To what extent does the last presidential election in Kenya foreshadow what is likely to happen in Nigeria in 2023?

I am not one to draw undue parallels, knowing as I do that there are different intervening variables and sub-texts which may render a blanket generalisation sterile. However, there are many similarities that signpost the possibility of hidden meanings for the perspicacious Nigerian observer. In the tempestuous politics of Kenya, water did run uphill. Can it happen in Nigeria? Is the Kenyan Oracle foretelling something for Big Brother Nigeria?

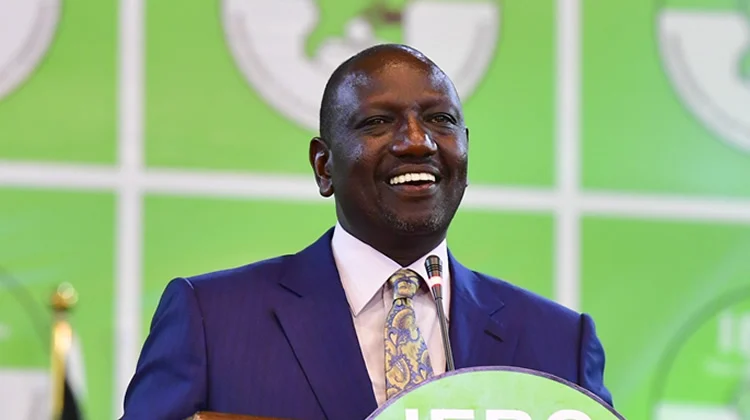

The messaging of the President-elect, William Ruto, at the onset of campaigns reminded one of our own Goodluck Jonathan. He told the rags-to-riches story of how he sold live chickens and groundnuts on the highway as a young boy in order to make ends meet. He walked barefoot until age 15 when he acquired his first pair of shoes. He has since made good for himself with a solid educational background up to doctorate level and a sprawling business, including a 2,500-acre ranch, investments in the hospitality industry, an insurance firm and a gigantic poultry farm.

By all traditional calculations, Ruto was an outsider. He was a nobody. Indeed, he once joked that the even-handedness of democracy made it possible for him, the son of a nobody to enter political contestation with the children of somebodies — referring to the duo of President Uhuru Kenyatta and Hon. Raila Odinga, both of whose fathers were the founding president and vice-president of the country respectively.

His message resonated with the vast majority of the people, particularly rural folk and the youths who, indeed, were desperate for a political champion they could relate with. His electoral pitch to what he characterised as the “hustler nation” was anchored on getting a better deal for ambitious and hard working young people who are frustrated by the current system. He pledged to harness their talents, energies and ideas so that they could play a major role in the making of a new Kenya.

If you consider the fact that the demographics of Ruto’s hustler nation, — those at the bottom of the pyramid to whom he has pledged to bring durable growth — resembles that of Nigeria’s millennials who midwifed and prosecuted the EndSARS protest in 2020, you can begin to understand why nobody can rule out an electoral revolution championed by Nigerian youths in 2023.

Ruto is a millionaire who has managed to detach himself from the elite class. In his “We”versus “Them” rhetoric, you would think he was scrounging for the next meal like the rest of his youthful followers. You could say he orally committed class suicide so as to level up with his lowly constituency. Public relations scholars must be fascinated by how one rich man can be seen to be a fellow poor man by the majority poor just because he comes down to their level and speaks the language of the streets.

Who among the presidential candidates roughly approximates Ruto within the Nigerian political space? If Kenya is any indication, the ‘usual suspects’ may not make the cut in 2023.

Like in Nigeria, there was a generational undertone in several aspects of the campaign. The younger generation wanted someone more attuned to their digital ways. The old guard, represented by the venerable 77-year-old Hon. Raila Odinga, made its calculations based on tribal loyalties and elite consensus. President Kenyatta endorsed his old foe, Odinga, with the hope that the dynastic rumble of ‘Turn-By-Turn Kenya Ltd’ would once again prevail. In terms of the established wisdom of traditional politics, victory was a foregone conclusion.

But, against the law of gravity, in the 2022 elections, water ran uphill!

The famous heirs to the Kenyatta and Odinga political dynasties, Uhuru and Raila, are the greatest losers. Kenyatta has come to the end of his decade at the helm. Had Odinga won, Kenyatta could at least expect to be relevant in the scheme of things, knowing that he helped install his successor. But Fate had something different in store.

Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party was routed in Mt Kenya which was expected to be one of his strongholds. Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) won most of the parliamentary seats. Kenyatta is the patron of the Azimio Council, comprising his Jubilee, Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) and 21 other smaller entities. Azimio la Umoja (Swahili: “Resolution for Unity”) had Raila Odinga as presidential candidate and Martha Karua as deputy presidential candidate. The fact that the power of incumbency didn’t count for much in deciding who won, is instructive.

On that account, can one nurse a fleeting flashback to the last governorship polls in Nigeria’s Osun State where incumbency counted for nothing?

Peter Kagwanja, a columnist with the Kenyan Nation newspaper traced the current state of affairs to the fact that Kenya has had a history of many coalitions by rival political parties aimed at wresting power from the ruling party. Oftentimes, once the aim of attaining power is achieved, the constituent parts of the coalition go back to the trenches causing unnecessary distraction for the government.

The Kenya African National Union (KANU) ruled the country for 40 years before its decline. President Mwai Kibaki flew the flag of the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) for his first term, however he opted for a newly cobbled party, the Party of National Unity as the political vehicle for his second term in 2007. In 2013, Kenyatta’s The National Alliance (TNA) went into coalition with Ruto’s United Republican Party to form the Jubilee Party with a coterie of smaller parties in tow.

“The lesson from the Kibaki era” argues Kagwanja, “was that special-purpose vehicles cobbled together just for winning elections were unstable by their very nature, and when they won power, contributed to a government hampered by internal feuds and power struggles, and consequently to national instability.”

That observation is certainly true of Nigeria where alliances and mergers are orchestrated to capture power after which political jujitsu becomes the raison d’être of all engagements and calculations while governance takes a back seat. It happened with the NPN/NPP accord in Nigeria’s Second Republic. It is happening with the APC currently in control of the reins of power at the federal level. These contraptions are designed to create a distance between the falcon and the falconer, causing things to fall apart.

Talking of similarities between happenings in Kenya and Nigeria, Dr Ruto decamped from the Jubilee Party to the United Democratic Alliance when it became clear to him that his boss, President Kenyatta wanted Odinga to succeed him.

In Nigeria, Peter Obi left the PDP for the Labour Party when it became clear to him that the process for the presidential primaries had become dollarised. In the same vein, Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso left the PDP for the NNP to fashion out a possible way to power through that brand new vehicle.

The defection bug which infests relevance-seeking politicians in Nigeria is also active in Kenya. Already, the outgoing Governor of Mandera County, Ali Roba, has abandoned Raila Odinga’s Azimio movement to join President-elect William Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza coalition.

Sounds familiar? In Nigeria, haven’t we seen state assembly legislators defect to the opposition party as soon as a court verdict or some other process overturns a governorship election in favour of the opposition? Politicians, be they Kenyan or Nigerian or American, don’t like the wind of political winter.

Meanwhile, Odinga’s Azimio Party with 159 legislators and Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza with 161 seats are battling for control of Parliament. Ten out of the 12 independent MPs in Parliament have indicated their intention to join Dr Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza. Azimio has 21 elected county governors while Kenya Kwanza has 22. Neck and neck, no doubt, but Ruto and his Kwanza coalition have just that slight edge that makes for victory.

The Azimio Party is heading for the courts to reverse the declaration of Ruto as winner of the presidential election. Ruto on his part is already rallying the troops. “There is no looking back now, we are looking to the future. We need all hands on the deck to move forward,” he said.

Perhaps if Nigerians were to choose between the presidential candidates in Kenya, they would still have voted for Ruto. Reason: his firstborn daughter, June, is married to a Nigerian, Dr Alexander Ezenagu, an Assistant Law professor at a university in Qatar.

And if Nigerian youths, like their Kenyan counterparts, decide to use the ballot box as a vehicle for the realisation of the better tomorrow they have been clamouring for, 2023 may just be a replay of the Kenyan feat. Water may run uphill.

(Wole Olaoye is a Public Relations consultant and veteran journalist. He can be reached on [email protected], Twitter: @wole_olaoye; Instagram: woleola2021)