The poor state of the national library was the subject of a public outcry by the chief executive officer of the National Library of Nigeria, Professor Veronica Chinwe Anunobi. For a public official who is rarely in the news, the alarm about the library’s state should attract more than a passing interest.

At an annual press conference, she said the apex library and Nigeria’s documented heritage, preserved in the National Repository of Nigeria, are under threat.

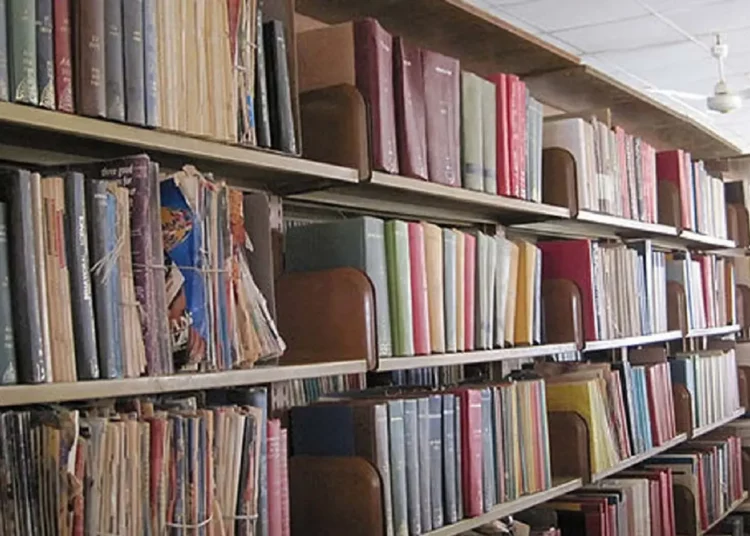

She listed the issues as including the absence of a permanent headquarters, the dilapidated state of resources (newspapers, journals, and book publications) housed in the space-deficient National Repository of Nigeria, inadequate staff, and a low budgetary allocation incapable of supporting virtualisation.

READ ALSO: Nigeria’s Heritage, National Library Under Threat – Librarian

The same concern was conveyed at the 2024 conference of the national librarian with state librarians in Bauchi State, where the Nigeria Libraries Association (NLA), chairman Vincent Giwa Franklin said, “Most of our public libraries lack modern equipment and facilities” and that many are burdened with “outdated reading resources, books, and journals.”

He expressed one of the root causes of the crisis when he asserted that librarians are often not regarded as professionals in the public service.

Indeed, the cry for help over the state of the national library is one of many about the near total neglect of the education system and, more grievously, the seemingly willful disregard of human resources.

For decades, the education system has suffered a free fall in substance and structure, from corruption to incapacity and poor allocation to the sector. Children of the elite bag degrees in ultra-expensive primary and secondary institutions and foreign tertiary schools largely funded by the commonwealth while the wards of the less-privileged are left to their own devices.

It is no surprise that Nigeria’s education sector has been deprived of effective public libraries. And for people who are quickly losing their reading culture, it’s to be expected.

Most public libraries are inadequate, featuring unwelcoming environments, old furniture, and collections of first or second editions of books from the 1960s and 70s. The reading rooms are often dark and stuffy, suffering from power outages and malfunctioning, and in most cases, there are no cooling systems.

In the distant past, students frequented libraries after school to access textbooks and reference materials crucial for examination preparation and personal development. Today, however, the reverse is the case as insufficient funding, poor management, government neglect, and the appointment of non-librarians to library boards have severely undermined public libraries.

It’s no surprise that the reading culture is in decline. Students opt for shortcuts to success, while those eager to study become discouraged by the lack of resources.

Libraries do more than meet individuals’ informational needs; they also foster civic responsibility and encourage productive leisure time use. They empower students to engage in lifelong learning and stay informed about various fields and global issues.

Regrettably, the rise of social media has further eroded this culture, as students prioritise internet activities—chatting, gaming, or streaming—over utilising available educational resources. The consequences are evident in the widespread failure in examinations.

This issue presents significant challenges for Nigerian higher education, with institutions producing graduates often labelled unemployable. The government and all stakeholders now have the responsibility to revamp public libraries to avert their collapse and improve academic performance linked to the deteriorating reading culture.

Public libraries need to be stocked with current and relevant materials. In collaboration with professional organisations, the government should establish virtual libraries in every local government area. Individuals, corporations, and educational foundations that manage private libraries or contribute books to schools should be encouraged to enhance their efforts. Together, we can modernise libraries to tackle the issues of mass failure and revitalise society’s reading culture.

From this perspective, we welcome the establishment of the National Assembly Library, which was inaugurated last year. It’s a good feat. We, however, hope that the lawmakers, who have shown some positive inclination towards the library sector, will extend their attention to the national library.

Such attention would start by heeding stakeholders’ calls and making the most of what they have called for a reality. All that is required is the commitment of the government and the professionals. We are also persuaded to remind the lawmakers that the National Assembly Library must not be treated as a replacement for the National Library. We expect them to allocate resources very much needed for the development of that vital national outfit.