Imagine reading a book with no way to turn back the page. How carefully would you read it?

That is the question Nigeria, and indeed Nigerians must confront today, not in metaphor but in its bones. For over six decades, the country has read its own history too quickly, skipped past its tragedies, misread its triumphs, and often mistaken mere survival for success. History has offered countless warnings – Greece, Rome, Carthage, Songhai, Mali, even Oyo and Benin – of what happens when power concentrates without accountability, when institutions are hollowed by corruption, and when the center no longer holds. Nigeria has not only ignored these parables; it has rewritten them into farce. But history is not sentimental. And as Thucydides reminded us in The History of the Peloponnesian War, “It is the habit of all men… to give way to their passions.”

Foundations Built on Compromise and Clay

At independence in 1960, Nigeria did not begin with a clean slate. It began, rather, like Rome after Caesar’s assassination – fractured, anxious, burdened by the expectations of freedom, but unsure how to wield it. The British colonialists, in classic imperial fashion, left behind a state held together by administrative convenience rather than organic consensus. Much like the fragile Peace of Nicias in ancient Athens, the independence settlement was an uneasy truce, not a durable union.

Nigeria’s three regions – North, West, and East – were cultural empires in their own right. But instead of a confederation of equals, the new republic became a battlefield of factions. The First Republic mimicked the doomed Athenian democracy where orators inflamed mobs, corruption undermined virtue, and ambition trumped wisdom. Regional parties, ethno-political alliances, and opportunistic coups replaced the deliberative governance imagined at independence. Like the Roman Senate that watched helplessly as the Republic slipped into imperial dictatorship, Nigeria’s institutions stood by as soldiers replaced statesmen. By 1966, the book’s early chapters had already been marred with blood.

War Without Reckoning, Peace Without Justice

Between 1967 and 1970, Nigeria wrote its darkest chapter in the Civil War – a war that, like Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon, could have been avoided but not reversed. The causes of the war were layered: a botched federal structure, ethnoreligious massacres in the North, a failed effort at confederation in Aburi, and a brutal assertion of state sovereignty.

Over one million people, most of them Igbos, died. It was a war of attrition, blockade, and starvation, evoking echoes of Carthage under Roman siege. And yet, when Biafra surrendered, there was no reconstruction of the soul of the nation. “No victor, no vanquished” was declared, but no real reconciliation followed. No national truth commission. No constitutional reform to address the causes of war. The East was left to rebuild itself, emotionally and economically, with little institutional support. Nigeria chose amnesia over reckoning. Like the defeated Greeks after Thermopylae, the Igbos were expected to rejoin the empire with pride swallowed and wounds unhealed.

The post-war years brought oil wealth – a new golden calf. But unlike King Solomon, who asked for wisdom to rule a vast and diverse kingdom, Nigeria’s leaders asked for nothing but more oil.

The Curse of Black Gold

Oil was supposed to be Nigeria’s deliverance, as it was for Iraq, Libya, and Venezuela. But like the gold of Midas, it turned all it touched to rot. From the mid-1970s onward, Nigeria became a classic rentier state. Its leaders, like Nero fiddling while Rome burned, danced through the streets of Lagos while rural schools collapsed and hospitals decayed.

General Yakubu Gowon, flush with petrodollars, declared that Nigeria’s problem was not money but how to spend it. By the time Shehu Shagari was elected in 1979, Nigeria had the infrastructure of a middle-income country and the governance of a failing state. From Obasanjo’s military regime to Buhari’s first coming, the military entrenched itself not just in barracks but in banks, ministries, and contracts.

Like the Byzantines, whose empire survived on ceremony long after it lost its soul, Nigeria developed the rituals of state without the substance of governance. Constitutions were written, torn, rewritten, and manipulated – never through popular consensus, but through backroom drafting by soldiers in epaulettes and judges in silence.

Meanwhile, the Niger Delta, source of the oil, became its poisoned well. Ogoni protests, the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa, and the rise of militant groups echoed the rebellion of Rome’s provinces when taxed and exploited without representation. Abuja – the city built as a symbol of unity – became a fortress of entitlement, floating above the discontent of the people.

Democracy Without Accountability, Power Without Progress

When democracy returned in 1999, the country exhaled, but cautiously. Like post-World War II Europe rebuilding from ruins, Nigeria’s democratic architects inherited wreckage. Yet unlike the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe through investment and reform, Nigeria’s return to civilian rule merely restored old elites in civilian clothing. The 1999 Constitution, hurriedly compiled by the outgoing military regime, was neither federal nor participatory. It preserved centralized control, sidelined local governance, and codified mediocrity through federal character.

Elections have since been conducted, but the process resembles more the spectacle of Roman gladiator games than genuine civic contest. Votes are cast in fear. Results are litigated, not accepted. Courts are weapons, not arbiters. Political parties lack ideologies – only ethno-geographic arithmetic. The zoning principle, a crude form of rotational power-sharing, is a desperate attempt to maintain balance, like the Roman Tetrarchy. It treats unity as appeasement, not shared vision.

The #EndSARS protests of 2020 were a warning – a civic eruption, youthful, spontaneous, and pan-Nigerian. But like the revolts of the Gracchi brothers in ancient Rome, they were crushed swiftly and violently. The Lekki Toll Gate shootings were not just a massacre – they were a message: the state remains above the citizen. No inquiry has restored trust since. The lesson was clear: this democracy was never built for accountability. It was built for survival. And survival, unanchored by justice, is tyranny with better branding.

The Hourglass Has Thinned

Now, Nigeria stands not at a crossroads – but at a precipice. The signs are familiar to anyone who reads history. Bread prices rising. Young people leaving. Confidence collapsing. Armed groups expanding. Institutions retreating. Trust evaporating.

The poet Virgil, writing in the wake of Rome’s civil wars, lamented: “We cannot endure our vices, nor their cure.” That is Nigeria’s affliction today. The cost of reform is high, but the cost of inertia is higher. Ethnic mistrust, once underground, now shouts from podiums. Religious intolerance, once whispered, now arms itself. Political exclusion, once deniable, now defines entire regions. Youth unemployment exceeds fifty percent. Yet elections continue to produce familiar faces, familiar failures.

No country survives forever on potential. Sparta had discipline. Athens had intellect. Rome had law. Carthage had trade. All fell – not from weakness alone – but from denial, decay, and delay. They fell one choice too late.

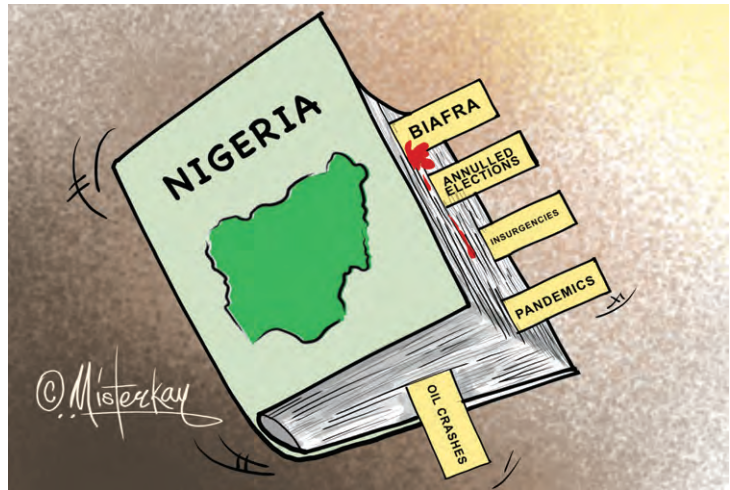

Nigeria has been given chance after chance. Biafra, annulled elections, insurgencies, pandemics, oil crashes – each should have sparked a reckoning. But instead, the ruling class turns the page as if nothing happened. They forget that the book has an ending – and readers remember.