A Reminiscence by Iyorwuese Hagher OON.

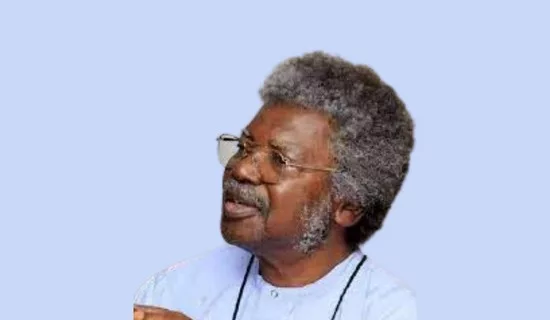

Wanteregh Paul Iyorpuu Unongo, Nigeria’s Stormy Petrel, is no more. For more than sixty years, Unongo dominated the Nigerian political stage. He was a groundbreaking catalyst for social progress, a public intellectual, a revolutionary idealogue, a ferocious fighter for social justice, a cultural icon, a peace-builder, and a perpetual source of political enchantment. Above all, he was the Lion of Tiv and a foremost Nigerian nationalist.

As a young man growing up in Tivland in the Benue Valley, Paul Unongo was nothing special or significant except his good looks. Like other young Tiv children, he was born on fresh green leaves inside his parents’ thatched hut. He suffered deprivation and the horrendous collective despair of Tiv society.

The Tiv lacked everything that made life meaningful. There was no electricity until the 70s; there was a chronic lack of potable water, and there still is. The Tiv were Nigeria’s designated hewers of wood and drawers of water. They sacrificed sweat and much blood-fighting world wars, building the colonial railways across the country and the two major national bridges on the Benue and Niger rivers uniting the country. And they mined the Tin (Kuza) on the Jos Plateau. They died in droves to make the British empire rich.

The colonists appropriated Tiv agriculture and subverted from food production to cash-crop production of export commodities, mainly soybeans and sesame (renamed Benue seed—Benniseed). Tiv farmed and cheaply sold these crops to the British monopolist John Holt, who determined commodity prices. Meanwhile, the colonial government assessed horrendous taxes payable to the colonial government. They labored extensively and got little to nothing for themselves.

Paul Unongo’s academic brilliance saw him through the Nigerian school system. He tasted the feel of fresh, crisp bank notes working in the Barclays Bank and even rose to be a sub-manager. But Unongo had his sights on being much more than a prisoner of bank vaults. He wanted to pursue education to the farthest, and that he did. He came to Canada to study Psychology at the University of Alberta and Edmonton. But he learned much more than mere psychology.

He became radicalized. The Black Civil Rights Movement in the United States profoundly impacted the young Paul Unongo. He enlisted in campus and mainstream Canadian politics that elected Pierre Trudeau, the Canadian Prime Minister, in 1968.

While in Canada, Unongo compared his situation to the appalling conditions of Tiv land, where he came from, and his emerging country, Nigeria, pathetically embroiled in a needlessly shameful civil war. He wanted to return home and make a difference. In his mind, he was both Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Soon enough, opportunity dramatically presented itself.

Biafra was gaining world sympathy from the perception that the Nigerian Civil War was a genocide being waged by Northern Muslims against the Christian Easterners. Unongo’s relative and mentor, the Federal Minister of Transport, Hon. J.S. Tarka, enlisted Unongo’s charisma and loquaciousness alongside Rev. Father Akor in the Nigerian diplomatic response to Biafran propaganda. The duo traveled through Canada and the United States, dispelling the propaganda of Northern Muslims warring with Eastern Christians; they were credible voices. They succeeded in their mission.

Both Paul Unongo and the Rev. Father Akor were Northern Christians. Unongo’s effectiveness as a diplomat endeared him to the Yakubu Gowon administration, and he created yet another opportunity to serve by returning home to start and head the Department of Psychology at the University of Lagos. This became the return, the homecoming, and the rebirth of Paul Unongo to Nigeria’s historical and political significance.

Unongo’s decision to return home to Nigeria and join the politics of agitation did not go well with the Tiv political leadership. Hon. J.S. Tarka was particularly miffed that his hitherto brilliant assistant, Paul Unongo, now back from abroad, had grown wings and had a different vision for Tivland. He had enlisted the new military administration in Jos to erode Tarka’s legitimacy, influence, and grip on Tiv politics.

Unongo’s iconic booklet “Where Do We Go from Here” laid out a coherent manifesto for the nation and Tiv land. He then cheekily announced his arrival on the Nigerian political stage.

“I confess most proudly that I am a Tiv Tribesman but a most dedicated Nigerian nationalist.”

Throughout the sixty years of Unongo’s political reign in Tivland and his activism on the Nigerian political stage, Unongo maintained dual loyalty and allegiance to the country, Nigeria, and his beloved Tiv nation. Paul Unongo’s political mobilization of Tiv cultural dances and performances, finance, the youth, and the elite left little room for Hon. Tarka. Even when J.S. Tarka tried to make a come-back during the Constitutional Conference of 1978, Unongo’s smart moves had Tarka disqualified for not filing taxes on time. Barrister J.T. Vembe, a young lawyer from Mbakor, his immediate constituency, took his place. Unongo led his team of intellectuals to the 1978 Constitutional Conference to craft the 1979 Constitution, while Tarka retreated ruefully into exile to his Home in Highgate, London. He watched the grave of the great Karl Marx from his bedroom window daily. He resolved to return to Nigeria and avenge his humiliation at the merciless hands of his former political mentee, Paul Iyorpuu Unongo.

As the ban on party politics was lifted, Tarka resuscitated his structures of the UMBC and plotted his revenge even as his body was now wracked with cancer. He rallied his traditional base and even recruited young elements from among Unongo’s elite. He formed the National Club that became the NPN, and Paul Unongo likewise formed an alliance with DR. Nnamdi Azikiwe and became Secretary of the Nigerian People’s Party.

Unongo aggressively entered Tiv and Benue politics, carving a vast political niche and creating a mass of passionate followers. He refused to compromise, dialogue, or seek accommodation with the older generation, which equally fawned over their leader, J.S. Tarka, whom the Tiv loved with a blind passion. Unongo referred to Tarka and his political base as “Those Tiv who belonged to that unique group of false apostle politicians of the First Republic.”

The elite versus masses dichotomy was born and has continued to dictate the political pulse of Benue politics. The 1979 elections were the test case of whether Paul Unongo’s NPP would win the election in Benue State or the NPN headed by J.S. Tarka. The NPP lost, and the NPN won with a landslide. But Paul Unongo took advantage of it. He authored the NPN/NPP alliance that ushered in the Second Republic, to the chagrin of J.S. Tarka, who led the NPN to victory. Indeed, but for Shagari’s strong sense of justice and political sagacity, Unongo’s ministerial position would have been a mere pipe dream. Unongo’s adversarial strategy now gave Benue State more than its share of Ministers.

Tiv Land had both Minister of Steel Development in Unongo, while Hon. Isaac Shaahu became Minister of Commerce. Paul Unongo was a profoundly polarizing personality, and the NPP Party never accepted defeat at the polls. Even after the death of J.S. Tarka in 1980, Unongo’s political fortunes dived. Allegations of corruption from irrefutable whistle-blowers confronted him. He resigned from his ministerial post, as J.S. Tarka had done earlier.

Tarka became a Senator, and his son, Simeon Tarka, became a Member of the House of Representatives. He decisively descended on Paul Unongo, whom he described as “Braggadocio.” Throughout the rest of his life, Paul Unongo suffered electoral defeat after defeat. He was hexed and jinxed to run and never win. He serially lost the race to the Governorship of Benue State and the Senate. He lost the nomination for Presidential flag bearer in the SDP under option A4. His candidates also lost to the traditional base of Tarka. Unongo continued to lose until he withdrew from all political contests to be a celebrated elder and statesman. In this new role, Unongo profoundly influenced Nigeria’s Military and Civilian presidents, who found his charisma and intellectual appeal on public policy irresistible.

Paul Unongo’s Legacy to Benue

1. Paul Unongo’s generosity was legendary. He gave scholarships to Tiv youth to study in America and Russia and made critical appointments to Tiv sons like Tachia Jooji and Moses Saror at Ajaokuta Steel Company. Before his Ministerial appointment, Unongo had accumulated a sizeable financial chest, and he built Secondary Schools and a Specialist Hospital in Katsina-Ala, the headquarters of one of the newly created Local Governments.

2. Unongo’s alliance and friendship with the Benue-Plateau Governor, J.D. Gomwalk, split the large Tiv Division into three Local government administrations.

3. Unongo pioneered and cultivated the interest of the Tiv youth in academic careers and pursuits. Unongo claimed, “Concern for Tiv deplorable and unacceptable social condition has forced me to descend from my comfortable ivory tower in Lagos and speak frankly with and to the Tiv people demanding that they face the harsh reality of their miserable backwardness and do something about it.” (Source): “Where Do We Go From Here?”

4. Unongo introduced the Tiv and Benue youth to modernization. He introduced the youth to nightclub life and pop music. Several youths crossed the threshold of morality and became victims of crime and anti-social life. The effect of Unongo on the youth was electrifying and riveting. Although Unongo never drank alcoholic beverages nor smoked, Jos, Gboko, and Makurdi youth danced, drank, and smoked. They also kept late hours at Juladaco nightclubs. They cultivated long hair, wore the peace pendant, and sang the anthem of the Black Power Movement, “Say it loud, I am black and proud.” He spread the music of peace, love, and harmony. Many of my contemporaries abandoned the quest for higher education to follow the cult-like social movement of Paul Unongo.

5. Paul Unongo has significantly impacted Tivland culture. He has changed mores and morals, even dress codes, and awakened interest in Tivland’s traditional religion and rituals. He has imported costly festivals into Tivland and the un-Tiv practice of keeping corpses for a long time without burying them. To cap it all off, Wantaregh Paul Iyorpuu Unongo declared himself the spiritual and political leader of Tivland. These claims have not been contested!

6. Unongo gave his wealth and possessions to the people. No Tiv politician has displayed more incredible generosity than Wantaregh. Apart from scholarships, he gave out loans to farmers without seeking repayment. He made the modern life of education, capital accumulation, and social inclusion appealing. Unongo’s entire existence was a labor of love for the Tiv people and Nigeria. He strove to be a change agent to improve the Tiv people’s deplorable plight and sought social inclusion and justice for all.

Unongo’s Legacy to Nigeria

1. Unongo’s contribution to Nigeria’s civil war effort was genuine and patriotic. He said that he undertook it “on the official behalf of the Federal Military Government. I challenged the wisdom of foreign friends, foreign meddlers, foreign apostles of doom and racial hate, and foreign corrupt organized Churches.”

Unongo’s dual loyalty to the Tiv tribe and Nigeria made many Nigerians proud of their culture, as Unongo was fiercely a Tiv cultural icon. Unongo believed in the power of Nigeria’s diversity and the resolute dignity and rights of the ordinary people who had been robbed of their citizenship by a retrogressive traditional cabal that still treated Nigerian citizens as their conquered subjects despite Nigeria being a republic.

He promoted Tiv republicanism and scoffed at offers to be conferred with a traditional chieftaincy. Brazenly, he gave himself a somewhat whimsical and mystical title, “Wanteregh,” son of the land (Son of man?), which he clung to with magisterial fierceness. He was the iconic Tiv leader and sought to teach Tiv values of integrity, courage, boldness, and justice. Unongo was the bright knight with shiny armor who warred against all injustices. He was a total enigma who took life by its horns, making his rules and creating his political, social, and cultural spaces. He lived and died by his terms.

2. Unongo’s greatest gift to Nigeria was his blunt refusal to cooperate with the enemies of Nigeria who tried to enshrine the Sharia law into the 1979 constitution. Unongo led a team of young intellectuals like Mvendaga Jibo, Solomon Daushep Lar, Abubakar Rimi, Omo Omoruyi, Femi Okunnu, and others determined to have a circular constitution. The supporters of the inclusion of the Sharia law into the Nigerian Constitution made this the most crucial aspect of the Constitution of particular significance. Ultimately, Mr. Unongo’s team prevailed, and the Sharia was left out of the 1999 Constitution. Unongo had won his first major political battle, determined to have a secular nation where religion is private and the Constitution is secular.

3. Unongo was Chair of State Creation at the Constitutional Conference in 1994-95. I was an elected member, and he was a government nominee. I nominated him as Chairman, and we worked hard to create the Apah and Katsina-ala States. But we failed even as Unongo, like Odili, was removed from the all-powerful Chairmanship position that created new states. We successfully recommended the creation of six zones for the country and the establishment of the Federal Character Commission.

Unongo as my Leader

I was in my final year of secondary school in 1968 when Unongo colonized Gboko town. He drove into Gboko with a long convoy of costly cars. He had a security outfit of hundreds of veterans. These security men mounted a guard of honor for Unongo every morning and marched through the town. Unongo’s veteran guards were rumored to have firearms. Unongo was handsome, articulate, elegant, and debonair. He was rarely seen, yet he had a ubiquitous presence, and many youths deserted dormitories to hang around and glimpse the legend. I adored him. I coveted such opulence and his clever ways and overflowing intelligence and confidence.

But I equally feared and hated his moral ecology of excessive permissiveness in breaking barriers and taboos. I was too timid to try these. I also resented him because J.S. Tarka was my first idol. I was born into the Tiv resistance movement against the NPC and its doctrines. To my youthful sensibilities, Unongo stood for all that was despicable, evil, and reprehensible.

My father, a school headmaster and UMBC activist, a Tarka fanatic, laughed at Unongo’s antics. He believed Unongo’s source of wealth was purely satanic. Tarka had nicknamed Unongo “Braggadocio,” and his followers laughed at Unongo’s antics as merely comical. The Tiv had never seen such concentration of wealth, education, and good looks. I was a young pioneer- (Yan Panya) of the UMBC. My best friends, Peter Dzoho, Yima Sen, and Mfa Ikpa, left their jobs, and Peter abandoned the University to work for the Unongo organization. I held back with great restraint.

Later in life, I drew nearer to Wantaregh, or more correctly, we drew nearer to ourselves. We were in the same Senatorial zone, and when I ran for Senate in 1983, Unongo’s NPP candidate, Chief Atongo, stood down and supported me in the NPN to victory. Despite this, we drew nearer, and his wife, the ever-adoring Vickie Avarave Unongo, my maternal Aunt, made being friends with Unongo so much easier.

When I was nominated Minister in 1995, my leader, Unongo, summoned me to his house in Jos. He convinced his core supporters of why he withdrew his interest in the ministerial position and demanded that they cooperate with me. In 2001, when the Tiv race was on fire, and Tiv people were being killed in neighboring states, Unongo, alongside me, Iyorchia Ayu, Joseph Waku, and General Atom Kpera, worked for peace under the umbrella of the Mzough U Tiv.

Unongo assiduously worked for Northern Unity in his senior age and tried to bring peace to the North. We were both members of the Northern Elders Forum (NEF). When, during the Buhari administration, the herders and bandits started assaults and killing of Tiv in Benue State, we continued to dialogue with other Northern leaders. Unongo used his position as the acting Convener of the Northern Elders Forum to condemn wanton ethnic racism, banditry, and genocide against the Tiv.

Unongo’s Last Public Outing

A week before his final hospitalization and death, Unongo attended a meeting of the Northern Elders in Minna with IBB and in Abuja. On Tuesday, 20 April 2022, Unongo made his last public outing. He asked me to meet him at the Peniel Apartment and escort him to meet the Governor of Benue State, Dr. Samuel Ortom, his political protégé.

When we arrived at Ortom’s home at Games Village at 11:am, I held his left arm, and his beloved son Tyolumun Unongo held him on the right side. Slowly and gingerly, we climbed to the top steps and were ushered into Governor Ortom’s living room. The Governor joined us quickly when he was informed. In total embarrassment, Ortom tried to blame me for troubling his leader, Unongo, from coming when he was the one who traditionally went to visit. But Paul Unongo absorbed the blame and most tearfully recounted how, in the past, Wantaregh had invested heavily in his goodwill to allow the young Ortom to enter politics as Chairman of Guma Local government. He begged Ortom to “bury” him by giving Tyolulum Unongo the ticket to contest the election for the House of Representatives. There was no way the Governor could refuse this request. He accepted all of Unongo’s appeals for his son. Tears flowed down my cheeks as I witnessed this ordeal. It was a political deja vu moment. History was repeating itself.

I remembered how 1979 Hon. J.S. Tarka had similarly requested that we, the NPN Caucus in Benue State, give his son, Simeon Tarka, nomination to the House of Representatives. Simon Shango, a motley band of young party men, and I vehemently opposed this as undemocratic and demagogic. We were foolish and shallow. Tarka sniffled, and tears rolled down his face. With Tarka crying, the meeting had to end abruptly. The following day, the party elders approved Tarka’s request when Tarka confided in his health situation that the doctors had given him only a few more months to live. Hon. Simeon Tarka was elected to the House of Representatives the day his father was elected Senator. Tarka returned to the hospital in London soon after he won the 1979 elections, and a few months later, he died a happy man.

The meeting between Ortom and Unongo, both of the Ichongo lineage, and me, from the Ipusu lineage, was chilling and ominous. That same day, 20 April 2022, Unongo left for Jos and was hospitalized. It was his last public outing.

Tyolumun Unongo was not nominated on 5 June 2022 as agreed. Political difficulties and overwhelming forces tied His Excellency Governor Ortom’s hands. If Unongo had succeeded in his appeal to elect Tyolumun, he would have finally earned a political victory. After a series of political setbacks, Unongo had an uncanny belief that his name, Iyorpuu, was a bad omen. Since Tiv’s names were prophetic, Iyorpuu means people disapprove, but Tyolumun means the people approve. Tyolumun was not meant to lose an election. Wantaregh Paul Iyorpuu Unongo never left his hospital bed till he gave up his ghost five months later.

Wantaregh has left us when there is still so much to be done. Our country, Nigeria, still oozes from the social tumor of virulent poverty and deprivation. The Nigerian political class still generates economic spoils for itself by manipulating ethnic cleavages. Nigeria is still the World’s third-largest Christian and fourth-largest Muslim country. Now that Wantaregh is no longer there, who will have the fearless grace to tell Nigerians to show the World the power of tolerance and love?

Who, like Unongo, will stand with the oppressed whose lives are perilously fragile and raise a voice for their defense?

END OF AN ERA

With the passing of Wantaregh, all of us who have inherited the Leadership Mantle of Tarka or that of Wantaregh are now political orphans. It is time to declare the end of an era. It is time to break down the walls that have held us prisoners and prevented us from creating history together. It is time to hold hands and remember our common political ancestry. It is time to say no to guile, greed, and disrespect.

May the soul of our hero, our leader of all seasons, Wantaregh Paul Iyorpuu Unongo, rest in peace!