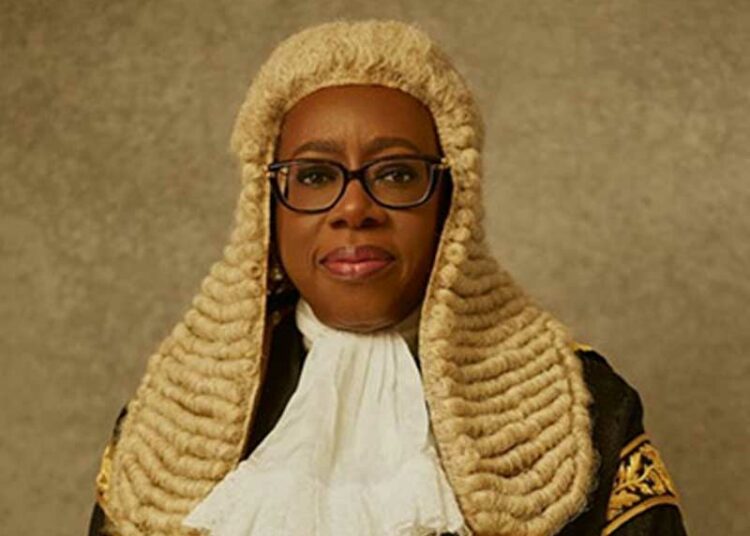

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has just sworn in Justice Kudirat Kekere-Ekun as the 23rd Chief Justice of Nigeria and the new head of the Nigerian judiciary. The 66-year-old jurist is the second female justice to hold the office after Justice Aloma Mariam Mukhtar.

At the swearing-in ceremony, President Tinubu charged her to immediately embark on reforms that will uphold the judiciary’s independence, strengthen all mechanisms for integrity, discipline, and transparency in the judicial sector, and pursue other initiatives to sustain and rebuild public confidence in the third arm of government.

In her response, Justice Kekere-Ekun pledged to restore confidence in the judiciary, indicating that she knew that that arm of government had developed an image problem. She admitted that the controversial appointment process in that arm of government needed to be addressed. This was just as she pledged to tackle all issues relating to her office and job description comprehensively. Also, she promised to leave behind a judiciary that the country will be proud of, one in which operational efficacy and public trust are present.

However, much as we are inclined to give her the benefit of the doubt, reversing the existing negative public perception of the judicial arm of government is a tall order, to say the least.

In 2023, a survey by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes and the National Bureau of Statistics, “Corruption in Nigeria: Patterns and Trends,” claimed that judges topped the list of bribe-takers in the country, followed by officials of Customs and Immigration, the armed forces, land registry, and police in that order.

Earlier, a December 2020 report of a survey conducted by the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) found that lawyers paid to judges N9.4 billion in bribes between 2018 and 2020. The report claimed that corruption in the justice sector was heightened by the “stupendously high amounts of money offered as bribes to judges by lawyers handling high electoral and political cases.”

The issue of pervasive corruption in the judiciary is not new. Decades ago, eminent jurists like Justice Kayode Esho spoke about billionaire judges, while Justice Sylvester Chukwudifu Akunne Oputa and a few others raised concerns about corruption in the Nigerian judiciary. However, it perceived to have taken a dangerous dimension in which individuals brazenly flout the laws and tell their victims to go to court. There are so many high-profile cases, including publicly captured offences and confessions of law-breaking, in which the judiciary has returned verdicts that have frustrated Nigerians.

Justice Kekere-Ekun has her work cut out for her in stemming this cankerworm of corruption in the institution. As a newspaper, we hold that in a nation where the executive and legislature seem out of tune with reality in the country, the people look up to the judiciary to maintain order through the instrumentality of the law. Unfortunately, in our view, the judiciary has unwittingly become a willing tool in the political class’s exploitation of the masses. As a result, the judiciary is no longer seen as the last hope of the common man.

Nigerians expect Justice Kekere-Ekun to address the concerns of fellow Supreme Court justices Dattijo Muhammad and her predecessor, Justice Ariwoola, in their valedictory speeches.

Muhammad had expressed misgivings about the lack of transparency and accountability in the funds allocated to the judiciary and the over-concentration of power in the hands of the Nigerian chief justice, who is chairman of the National Judicial Council (NJC), which oversees both the appointment and discipline of judges, chairman of the Federal Judicial Service Commission (FJSC), chairman of the National Judicial Institute (NJI), and chairman of the Legal Practitioners Privileges Committee (LPPC) that appoints Senior Advocates of Nigeria. The concern is that in performing these tasks, past CJNs neither conferred with fellow justices nor sought their counsel and input on any matter related to these bodies. He suggested that this needs to change as it lends itself to possible abuse of power.

For his part, Justice Ariwoola decried delays in accessing justice and pointed out that the Supreme Court is a policy court and should not be burdened with all manner of cases. To this extent, therefore, the new CJN should find a way to unclutter the justice administration system, where cases linger in the courts decades after the litigants are dead and where about two-thirds of those languishing for years in jails have not even been convicted.

We are not asking the new CJN to reinvent the wheel. There are already enough recommendations from judicial reform efforts, including the Justice Sector Reform Summit held in April this year, a collaborative effort of the Ministry of Justice, the National Judicial Institute and the Nigerian Bar Association to rely on.

As a newspaper, we agree with Kekere-Ekun’s predecessor, Ariwoola, and other patriotic Nigerians that the far-reaching decisions made at the summit will significantly assist the justice sector. While we congratulate the new CJN on her elevation to the head of the third arm of government, we urge her to make her four years on the saddle count remarkably.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel