Dear Wole Olaoye,

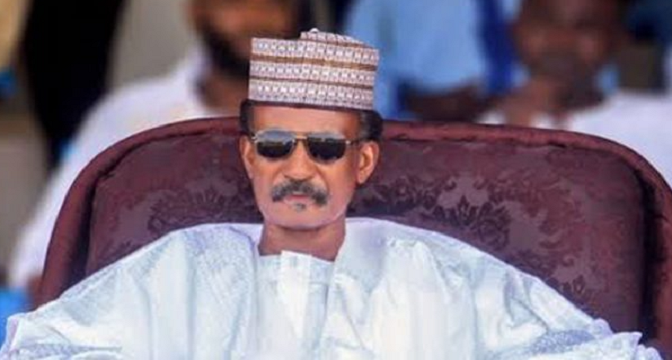

I refer to your tribute in the LEADERSHIP Sunday of October 13, 2024 to Colonel Abubakar Dangiwa Umar (rtd) on the occasion of his 75th birthday in September. In the well-deserved tribute, you mentioned two things he did which, in your opinion, “stood (him) out as an officer and gentleman with an eye on history.”

The first was the position he took on an issue in which you said the late Innocent Oparadike, as Editor of New Nigerian, petitioned the Newspaper Proprietors Association of Nigeria (NPAN), then meeting in Kaduna, about his predicament in trying to assert his independence. At that time, Dangiwa was the military governor of the old Kaduna State which included the present Katsina State and which was the host state of the newspaper.

You did not mention the date, but this was in March 1987 following the outbreak of religious riots between Muslim and Christian students of the Kafanchan College of Education, in the state. The college was, at that time, playing host to the year’s annual evangelical circuit of “born again” Christian students’ movement. The trigger was an alleged misinterpretation of the Qur’an by one Abubakar Bako, a lay Christian preacher and Research Fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Research, Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria. Some Muslim students, irked by what they apparently regarded as blasphemy against their holy book, took the law into their hands and attacked Bako and his audience. Predictably, the ensuing bloody clash got out of hand and soon spread well beyond Kafanchan.

Oparadike’s predicament as editor arose, you said, because articles on issues, presumably including the Kafanchan riot, were often written “by faceless and narrow-minded persons (and) passed over his head, straight to production.” Oparadike, you said, petitioned NPAN to protest being forced to sign off the newspaper “as if he had seen and endorsed every item therein.” The NPAN, you said, in turn, tabled the matter before Dangiwa to seek reprieve for Oparadike. Dangiwa’s solution, you said, was that NPAN should tell Oparadike “to be a man and challenge those intruders. It is only then that he can earn their respect.”

The import of your story was that, contrary to the general expectations because of his pedigree as a Northern aristocrat, Dangiwa stood for what was right by an editor and against the powerful “faceless and narrow-minded persons” who tried to dictate what the New Nigerian published.

Dangiwa was right to have stood by Oparadike as editor, if indeed the NPAN tabled his case before him. However, the problem with your story was that there was never, repeat never, any article, including about the 1987 Kafanchan religious riots, which did not pass the journalistic tests of fairness, balance and objectivity that was foisted on Oparadike. I know because I was the managing director of the newspaper at the time. However, before I explain how, let me talk a bit about the second thing which you said stood Dangiwa out as a gentleman and officer with an eye on history.

The retired Colonel, you said, was “the last soldier standing when General Babangida annulled the fairest election ever held in Nigeria.” Dangiwa demonstrated rare courage, you said, when he challenged his bosses to release the remaining results of the June 12, 1993 presidential election which Chief MKO Abiola, the candidate of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), seemed poised to win. And when his bosses ignored him, he took the rare principled step of resigning his commission, thus ending what was clearly a promising military career.

Dangiwa’s action was indeed courageous, risking as it did, not only his career but even his life because, as you pointed out, it could have led to his being court-martialled and possibly sentenced to death. However, courageous as he was, Dangiwa was not alone among prominent Northerners in opposing the annulment of the election. Even more prominent persons such as the late General Hassan Usman Katsina, a former army chief and the last governor of the North as a region, as well as the late Malam Adamu Ciroma, a former managing director of New Nigerian in its heydays, and whose putative victory as the presidential candidate of the National Republican Congress (NRC) was inexplicably annulled by Babangida to pave way for the second primary in which Abiola emerged as SDP’s candidate while the late Alhaji Bashir Tofa emerged as the NRC candidate, also spoke unequivocally against the annulment.

Malam Adamu, for example, was on record to have said Chief Abiola won the election “fair and square” and should be declared winner. In an interview with the rested Citizen magazine (June 21, 1993), he, among other things, said, “In this election, Chief Abiola has won. I believe that decency indicates that his NRC opponent should concede victory and congratulate him for the result.”

Malam Adamu’s interview was part of the edition’s lengthy cover story on June 12 which was critical not only of the suspension of the results of the election but generally of General Ibrahim Babangida’s rather elastic transition programme. In its lead editorial on the issue in the same edition, the magazine, which was co-founded by myself, the late Bilkisu Yusuf, the first and only woman editor of New Nigerian, Adamu Adamu, former President Muhammadu Buhari’s minister of education, and Kabiru Yusuf, chairman of Trust Media Ltd, said the authorities should uphold the result of the election. “In the name of all that is fair and just and in the name of peace and stability,” the magazine said, “we… must let the election be.”

All of this is not to detract from Dangiwa’s courage in standing up for June 12. Rather it is to debunk the widespread notion that the annulment of June 12 was some grand northern conspiracy to stop a southern politician from ever ruling this country, as was clearly implied in your claim that Abiola’s aborted victory as the first southern candidate to win a general election in the country “would have ushered in a truly national government not based on parochial provincialism.”

Back to Dangiwa’s stance on Oparadike’s grouse against some “faceless and narrow-minded persons” undermining his independence as editor of New Nigerian by forcing him to “sign off on the paper as if he had seen and endorsed every item therein.” As I’ve said earlier in this piece, I was its managing director at the time. But until I read your tribute to Dangiwa, I never knew that the association ever tabled Oparadike’s grouse before Dangiwa.

In doing so, fairness and equity demanded that, as the chief executive and therefore, the final word, at least in principle, on what it published, NPAN should have asked me the company’s side of the story.

This was more so because, as every journalist knows, editors don’t sign off their newspapers only when they see and endorse each and every one of the items for publication. They sign off mainly on the basis of consensus arrived at by line editors at editorial meetings, chaired by the editor, on the newsworthiness of items scheduled for the next edition of their publication. So, even without speaking with me, the NPAN, if indeed it tabled Oparadike’s claim before Dangiwa, should have known better than to believe his claim at face value.

However, whether the NPAN took up his case with Dangiwa or not, it was an open secret that Oparadike, as the first southerner to edit the New Nigerian following its takeover from the North by the federal government in 1974, came to the newspaper with an apparent mindset to make it difficult, if not impossible, for it to continue to speak for the North in the nation’s information order where the region and its predominantly Muslim population were already at a great disadvantage compared to the South.

Predictably, this mindset became a source of a long running battle between the two of us, a battle which some prominent members of NPAN, as individuals – notably, the late Dele Giwa, Ray Ekpu, Yakubu Mohammed and Dan Agbese at Newswatch, and the late Stanley Macebuh at The Guardian – tried to mitigate, if not bring to an end, by persuading Oparadike to change his mindset. Unfortunately, they did not succeed until he was replaced by the late Hajiya Bilkisu in late 1987.

The friction between the two of us came to a head during the Kafanchan riot. During the ensuing media war in defence of the students of their faiths between the Jama’atul Nasril Islam (JNI) and the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), the JNI felt it was not getting fair hearing from the New Nigerian because the editor was a Christian. It then decided to pay for a full-page advert to state its case.

That advert struck the federal authorities, in particular, the Directorate of State Security (DSS), as inciting and, apparently not being familiar with the workings of newspapers, picked up and detained Oparadike as editor. As soon as this came to my attention, I flew to the Lagos headquarters of the organisation where he was being detained, to explain to its officers that editors have no say in what gets published as advertisement. I told them that even though I had not seen the advert before its publication, I took full responsibility for it as managing director and the final word on the contents of the newspaper, whether it was news, opinion or advert.

There and then, the DSS released Oparadike and detained me. I remained in detention for almost a week before I was released to return to my seat. I never heard anything about the episode again until I was sacked in February 1989, almost two years after the event.

– Haruna was managing director of New Nigerian Newspapers in Kaduna