In the lexicon of African political science, few concepts have endured with such explanatory power as “prebendalism”—a system in which elected officials and bureaucrats consider public office as a means of acquiring personal wealth and distributing state resources to their ethnic, religious, or political networks. Coined by political scientist Richard Joseph in 1987, the term captures a peculiarly persistent pathology of governance in many postcolonial states, particularly Nigeria. It is both an economic system of appropriation and a political culture that normalises patronage and nepotism as legitimate forms of statecraft.

Four decades later, Nigeria and many other African states remain ensnared in the grip of prebendal logic. While democratic institutions have been established and elections are regularly held, the essence of democracy —transparency, accountability, the rule of law, and a commitment to the public good —remains elusive. This gap between form and substance has become the Achilles’ heel of African governance. And at its heart lies the corrosive legacy of prebendalism.

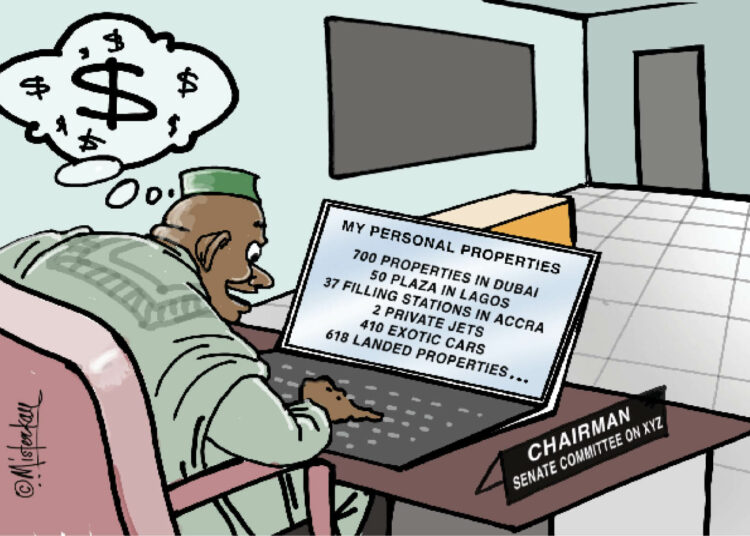

In prebendal systems, political competition is not about policies or ideologies but access to state coffers. Political offices, governorships, legislative seats and ministerial portfolios, are pursued as investment opportunities, with the expectation that those who attain them will “recoup” their investment through rent-seeking and clientelist distribution. The public treasury becomes an ATM for personal enrichment and political loyalty-building.

In this setup, merit becomes secondary to loyalty, and state resources are weaponised for political survival. Procurement contracts are inflated to provide kickbacks. Infrastructure projects are abandoned midstream, often serving as vehicles for siphoning funds rather than delivering public goods. Recruitment into the civil service is distorted by ethnic quotas and political patronage, stifling competence and professionalism.

Thus, the political class becomes less a steward of national interest and more a cartel of elite rent-seekers, insulated from the daily struggles of citizens. Elections become high-stakes battles not for ideological supremacy but for control of distribution networks. Governance becomes burdened not by the complexities of policymaking, but by the imperative to “settle” supporters, allies, and “godfathers.”

Democracy Under Siege

The burden of democratic governance under prebendal conditions is profound. First, the legitimacy of democratic institutions is eroded. When elections are perceived as gateways to looting rather than service, voter apathy grows, and trust in democracy declines. Citizens begin to see government not as a collective endeavour but as a hostile, extractive force, something to avoid or exploit, not reform or engage.

Second, democratic accountability is weakened. In a prebendal system, accountability flows upward—to patrons—not downward to the electorate. Legislators are more beholden to party financiers than constituents. Civil servants are more loyal to the political class than to the constitution. The media, civil society, and watchdog institutions are often underfunded, co-opted, or repressed, making it difficult to expose malfeasance or demand redress.

Third, policymaking is shallow and inconsistent. Long-term planning gives way to short-term political expediency. Reform initiatives are often stillborn, blocked by entrenched interests or sacrificed on the altar of political convenience. Even when good policies are formulated, their implementation is frustrated by institutional decay and lack of political will.

Fourth, corruption becomes normalised. It is not simply tolerated but expected. The question is not whether a public official is corrupt, but whether they “shared” the loot equitably. Anti-corruption campaigns are often selective, targeting opponents while shielding allies. Over time, public cynicism sets in. When the system is rigged and justice is elusive, citizens lose faith in democratic ideals.

The Human Cost of Prebendalism

The economic and social costs of prebendalism are staggering. Essential services like education, healthcare and infrastructure, are chronically underfunded and poorly delivered. Youth unemployment skyrockets as job opportunities are reserved for those with the right “connections.” National productivity stagnates as corruption and misgovernance discourage investment and innovation.

In Nigeria, for instance, despite decades of oil wealth and democratic rule since 1999, poverty remains endemic. Over 60% of the population lives below the poverty line. The public education system is in disrepair, with frequent strikes and infrastructural collapse. Health indicators are abysmal, with high maternal and infant mortality rates. And insecurity, especially the triple threats of banditry, terrorism, communal clashes, has metastasised, in part because state institutions lack both capacity and legitimacy.

These are not just technical failures; they are moral and political failures. They reflect a profound betrayal of the democratic promise. Prebendalism converts public trust into private gain and reduces citizenship to clientelism. It creates a predatory elite and a disempowered populace. It is, in the final analysis, antithetical to the democratic project.

Pathways to Reform and Democratic Reckoning

Escaping the stranglehold of prebendalism requires more than technocratic fixes. It demands a wholesale reimagining of politics, governance, and civic culture.

Starting with political and electoral reform, democracy must be made more transparent, competitive, and participatory. This includes reforming electoral commissions to ensure independence, enforcing campaign finance regulations, and curbing the influence of “godfathers” and money politics. Electoral processes must be credible and reflect the will of the people. Internal party democracy must be strengthened to break the stranglehold of elite cabals.

Then, institutional strengthening with key state institutions including the judiciary, civil service, anti-corruption agencies intentionally insulated from political interference and professionalised. Appointments should be based on merit, not patronage. Institutions must be equipped to resist political capture and enforce accountability impartially.

Also, civil society, media, and citizens must play a more assertive role in demanding good governance. Civic education should be mainstreamed to deepen public understanding of rights, responsibilities, and the workings of government. Grassroots organising, social movements, and digital activism can amplify citizen voices and hold leaders accountable.

Ultimately, political culture is shaped by leadership, so leadership transformation is equally critical. A new generation of leaders must emerge, leaders driven not by the lure of office but by a commitment to service, ethics, and nation-building. Such leadership must be cultivated through mentorship, political education, and institutional incentives that reward integrity.

Finally, there must be conscious efforts towards decentralisation and resource equity. Over-centralisation of power at the federal level fuels prebendalism by making access to the centre disproportionately valuable. A more equitable and transparent system of resource allocation, coupled with genuine devolution of powers, can help reduce the stakes of central politics and improve local accountability.

Prebendalism is not merely a political flaw; it is a moral crisis. And yet, the endurance of this system is not inevitable. Across Africa, courageous individuals, reform-minded politicians, principled civil servants, and mobilised citizens are challenging the status quo. From anti-corruption protests to grassroots campaigns for electoral integrity, the struggle for accountable governance continues.

But this struggle is uphill and urgent. As poverty, insecurity, and inequality deepen, the state’s capacity to deliver on democratic dividends is increasingly questioned. If prebendalism remains unchecked, democracy itself may lose its legitimacy in the eyes of citizens. The result will not be the return of military rule, perhaps, but the entrenchment of authoritarian populism, illiberal democracy, or state failure.

The burden of democratic governance is heavy, not because democracy is inherently flawed, but because its promise has been hijacked by those who see public service as private entitlement. It is time to break this cycle. The task before us is not only to elect leaders but to transform the political culture; not only to build institutions but to uphold the values that make democracy meaningful and redeem the democratic promise of June 12.