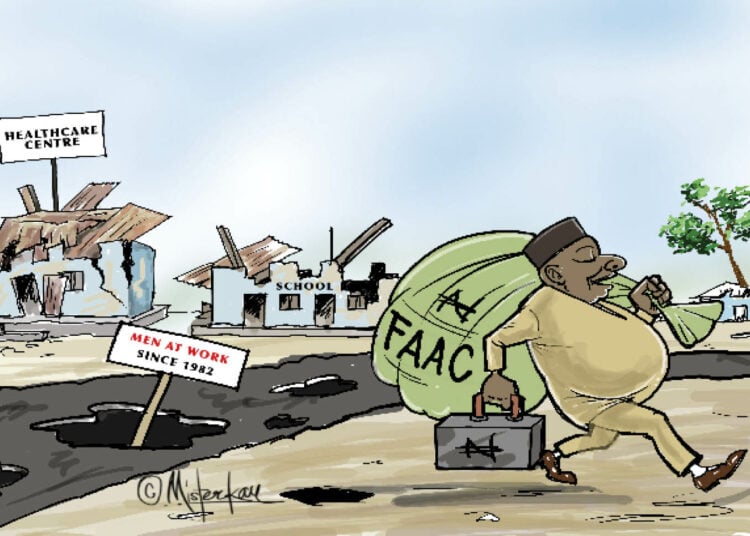

In 1999, shortly after Nigeria’s return to democracy, a senior bureaucrat in one of the northern states told a journalist, “Once the federal allocation comes, governance is complete.” He wasn’t joking. The monthly federal allocation, the famous “FAAC”, was treated not as a means to govern, but as an end in itself. Roads could crumble, schools could rot, hospitals could remain mere structures, but as long as salaries were paid and a few projects commissioned before elections, the illusion of governance endured.

Two and a half decades later, that illusion is being challenged. Not by slogans or press releases, but by data – comprehensive, verifiable, citizen-informed data. The 2025 Phillips Consulting State Performance Index (pSPI) has arrived, and with it, a long-overdue mirror held up to Nigeria’s 36 states and the FCT. It shows, with elegant simplicity, who is doing the hard work of governance – and who is coasting on excuses and federal largesse.

What sets the pSPI apart is not just the volume of information it carries, but the weight of truth it holds. Drawing on 70% objective data and 30% citizen perception, the index gives a score that is both technical and experiential. In other words, it doesn’t just count what governments say they’ve done, it also captures what citizens feel they’ve received.

The results are illuminating, if occasionally unsettling. Lagos, Ogun, and Kaduna topped the charts, buoyed by strong internal revenues, capital expenditure, and infrastructure. Meanwhile, states like Adamawa, Abia, and Niger rose sharply through the rankings, proof that political will, not just resources, makes the difference. On the other hand, Bayelsa, Kogi, and the Federal Capital Territory suffered significant declines or exclusions, raising difficult questions about transparency and ambition, or the lack thereof.

The Top Three: Numbers Over Noise

Lagos came first overall, despite being 32nd in citizen perception. How? By excelling in the hard, unsexy work of governance: generating revenue, building infrastructure, managing debt, and planning urban growth. Lagos is not perfect, its residents are frustrated by traffic, cost of living, and sometimes opaque policies. But the machinery works. It delivers.

Ogun State, in second place, quietly strengthened its business environment and public infrastructure while also climbing the ladder of digital governance. Kaduna, in third, continues to reap the fruits of reforms in education, public service, and data systems. These states are not without their critics, but their commitment to planning and performance is reflected in their pSPI scores.

Consider the story of a mid-level trader in Abeokuta who, for the first time, received a digital property registration certificate in under two weeks. “I was shocked,” he said, “because before, you could wait six months or even a year. Now, it’s as if they want you to succeed.” Anecdotes like this speak volumes. They are what metrics like “ease of doing business” try to quantify, and what the pSPI brings into focus.

The Surprise Climbers: Will Over Wealth

Perhaps more impressive than the high performers are the dramatic risers. Adamawa jumped from 26th to 4th. Abia rose from the very bottom, 36th, to 10th. Niger climbed from 29th to 5th. These states are not known for oil wealth or megacities. What they have in common is leadership that decided business as usual would no longer suffice.

In Abia, reforms in transparency and local government engagement helped shift public perception and improved objective outcomes. A civil servant there recounted how monthly salary alerts became regular for the first time in years. “Before, we’d beg, strike, and protest,” she said. “Now, things feel more stable. You can plan.” That simple act, consistency in salary, can transform the legitimacy of a government in the eyes of its people.

Adamawa focused on rebuilding key infrastructure and improving public sector accountability. Niger improved its fiscal management and capital expenditure, even while dealing with security concerns. These are not minor tweaks. They represent a change in mindset: that even with limited means, it is possible to govern with purpose.

The Fall of the Complacent

But while some states are rising, others are falling, and fast. The FCT, once among the top five, was dropped from the rankings entirely because it failed to publish audited financials. For the capital of a nation, that is more than an administrative oversight; it is a moral failure. Transparency is the bare minimum of governance. Without it, there can be no credibility.

Bayelsa, which ranked 6th last year, plummeted to 29th. Kogi came in at 35th. In these cases, the problems are structural and behavioural. Low internally generated revenue, weak infrastructure, poor citizen satisfaction, and lack of strategic planning all converged to produce these dismal outcomes.

A doctor in Yenagoa told a story that haunts the heart. “We have incubators,” she said, “but no power. Babies die, and we call it fate. But it’s failure.” These failures are not abstract. They are not captured in grand speeches. But they show up in the pSPI – in low health infrastructure scores, in poor capital expenditure, in citizen dissatisfaction. And they demand answers.

Why the Methodology Matters

The strength of the pSPI lies in its method. Its 37 indicators cover fiscal strength, service delivery, social wellbeing, business environment, and latent potential. These indicators are standardised so that smaller states are not penalised for size, nor richer states rewarded merely for income.

The use of ratio-based benchmarks – IGR per capita, debt per square kilometre, healthcare access per thousand residents – ensures that states are measured against themselves and each other in fair and comparable ways.

Just as important is the perception data. 9,498 Nigerians across all regions shared how they experience their states. Less than 30% believe they get value for the taxes they pay. More than two-thirds don’t know who their local government chairman is. In many states, over 80% have no idea what projects are being executed in their communities. These are not just numbers; they are a referendum on the distance between government and the governed.

A Federation Demanding Competition

The real power of the pSPI lies in the cultural shift it encourages: from entitlement to competition. Nigeria’s federalism has often rewarded underperformance. States receive funds regardless of outcomes. The pSPI flips that script. It invites states to compete—not for applause, but for impact.

There is a lesson here for development partners, investors, and even citizens. Use the pSPI as a lens. Ask your governors why they rank where they do. Ask why neighbouring states are doing better – or worse. Ask what changed between 2024 and 2025. The answers will reveal not just governance quality but future potential.

Earning Autonomy, Not Demanding It

Federalism is a gift, but it must be earned. The pSPI doesn’t hand out medals. It offers mirrors. It shows that some states, with less money and more constraints, are outperforming richer peers. It proves that citizens are watching – and speaking. It demonstrates that data, when used properly, can become the most powerful accountability tool in the republic.

Nigeria’s states must take the pSPI seriously, not because it flatters or exposes them, but because it forces them to do what democracy demands: justify their mandate. In this mirror, there is no hiding. Only truth. Only results. Only responsibility.