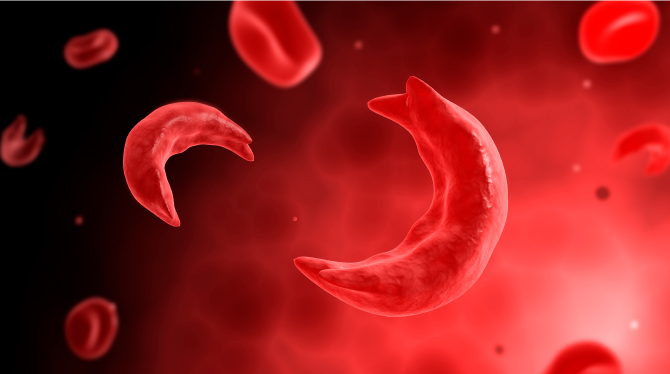

Born with sickle cell disease, Jimi Olaghere endured 35 years of excruciating pain crises, hospitalisations, and restrictions, until gene therapy changed everything. His story is more than a personal victory. It is a glimpse into a future where sickle cell disease may no longer be a life sentence in Nigeria.

Olaghere, a 39-year-old Nigerian, is one of the first people in the world to be cured of sickle cell through a CRISPR gene-editing trial in the United States. He said, “I lived with sickle cell disease for 35 years, pain crises, hospitalisations, and limitations. After undergoing gene therapy, I am now crisis-free, pain-free. It’s like having a second life. Coming home to Nigeria to share this story means everything to me,” he said.

Olaghere’s emotional testimony drew attention to the contrast in healthcare access between developed nations and Nigeria. Born in the U.S. after his mother traveled there for prenatal screening, he later joined a gene therapy clinical trial that transformed his health.

“I’ve shared my story around the world, but this, coming back to Nigeria, is the most important destination. This is where the story truly matters,” he said.

An estimated 150,000 babies are born with sickle cell disease every year in Nigeria, accounting for nearly half of the global burden. Despite decades of awareness efforts, many patients still grapple with limited access to basic care, let alone advanced therapies. For many families, the disease continues to mean missed school days, lost income, chronic pain, and emotional exhaustion.

It is against this backdrop that the 5th Global Congress on Sickle Cell Disease held in Abuja, brought together over 60 countries with diverse group of stakeholders including healthcare professionals, researchers, caregivers, patients, advocates, policymakers, and industry leaders, with one goal: to move curative therapies, particularly gene therapy and bone marrow transplantation, from hope to reality in Nigeria.

Gene therapy is offering new possibilities to people who have long lived with SCD painful and often life-threatening complications. But the treatment comes with challenges, medical, financial, and structural, that mean it is not yet an option for everyone who needs it.

A faculty member at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School and co-founder of the Global Gene Therapy Initiative, Prof. Jennifer Adair, said the issue isn’t whether gene therapy works, it’s who gets access.

“As a researcher, I realised early that we were not doing enough to make these therapies accessible to all people who need them,” she said.

In 2020, her initiative began engaging countries that wanted to adopt gene therapy. Six nations have already joined, with Nigeria among them. “We support local networks of scientists, doctors, patients, and policymakers who want to find their own solutions. This can’t be imposed from outside. It must be built from within,” she said.

She cited progress in Uganda, where a bone marrow transplant bill was passed, a regulatory framework for gene editing is underway, and local manufacturing is being considered to drive down costs.

One of the biggest barriers to gene therapy remains its cost, up to $2.2 million per patient in the U.S. But Adair insisted this price tag is not fixed.

“In Uganda, we developed a cost-effectiveness strategy. The same therapy Jimi received could be viable there at about $40,000. That’s still high, but much more scalable,” she noted.

Further cost reductions are possible through local manufacturing. She highlighted the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India, which produces a similar therapy for cancer patients at about $35,000 per treatment.

“If governments invest in local production, gene therapy could become not only possible but sustainable,” she said.

Adair also revealed ongoing efforts to train Nigerian scientists and clinicians. Some have already visited India for hands-on learning. The Global Gene Therapy Initiative is working on providing educational materials in local languages and pushing for early knowledge transfer before gene therapies become fully commercialised.

A former President of the American Society of Hematology and Chief of Hematology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Dr. Alexis Thompson, who has been at the forefront of research and treatment in this area, described gene therapy as “extraordinary.”

She, however, pointed out that it is a complex medical procedure, with real and sometimes serious risks.

“Some of the risks that are associated with gene therapy are the same as those seen with other forms of stem cell transplants,” Dr. Thompson explained. These can include temporary side effects like hair loss, mouth sores, and an increased risk of infection or bleeding, often due to the chemotherapy used to prepare the body for the procedure. Less common complications include liver or lung issues, and in some cases, the possibility of infertility.

For patients who have not yet had children, fertility preservation is often recommended. “We usually advise people to store eggs or sperm before starting treatment,” she said.

Despite these risks, many patients with sickle cell disease choose to proceed. For those living with chronic pain, frequent hospital visits, or complications like stroke and acute chest syndrome, gene therapy can offer a real chance at a better quality of life. “Many of my patients have lived through experiences that are incredibly difficult. For some, the decision to try gene therapy is not a hard one,” she said.

Not every sickle cell patient is currently eligible for gene therapy. Clinical trials to date have mainly included patients between the ages of 12 and 35, and most have had either the SS genotype or a severe subtype called S beta zero thalassemia. This doesn’t mean other forms of the disease, such as SC genotype, won’t benefit, it’s just that they haven’t been the focus of research so far, she said.

“We expect that patients with SC disease will benefit too, just as they do from other forms of transplant. But that still needs to be studied further,” Dr. Thompson said.

As promising as gene therapy is, access remains limited. Many patients have had to travel long distances to receive the treatment, sometimes even across continents. Dr. Thompson believes that must change. “We need to figure out how to deliver this treatment closer to where people live. That’s the only way it will truly become accessible,” she said.

The good news is that the therapy’s success rates are encouraging. Between 90 – 94 per cent of patients treated so far have remained free of sickle cell pain for long periods. “The first patient I treated with this approach is now 11 years post-treatment and has been healthy the entire time,” Dr. Thompson shared.

However, gene therapy is still evolving. Researchers are already exploring ways to make the process simpler, safer, and more affordable. While it may not yet be the solution for everyone living with sickle cell disease, it is a step forward and one that could become more widely available with the right support and planning.

Nigeria, home to the highest number of people living with sickle cell globally, has a critical role to play in that future. The special adviser on Sickle Cell to the Coordinating Minister of Health and Chair of the Local Organising Committee (LOC), revealed that an estimated four million Nigerians are currently living with SCD. This figure, she said, is based on the 2018 National Demographic Health Survey, which reported that between 1.5 to 3 per cent of Nigerians across the geopolitical zones are affected by the disorder.

“Sickle cell disease is not just a national issue; it’s a global health challenge,” Nnodu said, citing the World Health Organisation’s estimate of 7.7 million people affected worldwide. “Nigeria carries a significant portion of this burden, and this congress is a critical platform to spotlight solutions, drive innovation, and foster global collaboration in managing and ultimately eradicating the disease.”

Nnodu stressed the importance of policy reform, legislative backing, and unified NGO action to amplify the sickle cell advocacy agenda both within Nigeria and across the continent. “We need to work under one umbrella to achieve a voice louder and stronger than our individual efforts,” she stated.

The road ahead involves more than just scientific breakthroughs. It will take political will, strategic investment, collaboration, and a commitment to ensuring that no one is left behind.