Painful personal stories have revealed the devastating consequences of genotype misdiagnosis, leaving many families raising children with sickle cell disease (SCD) despite believing they had taken the right precautions before marriage.

One of such case is that of Mrs. Agbo, a mother of three in Dagbana, Abuja, who recounted how she and her husband were declared genotype-compatible before marriage. Years later, they discovered their last child was SS.

“We did the genotype test as requested by the church. My result showed AA and my husband’s AS. We thought we were safe. But our third child fell ill repeatedly, and after several tests, we were told she is SS. We were misdiagnosed, and now we are left to deal with the consequences,” she lamented.

Another victim, Mrs. Mary Ukaibe at Nyanya, in Abuja shared a similar ordeal. She was initially certified AA but later discovered she was AS. “Luckily, my husband is AA. But imagine if he were also AS, we could have unknowingly had children with sickle cell. It’s frightening,” she said.

According to the Association of Medical Laboratory Scientists of Nigeria (AMLSN), the surge in genotype misdiagnosis is largely fueled by quackery, fake reagents, and poorly regulated laboratories.

AMLSN President, Dr. Casmir Ifeanyi, warned that many couples are misled into believing they are genotype-compatible, only to later discover otherwise after giving birth to children with SCD.

“Misdiagnosis occasioned by quacks and substandard reagents is contributing significantly to the rising number of sickle cell births in Nigeria. This problem cuts across both public and private laboratories, worsened by uncalibrated equipment and weak oversight,” he told LEADERSHIP.

He revealed that even professionals risk being deceived by fake products flooding the market. “If I, with my knowledge, could almost be misled, imagine the danger to unsuspecting practitioners,” he said.

Dr. Ifeanyi tasked the Medical Laboratory Science Council of Nigeria (MLSCN) to urgently step up regulation, ensure reagent validation, and enforce equipment calibration across laboratories nationwide. He also urged faith institutions, civil society, and traditional rulers to intensify public enlightenment on the dangers of marrying two carriers.

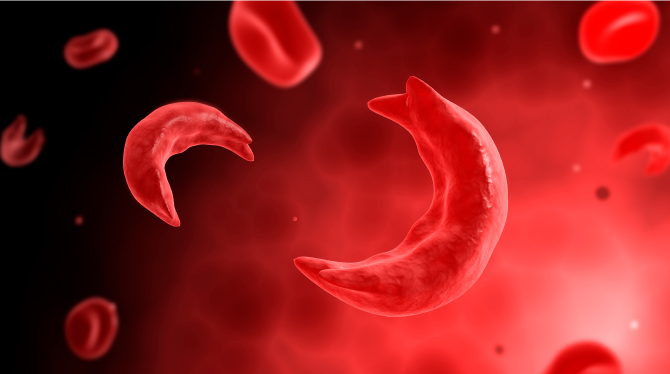

Nigeria bears the world’s heaviest burden of sickle cell, with about 25% of adults carrying the gene and over 150,000 babies born with the condition annually. The disease accounts for nearly 8% of infant deaths in the country.

Despite this, funding for research and local solutions remains minimal. Dr. Ifeanyi stressed that donor agencies supporting malaria and HIV should also invest in sickle cell research, given its endemic nature.

Supporting this call, Prof. Obiageli Nnodu, Special Adviser on Sickle Cell to the Coordinating Minister of Health, cited the 2018 National Demographic Health Survey, which estimated that four million Nigerians live with SCD. Globally, the World Health Organisation (WHO) puts the number at 7.7 million.

“Sickle cell disease is not just a national concern but a global health challenge. We need stronger policy, legislative support, and coordinated NGO advocacy to make real impact,” Prof. Nnodu said.

The Federal Ministry of Health also reaffirmed its commitment to tackling SCD through early diagnosis, awareness campaigns, and improved access to quality care.

“Sickle cell disease is both preventable and manageable with the right policies and clinical interventions. It is not just a health issue—it is a societal challenge that demands collective responsibility,” said the ministry’s spokesperson, Alaba Balogun.