeria’s first goalkeeper to break the barrier into professional European football. These milestones are worth revisiting not just because they are impressive, but because they defied every structural and societal limitation facing a young African athlete in that era.

What made Rufai even more remarkable was the balance he maintained between flair and discipline. Nigerian football is no stranger to flamboyant personalities, but Rufai’s eccentricity never overshadowed his professionalism.

He juggled the ball with confidence, styled his hair with punk defiance, but was never anything less than the team’s spine when it mattered most.

His post-playing years were just as instructive. While many chose the limelight of commentary booths or the corridors of football politics, Rufai retreated into the quieter work of nation-building. He established football academies, mentored aspiring players, and gave his time freely to the youth he once was. He turned down a royal crown to stay true to his football calling—a gesture that speaks volumes about the man’s sense of purpose.

In a country desperately in need of heroes who serve beyond their peak, Rufai showed what it meant to give back with humility. He didn’t just enjoy his prime; he invested it into the dreams of others. The ripple effects of his mentorship are likely still unfolding across Nigeria’s sports landscape.

It is fitting that the Nigeria Football Federation and President Bola Tinubu have acknowledged Rufai not merely as a former international, but as a national treasure. Tinubu’s words were apt: “Peter Rufai will be remembered as one of those patriotic sportsmen who wrote their names in gold.” For once, political tribute matches public sentiment.

Yet Rufai’s death also prompts a moment of national introspection. The passing of another member of the golden 1994 squad—following Rashidi Yekini, Stephen Keshi, Uche Okafor, Tom Oliha, and Wilfred Agbonavbare—should compel a conversation about the welfare of ex-internationals. Too many of Nigeria’s football heroes age into neglect, ill health, or obscurity. Rufai’s death, reportedly following a period of illness, reminds us of the frailty behind the fame.

Nigeria has no shortage of talent. What it has often lacked is a system that nurtures, celebrates, and supports that talent sustainably.

Rufai did his part. He inspired, he mentored, he represented. The challenge now is whether the institutions he served—football, government, civil society—will honour his legacy with more than ceremonial platitudes.

In the considered opinion of this newspaper, there should be a national youth goalkeeping program in his name .A fitting memorial must ensure that generations to come know not just the story of “Dodomayana,” but also the values he embodied: discipline, self-belief, and national service.

In the end, Rufai’s legacy is not merely that he was the best at what he did. It’s that he made Nigerians believe. In the face of uncertainty, he stood calm. In moments of chaos, he flew—literally and metaphorically. He made a whole generation of children believe that goalkeepers weren’t just the guys who wore gloves—they were heroes in their own right.