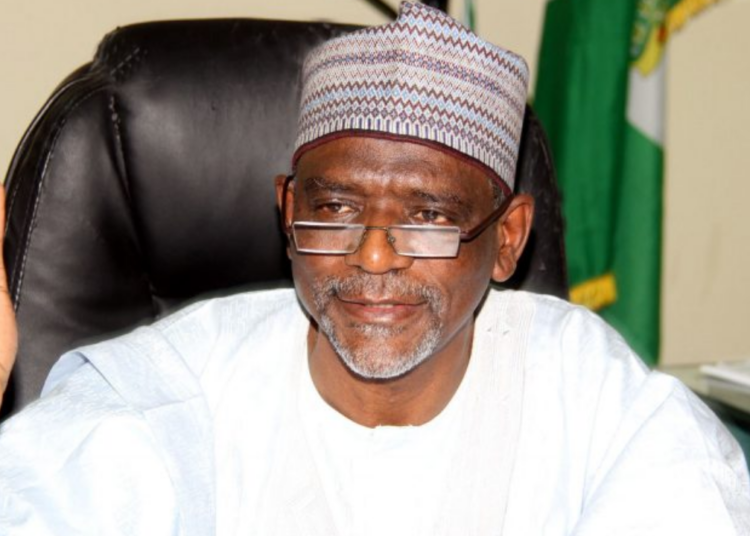

The Federal Executive Council (FEC), early this week, approved the establishment of 36 new private universities. This brings the total number of universities licensed by the Muhammadu Buhari administration since 2015 to 72. The Minister of Education, Mallam Adamu Adamu, justifying this said it was part of the government’s policy directed towards meeting the desire of young Nigerians to access education at the tertiary level.

In the opinion of the minister, “We need more universities. The existence of many universities should not deter the creation of new ones. Besides, these are private universities.”

With these additional ones, Nigeria now has about 222 universities, according to the National Universities Commission (NUC), the agency that regulates and supervises the nation’s university system. These are made up of 50 federal universities, 61 state and 111 privately-owned universities.

It is instructive to note that despite the existence of this high number of universities in the country, the demand for university education still far outstrip the available spaces as more Nigerian youths desperately seek admission into tertiary institutions.

Of the 1,761,338 candidates who registered for the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (UTME) through the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) last year, 2022, only 500,000 got placement in the universities.

For this year, 2023, the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board (JAMB) disclosed that the Board registered a total of 1,595,779 candidates for the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (UTME), which it said, fell short of the projected 1.6 million for the entire exercise.

However, this number does not include the Direct Entry component of the exercise, which commenced in February, 2023 before it was later put on hold the same month. Suffice it to say that in spite of the high number of universities, there still exists a huge gap of unmet need for those desirous of gaining admission into tertiary institutions.

Regardless, experts in the education sector are concerned that the large number of tertiary institutions has not in any way translated to quality of content or even infrastructure expected of a university. They aver that the nation’s citadels of higher learning have been embroiled in one controversy or the other bordering on allegations of cultism, sex for marks, exploitations among others just as the system has become impoverished by the mass production of graduates that cannot defend effectively the certificate they possess.

They also claim that part of the problem is the incessant industrial actions by lecturers which invariably keep the doors of the mostly government – owned schools shut for longer period of time. The showdown with government is, usually, over wages and entitlements.

It is on record that between 1999 and 2022, lecturers at Nigeria’s public universities were on strike 17 times for what they described as underfunding of the system and the failure of the government to implement agreements reached with them as well as inadequacy of Infrastructural, teaching, learning and research facilities.

The impact of these strikes has been quite consequential on the students who bore the brunt of these lecturers’ absence in classrooms with poor outcomes when they graduate. The high rate of unemployment in the country, no doubt, is as a result of this development as most of the students are assumed to unemployable.

The World Bank and the Industrial Training Fund (ITF) have at various times and fora called for the review of the university curricular, as they posited that the quality of Nigerian graduates is not up the required standard.

In terms of global ranking, Nigerian universities are worse off as no Nigerian university ranks among the first 20 or even 30 in some of the indices; a marked deviation from the past where the premier universities like the University of Ibadan (UI), University of Nigeria (UNN), University of Lagos (UNILAG) and Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU, used to be university education destination of choice for foreign students and lecturers who want to join the faculty or on sabbatical.

Another argument against the proliferation of tertiary institutions is that the manpower needed to operate them are not expanding at the same rate in quality and number. In our considered opinion, it is not enough to provide licenses to every applicant as some of them are politically and economically motivated with no desire to make available the facilities required to make them universities.

It is pertinent, in our view, that deliberate steps are taken to ensure that the ones in operation attain global standard and competitiveness. To achieve this, we urge the agency that regulates and supervises the nation’s university system, the National Universities Commission (NUC), to wake up to its responsibilities.

Without doubt, there is an urgent need to review and come up with curricular that are in sync with the 21st century standards so as to be able to equip and inculcate in the young minds, innovative and educational skills that can bring them at par with the rest of the world. The emphasis, in our view, ought to be on an enhanced standard which mushrooming of institutions will not guarantee.

We’ve got the edge. Get real-time reports, breaking scoops, and exclusive angles delivered straight to your phone. Don’t settle for stale news. Join LEADERSHIP NEWS on WhatsApp for 24/7 updates →

Join Our WhatsApp Channel