February 18, 1897 is a date Nigeria and the Benin people will never forget. It was a day of horror and gloom as the British invaded the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin. They murdered and pillaged; hence the Benin kingdom has never been the same since the British desecration. History shows that the 19th century witnessed the infamous Scramble and Partition of Africa by European powers and the invasion of the Benin Empire was only a matter of time.

On that day, a large British military force arrived in Benin City under orders to invade and conquer. They came with an arsenal that included canons and advanced weaponry. They were met with Benin fighters with their crude Dane guns and spears; obviously, the Nigerians stood no chance. In time the British overran them and captured Oba Ovonramwen, the sitting monarch, sending him into exile in Calabar. The daily routines of the royal court were subsequently disrupted and the Edo people were severed from their leaders.

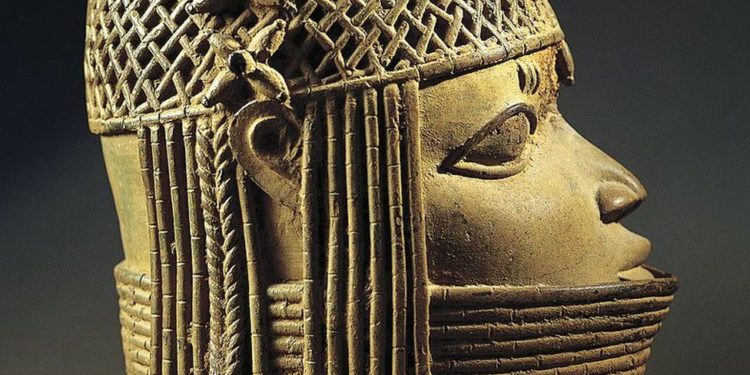

The Benin kingdom was and is still known for its ingenious art works and artifacts and the palace housed many of these wonders. After the invasion, many of the arts and artifacts within the royal palaces were now the spoils of war, many of which were sold to defray the costs of the invasion by the British. Others were shared among members of the expeditionary force. Still others left Benin in the confusion that followed the devastation of the kingdom.

Upon their arrival in London, they looted art and artifacts sparked immediate interest from wealthy collectors and museums, particularly in Britain and the German-speaking world. There was an unprecedented scramble for them from art enthusiasts with their voracious appetite or any art. They all made efforts to purchase the objects for their collections. Eventually the artifacts from Benin found their way to shelves and display cabinets in museums and private collectors across Europe and the United States. They still sit there today.

A salient development is happening though. For some years now, Nigeria has been witnessing stolen arts and artifacts being returned to the rightful owners. In particular, some of the artifacts stolen from the Benin Kingdom during the invasion are being returned by Europe, albeit gradually. This of course is happening over 120 years after the pillaging and outright theft of these artifacts.

Just recently, Germany and Nigeria signed an agreement that paves the way for the return of hundreds of Benin Bronzes – an accord that Nigerian officials hope will prompt other countries to follow suit. Hundreds of the Benin Bronzes were sold to collections such as the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, which has one of the world’s largest groups of historical objects from the Kingdom of Benin, estimated to include about 530 items, including 440 bronzes. Many of them date from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

However, even if Germany were to return all of the Benin objects in Berlin, this would not amount to much more than 10 per cent of what was looted. To be sure, other museums will follow, or even play at leading the returns, such as museums in the German cities of Stuttgart or Cologne. However, other big museums outside Germany are slow to follow. Colonialism was a European project and so was the looting of African art and artifacts. So, all of Europe, all of the Global North are implicated and need to address this issue.

The most important collection of the looted Benin artifacts with up to 800 of them is in the British Museum in London, which, apparently with the support of the government, has categorically denied the need for restitution. This ties in with a larger debate about taking responsibility for colonialism as a crime against humanity. The Global North is slowly conceding that there were acts of violence within colonialism but still shy away from the atrocities they committed during the period.

Also, while the Benin bronzes are some of Africa’s greatest treasures, they tell a story of colonial violence which was predominant in Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. Colonialism was all about control and the European colonizers used and justified violence against their colonized subjects. Wherever, imposing colonial control was often bloody for several reasons. Whether European, or American, colonial powers usually had modern weapons that were far deadlier than what the locals had. This was the case in the British invasion of the Benin Kingdom.

The infamous Scramble for Africa in which 14 European powers voraciously supped around the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference table is a haunting and living legacy that still echoes across the African continent. Since the Conference preceded the invasion of Benin by over a decade, it might appear accidental – or fortuitous. Likewise, since the conference was held over 130 years ago the social, economic and political instabilities associated with these states might suggest some natural inability to self-govern. Clearly this would be an ill-conceived perspective ignoring the deliberate and lasting impact of the Scramble.

There is currently an Edo Museum of West African Art being built in Benin City, Edo State, which should be hosting the returned Benin bronzes and artifacts. How exactly the returned artwork is distributed between Nigeria as a nation state, Edo state as a federal entity and the Oba of Benin – as heir of the former kingdom and representative of the Edo people – is still a matter of discussion. Frankly, however, this is not the Europeans’ concern. What the rightful owners do with their art is their decision, and this must not delay restitution.

A major question that has popped up with the return of these artifacts is perhaps the ever-running Nigerian question, can we maintain them? Do we have the resources to make our museums run at a profit for them? Will people be willing to go all the way to Benin to see these artifacts? Should leaving the artifacts in European museums be a consideration is Nigeria is going to get paid and the treasure troves maintained and protected? One knows the security situation and the reality of the maintenance culture in Nigeria.

No doubt the Nigerian government is on the right side of nation-building and recognizes the value of storing historical artifacts at home. For Nigeria to maintain these artifacts, she needs well built and maintained museums in peaceful areas where the risk of insecurity can be neutralized with ease. It needs a population that has the disposable income to visit and fund the museums, and also, the educational interest to boost relative studies on the impact of the artifacts in West African art, politics and history.

Perhaps economically, the artifacts might just be better off in European Museums who pay annual royalties to the Nigerian government to maintain them. However, from a nation-building perspective, their non-return would be a Cultural own-goal as Nigeria will lose out on the key input needed to boost the local tourism industry.

The Nigerian government needs to continue the push for the return of, not only the Benin bronzes and artifacts, but also artifacts of the Oyo Empire and Nok culture that is attracting tourists in several museums abroad and generating income for these countries.