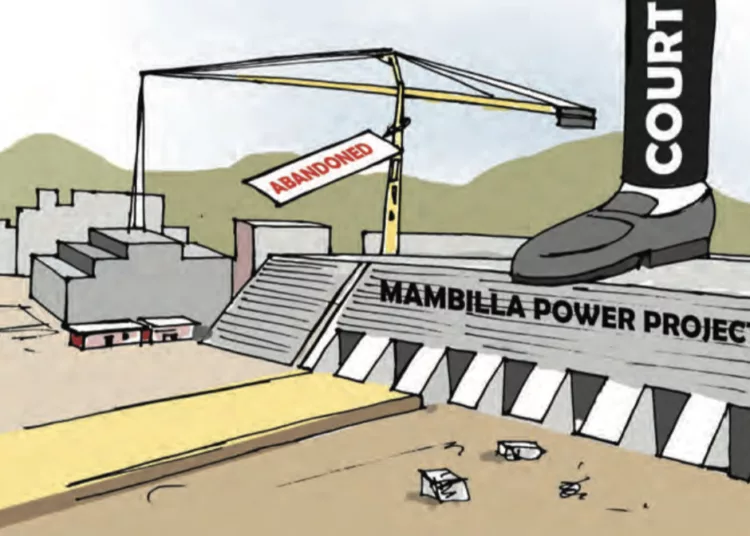

As Nigerians welcome the new year with high expectations in the midst of renewed hope, I join most citizens, especially residents of communities around the Mambilla Plateau in Taraba State, to ask: Will the Mambilla Hydropower Project ever come to fruition?

The euphoria that greeted the federal government’s decision to sign a contract for the project with Sunrise Power and Transmission Company Limited on a Build, Operate and Transfer (BOT) arrangement was palpable. But that optimism has long given way to cynicism.

It is disturbing that there appears to be no date in sight for the completion of this masterpiece project that was designed to comprise four dams and two underground powerhouses having 12 turbine generator units in total.

The project, no doubt, has huge potential and will, upon completion, positively impact on electricity supply nationwide, enhance productivity across all sectors, generate employment, boost tourism, engender technology transfer, improve rural development, enable irrigation, agriculture and food production in the area and beyond.

Sadly, over forty years after the project was originally conceived in 1972, we are still deliberating about its effective take-off when it ought to have been operational decades ago.

Essentially, the seemingly endless movement without motion as it pertains to the Mambilla Project shows how unserious successive administrations have been. It equally demonstrates clearly that the desire has never been to find a lasting solution to the challenge of power deficit.

Sometime last month, two senior lawyers-Afe Babalola and Wole Olanipekun, in separate official letters to the federal government, harped on the need for amicable resolution of the dispute over Mambilla Hydropower Project. Earlier this week, the Emir of Mambilla, Shehu Baju II, also lent his voice to the call for peaceful resolution of the dispute.

Sunrise Power and Transmission Company Limited had on October 10, 2017 dragged the federal government to the International Court of Arbitration administered by the International Chamber of Commerce, Paris, France, for alleged breach of contract in relation to a 2003 agreement to construct the 3,050MW Mambilla plant on a Build, Operate and Transfer basis for $6bn. Of course, the federal government insisted that due process was not followed in the contract award.

The lingering dispute is stalling the project and ultimately putting a snag in the efforts to harness the tremendous tourism and agricultural potential of the Mambilla Plateau. We are talking about a project that has the capacity to pull over 50,000 youths off the labour market through skilled jobs, a project that can generate 3.500mw of electricity and help in bridging the nation’s power deficit.

As the biggest single power project in the country, Mambilla will certainly chart a new course of prosperity for many, not just in Taraba State or the North East region, but in the entire nation. Government needs to step up efforts in resolving all the issues stalling the commencement of the project.

Like Mambilla, Like Farin Ruwa

One other project, which in spite of its enormous potential, has not seen the light of day like the Mambilla is the Farin Ruwa hydroelectric power project situated in Farin Ruwa, a sleepy community at Wamba local government area of Nasarawa State.

Conceived in 2001 to contribute about 40 megawatts of electricity to the national grid aside from serving as a tourism hub, the Farin Ruwa project was abandoned by successive administrations who deliberately refused to accelerate its completion.

It is difficult to rationalise the decision of successive administrations in Nasarawa State to abandon the Farin Ruwa Project considering its many benefits and the fact that the state has numerous communities without electricity.

Two decades after the project was conceived by the administration of former Governor Abdullahi Adamu, with huge resources committed to it, the Farin Ruwa Hydroelectric Power Project has also been movement without motion. There is very little or nothing to show for the enormous resources sunk into it.

Although the federal government took over the project in 2021, with an approval for its expansion to include a regional water supply scheme and construction of irrigation infrastructures of 2,000 hectares for dry season farming, work on the project has been moving at a very slow pace, further casting doubt on government preparedness to make the project come to fruition.

However, unlike Mambilla Project which is bogged down by litigation, Farin Ruwa is stalled by the lack of political will, pure and simple.

Unending Power Deficit

It is a given that power deficit is one of the major challenges confronting Nigeria where rural areas, urban slums and many small and medium enterprises which rely heavily on public power supply continue to bear the brunt of an epileptic power supply.

According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), no fewer than 640 million Africans lack access to power. Access to energy, the Bank noted, is essential to not only health and education, but also for reducing the cost of doing business and for unlocking economic potential and creating jobs.

Nothing underscores the enormity of Nigeria’s electricity deficit like the fact that an estimated 90 million Nigerians lack access to electricity supply. Sadly, there is nothing to suggest that the nation is on the verge of resolving challenges associated with provision of stable electricity for all, especially for those tenanting rural areas and urban slums.

Power supply in Nigeria is riddled with corruption, as humongous amount of money supposedly voted for the improvement of the sector is either mismanaged or outrightly stolen.

Of course, the need to boost power supply in the country informed government’s decision to mull the idea of the different power projects, including the much talked about Mambilla, which for decades has yet to take-off.

To effectively realise the current administration’s agenda, especially as it pertains to ensuring food security; eradicating poverty; job creation; access to capital; inclusion; rule of law, and fighting corruption, the federal government must accord topmost priority to power supply.

One sure way of demonstrating its commitment to power supply beyond the assent to the electricity bill is to hasten the process of resolving the lingering litigation over Mambilla Project, commit resources to, and ensure its timeous completion. Until that is done, we will continue asking: will the Mambilla Project ever come to fruition?