Education, whichever way defined, is the major factor in human progress, throughout human history. Human development, which is the modern synonym for human progress, is entirely contingent on education. The relationship between education and development is so inextricable that you cannot have the latter without the former. And because human development is critical to human life, education, without which there cannot be development, is critical to human society. The nexus between education and development is therefore just as critical. So, in proposing to speak about education and development, we are seeking to address a fundamental pillar on which rests human civilization. In doing this we may have to go back to the first principles to examine the fundamental concepts of education and interrogate contemporary assumptions. I am quite aware that some may find this boring for a start, or even dismiss it as hair-splitting academic contentions, but this is no reason to lower the quality of our discourse.

My intransigence should not be too difficult to understand, for we have already lowered the quality of our political leadership and see the sufferings we are going through. If we should lower the quality of our intellectual discourse then what hope can be there for recovery?

Education must necessarily lead to human progress if it is to serve its intrinsic purpose. Humans have been crafted and wired to think and function rationally. The measure of their rationality and functionality is a measure of their understanding. Since the beginning of human consciousness, philosophers and mystics have been concerned with human understanding. One of the earliest debates around human understanding is Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics. David Bronstien’s book, Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning: The Posterior Analytics, is thought to be the best illumination of the reconstruction of Aristotle’s account of learning. This Posterior Analytics sparked debates that contributed to the emergence of a branch of philosophy known as epistemology or theory of knowledge, which concerns itself with how we know what we know; how we distinguish knowledge from opinion and how to separate truth from conjecture. Without this meticulousness we are bound to grope and fumble in the confusion we find ourselves today, which is why in the last 25 years of democracy we have NOT been able to develop, if anything, we have only doubled our poverty, escalated our insecurity, destroyed our institutions and dashed the hopes of an increasing number of young people who can see no future in the ever-decomposing society they find themselves trapped into.

For the records, Africa was actually educated before Europe. The first university in the world is the University of Qarawiyyin, founded in 859 AD located in Fez, Morocco. The second university in the world is the al-Azhar University founded 970 AD located in Cairo, Egypt, the third university in the world is the University of Sankore, founded in 989AD, located in Timbuktu, Mali. The first university in Europe, on the other hand was the University of Bologna, founded in 1088 AD in Bologna, Italy. It should be interesting to note further that the University of Qarawiyyin was built by a woman called Fatima al-Fihri, when she died her sister completed the building. The university of Al-Azhar was built in honor of a great woman, Sayyida Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad. The Sankore University was built by another woman, a Bambara business woman. Europe was actually woken up from its slumber by the flourishing Muslim Polity established by the Al-Moravids Movement in the 11th century. The Al-Moravids, better still, al-Murabits, is an African movement that took over Spain and turned it into an intellectual hub that stimulated medieval Europe and sparked the renaissance of the 15th and 16th century. The details of this are contained in the seminal work of Professor George Makdisi, titled, ‘The Rise of Colleges: Institutions of learning in Islam and the West.’ It suffices to quote a towering Western orientalist, Montgomery Watt, where he said,

“Not only did Islam share with Western Europe many material products and technological discoveries; not only did it stimulate Europe intellectually in the fields of science and philosophy; but it provoked Europe into forming a new image of itself. Because Europe was reacting against Islam, it belittled the influence of the Saracens and exaggerated its dependence on its Greek and Roman Heritage. So today an important task for our Western Europeans, as we move to the era of the one world, is to correct this false emphasis and to acknowledge fully our debt to the Arab and Islamic world.” [a lot of what Europe calls Arabs are actually Africans and Persians] Prof George Makdisi, himself added that, “On the other hand, it is common Knowledge that the West was not oblivious of the higher civilization of Islam: it learnt its language and translated its works in order to bring itself up to the level of the higher culture, the better to defend itself against it.”

Before diving into the core of our topic, perhaps we should tarry a little to clarify what exactly is a university? Here I find the experience of Professor Simon Leys very cogent. Leys was a sinologist who spent his life in the university system and left it just when it stopped being one, as summarized in his succinct article. He titled his article ‘An Idea of the University’, as a homage to Cardinal Newman’s ‘The Idea of a University”, which has remained a classic work on university education seeking to broaden and deepen knowledge in the face of secular constraints. Leys was addressing two important aspects of the university, the ivory tower, a place of intellectual excellence and the tide of shit hitting its wall trying to undermine it. In other words, a struggle between knowledge and ignorance. In addressing the ivory tower he took what he considered to be a generally accepted definition of a university. He said, “a university is a place where scholars seek truth, pursue and transmit knowledge for knowledge’s sake – irrespective of the consequences, implications and utility of the endeavor.”

He proceeded to explain that a university needs four things to function, two of these essential and the other two nonessential. The two essential requirements are scholars and a good library, the non-essentials are students and funding. The scholars are most important of all for they are the university. The administrative staff, including the vice chancellor are only there to facilitate learning, i.e., the pursuit of knowledge.

“The demand for equality is noble and must be fully supported, but only within its own sphere, which is that of social justice. It has no place anywhere else. Democracy is the only acceptable political system; yet it pertains to politics exclusively and has no application in any other domain. When it is applied elsewhere, it is death – for truth is not democratic, intelligence and talent are not democratic, nor is beauty, nor love – nor God’s grace. A truly democratic education is an education that equips people intellectually to defend and promote democracy within the political world; but in its own world, education must be ruthlessly aristocratic and highbrow, shamelessly geared towards excellence.”

But perhaps we should add a clarification here regarding the constant complain of universities main vocation, search for knowledge. In our days and age too often we hear complaints that this is ‘academic’, a euphemism for utopia and lack of practicality. One can dismiss this as sheer dumbness, but it may help to explain. The vehicles we use for our logistics, the plain we fly to places, including places of worship like Makkaor Jerusalem, the phone we are holding … are all pieces of technology with precision engineering, that are there precisely because of the academic research and standards.

Without academics a lot of these practical gadgets would not be there for us to use. This human folly goes back to the times of the Greeks when Socrates, who was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens, was once asked, ‘Of what use are philosophers?’ He immediately replied that philosophers are of no use. The man was visibly happy and was leaving when Socrates told him but you did not ask why they are of no use? He then asked why are they of no use? Socrates replied him: ‘because people don’t know how to make use of them’.

It is well over fifty years since this famous speech, yet not much has changed. For what I know, today the values in the campuses contrasts diametrically with the values of the wider society in which these universities are located. The campus communities often look down with contempt at the wider society, while the wider society looks at the university communities with suspicion, they see them as some weird strangers symbolizing values of some foreign cultures. How then can the content of these institutions relate to or even make sense to the wider society? This is why it is still pertinent to place the issue on the table and project it on the radar so that we can address the issue. I recall how in 1995 I was invited by the Usman Dan Fodio University to speak to some medical students on medicine. I chose to speak about the contribution of the Sokoto Caliphal scholars to the study of medicine. You need to see the shock on the face of many in the audience when I referred to about one dozen different works of the scholars on different aspect of medicine.

That medical students in a university in Sokoto will go through a complete course of medicine without any idea of the contribution of scholars revered by the wider society in their chosen field of study, speaks to the incongruity and even insolence of the content of our education.

Yet another dimension of the challenge of content is in the field of skills. Today the world has changed. What the world needs is skills more than degrees. See the rise of China and the developments in India.

Today the global economy is being driven by skills and nations are struggling to up-skill and reskill their workforce with the changing landscape of technology. Nigeria largely imports skilled labor to deliver major projects such as Refineries, Urea plants, Natural Gas Pipelines, Railway expansion, and if care is not taken the upcoming Mambila Power Project requiring about 50,000 skilled labor at its different stages. Our universities and polytechnics are only producing academically trained products with little hands-on skills qualifications. This narrative must change if Nigeria is to move forward. In 2014, China converted many universities (600) to skills Institutes to remain on top of the curve in the production of skilled manpower globally. With the spread of digitization and automation and the flourishing of artificial intelligence, the work environment is also changing and our educational system must accordingly take a cue from these changes.

The challenge of competence is the concern for standards. The concern about the quality of the products we produce from Nigerian universities. The concern about our competitiveness in the global economy where knowledge is the greatest capital. Our standards have clearly been falling. We may argue about the metrics, but those employers of labor, both at home and abroad, have been reporting very disturbing experiences. I am not sure of how much empirical study has been done to establish these or even the national metrics to evaluate. But the experiences on the ground for those who employ NYSC labor has been appalling. Graduates of old were thoroughly trained and could compare with their counterparts in Europe. Not today. All these have implications for our future as a nation which can only survive and thrive if it is able to compete in the highly competitive environment of the 21st century. Today our competence is our greatest asset for it is the best capital that we can leverage to remain in business.

Maybe a few comparisons may help drive the point home. Let us use the more familiar ones. Malaysia picked the palm oil seedlings in the Sixties from Nigeria, today they are the leading world producers of palm oil and they have developed out of it about 360 different products. India has become a world class IT hub it has produced competent IT experts that many of them are heading the IT corporate world. Many of the CEOs of global IT companies are almost all of Indian in origin. About a decade ago India made more revenue out of IT then we made out of oil, even as oil was then selling about 100 USD per barrel. The case of Brazil is even more dramatic. Brazil is leading in agricultural production and processing. It is supplying the Arab world with their beef needs and supplying Nigeria with poultry and grains. In the Seventies Nigeria and Brazil built similar defense industries, since the 80’s Brazil has been producing F5 fighter jets while ours, until 1999, was only producing furniture. By 2015 Brazil was planning to invest $120bn in its export-oriented military industrial complex. It is jointly, along with Argentina, Chile and Columbia, producing KC390 Military transport plane and by 2016 first nuclear powered fast attack submarine. All these speak to as much about the quality, or lack of it as it were, of our leadership as the quality, or lack of it, of our manpower.

Today, we are much way behind our peers. Some of the young people I am mentoring, who are doing their post graduate studies in the universities are reporting to us the flourishing of an industry that writes theses and dissertations for students for a fee. So, we graduate students who cannot even defend what they are supposed to have written. Some of our children in our universities used to report to us about lecturers selling hand-outs that are copied from books and if you don’t buy, you can’t pass the course they teach. There are a lot more on this than time can allow us to reel out. But I must add that a few years back I made an attempt to return to the classroom after my sojourn in politics. A close friend and a professor of history, who spent a good time teaching abroad, warned me that I cannot, because the universities were no longer what they used to be. I ignored him and went ahead only to discover that he was right; students were no longer ready to learn, everybody was just looking for a certificate, the teachers themselves were busy copying and pasting just to become professors, it appears like no one was interested in competence. The universities were beginning to look like some academic fraud with professors leading a cartel out to destroy the sanctity of learning, even if inadvertently. What a tragedy for the nation that the whole continent of Africa is looking up to for direction!

The challenge of character in our universities is perhaps the most serious of all the challenges. Character has always been an integral part of education. Our convocation protocols continue to repeat the mantra that graduates are being conferred with degrees ‘in character and in learning’. Putting character even before learning is to stress the prioritization of character over learning. Yet what we hear and see in the universities today continue to breach these protocols and empty its meaning and significance. The media is replete with stories of plagiarism, examination malpractices, cultism, abuse of psychotropic drugs, sexual harassments and a host of other character deficits from our universities. Yes, the wider society itself is immersed in these evils and it is just as worrying. But when the breeding ground of the future becomes so infested it means the hope for change is dim and we may need to brace up for the worst.

That today we have the wider society immersed in these evils could also be because the wider society is run by graduates of our universities, who are the elite occupying and leading the public institutions and the private enterprises and who are destroying these institutions, stealing us blind, frustrating development and creating the chaos we call Nigeria, where nothing works. One could go further to add that what the terrorists and the bandits who, have not gone to the universities, are doing is what the elite, graduates of our universities appear to be doing in a more sinister, more sophisticated and more devastating fashion. The political class in particular, many of whom have degrees or diplomas from our universities are at the center of the social, economic and political crisis that has stunted our growth as a nation and brought us to the precipice. How much of all these burdens can be placed at the door steps of our universities may be a matter of debate.

These questions might look strange today or even unfair to university administrators, after all they operate in a secular atmosphere where they are restricted from interfering with the morals of people. I hope we can all see the dilemma in which we have found ourselves. If we trace our steps back some two to three hundred years ago, we shall see that the universities of Oxford and Cambridge that we sought to copy were Christian religious seminaries that focused on as much in science and technology as they did in character and decency. The erosion of this component of education came with the so-called period of Enlightenment which banished God from the equation and substituted Him with man with all his whims and caprices. And we can see where these have taken the West: now we don’t who is a man and who is a woman, or who is he and who is she, or who are they and who are we, and the confusion rages on. Is this where we want be?

In reviewing the literature on this subject, I found a number of academic and non-academic articles on the subject, some of which have documented specific cases on the subject, even as they admit that most cases of character breaches go unreported. Most of this literature lament the problems and keep tip-toeing around the issues. Their recommendations appear only to beg the question or reporting the hyena to the dog which can at best only bark. I could not find any solutions in the literature that are bold and game changing. Considering the fact that we are today led politically by people with character deficits, whose leadership has thrown our country into the abyss, where the poor is just trying to breath and when other nations, far less endowed, are rising and pushing us down the ladder, when are finding ourselves on a trajectory of extinction, then the issue of character has become existential. If we can’t fix it, I really cannot see how we can survive the next decade of the 21st century.

In this piece, I have attempted to raise the issues around the challenge of content, competence and character in the Nigerian universities. The challenge of character is the most critical of all, for without addressing it and fixing it, it is inconceivable if anything can change. These issues are inextricably linked to our development as a nation. In the highly competitive environment of the 21st century, we can only survive and thrive if we are able to address and resolve these issues in good time. The world is not going to wait for us. Our tragedy is that our political leadership is in a different world of frivolities and rackets. I am not even sure if they can understand these issues much less engage with them. The choice is ours, either to play safe and keep quiet while our country goes down the drain and live a life that is short and brutish or live up to our education by summoning the courage to stand up to these assaults on our persons, our dignity and our future.

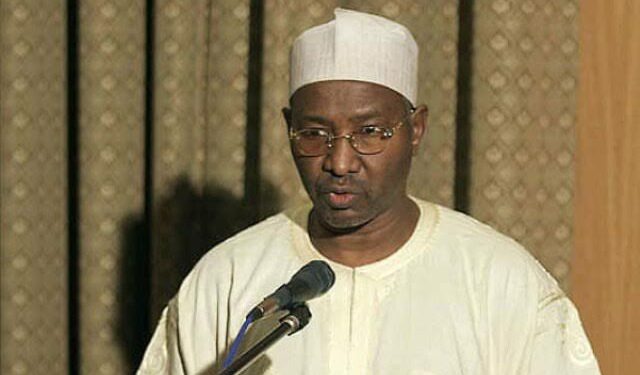

* Being a paper presented by Bugaje, PhD, during the recent convocation of the Gombe State University.