On July 15, 2024, The Gambia’s National Assembly decisively rejected a Bill that sought to repeal the 2015 ban on female genital mutilation (FGM). The vote was overwhelmingly in favour of maintaining the current law, with 48 members voting against the repeal and only 5 supporting it. This decision reflects the assembly’s commitment to upholding the 2015 legislation, which was initially introduced to protect women and girls from the harmful practice of FGM.

The ban on FGM in The Gambia was a significant milestone in the country’s efforts to promote gender equality and safeguard the rights of women and girls. The strong opposition to repealing the law indicates continued societal support for protecting these rights and combating gender-based violence.

A few weeks ago, Nigerians scuttled the Counter Subversion Bill and other related draft legislation. The Speaker of the House of Representatives, Abbas Tajudeen, withdrew the legislation after it had only passed the first reading. The Bill proposed a 25-year imprisonment or N10m fine, or both, for any person convicted of making a statement or taking an action that leads to separatist agitation or inter-group or sectional conflict in the country amongst others.

The Bill also stipulates that anyone found guilty of destroying national symbols, refusing to recite the national anthem and pledge, defacing a place of worship with intent to incite violence, or undermining the Federal Government shall face a fine of N5m, a 10-year prison sentence, or both. Many felt that the Bill if passed would threaten the fundamental rights of citizens and contradict the core principles of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and demonstration, that underpin any democratic society.

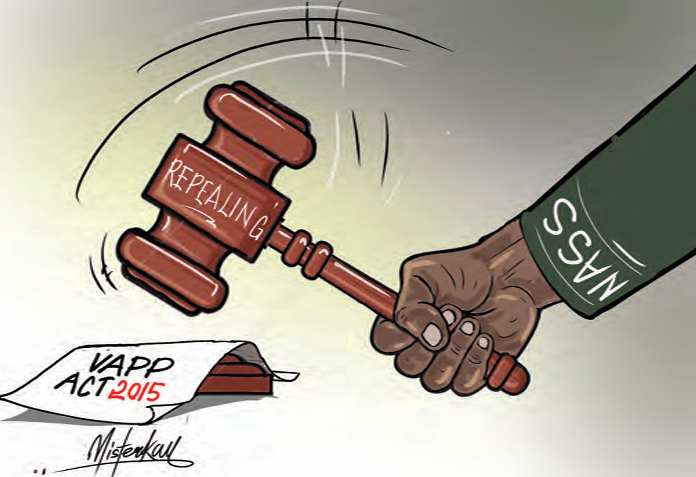

Nigeria now faces another legislative dilemma with the 10th National Assembly’s proposed repeal of the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act (VAPP) which has scaled second reading. Sadly, the legislators have failed to take into consideration the fact that the repeal of such a vital law could have profound implications for the protection of human rights and the fight against gender-based violence in Nigeria.

The VAPP Act 2015

The VAPP Act 2015 is a crucial piece of legislation in Nigeria aimed at addressing and preventing various forms of violence, including gender-based violence, domestic abuse, and harmful practices like female genital mutilation (FGM). The law, which was enacted in 2015, has been instrumental in providing legal protection and recourse for victims of violence. Since then, 35 states including the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja, have passed the Law except for Kano State.

Sponsored by Senator Jibrin Isah, Kogi East Senatorial District, the proposed legislation is “An act to Repeal the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act 2015, and to enact An Act to Eliminate Violence in Private and Public Life, Prohibit All Forms of Violence Against Persons and to Provide Maximum Protection and Effective Remedies for Victims and Punishment of Offenders, and or Related Matters”

This proposed repeal is a significant and controversial move, given the law’s role in protecting vulnerable individuals and promoting human rights. It has sparked widespread debate and opposition from human rights organizations, gender advocates, and the public who support the continued enforcement of laws that protect the vulnerable against violence and discrimination.

However, the repeal is not a recent move by the lawmakers, it has been going on for more than two years. The fact that the news is only gaining momentum should be a cause for concern about how such an important piece of legislation can elude the watchful eyes of citizens and activists who work within the context of critical legislation that promotes the rights of the vulnerable in society. Perhaps this is the intent of the lawmakers to avoid scrutiny and controversy.

The Bill waters down some of the strong language that ensured the law has more bite than bark with clearer context and definition of terms. The repeal will also mean that women’s rights activists and social justice advocates who campaigned for years to ensure the passage and assent across the states may have to go back to the advocacy drawing board.

Context Matters – Old Vs New

There are some contextual issues to consider. The National Assembly’s lack of consultation has led to widespread criticisms and suspicions. A more open and transparent process would have helped provide clarity for both sides to be able to come to some agreement on the Laws for an amendment rather than outright repeal.

For example, the proposed Bill clarifies the confusion over the punishment for rape by prescribing a minimum of 12 years and a maximum of life imprisonment. Due to an error in the VAPP Act, it is difficult to ascertain whether the punishment for rape is life imprisonment or whether it is a minimum of 12 years.

The Bill also creates new offences of attempting or conspiring to commit rape, as well as inciting, aiding, abetting, or counselling the commission of rape. It also provides for the establishment and management of a “Survivors of Violence Support Fund” which is to be funded from various sources including fines paid as punishment and properties forfeited for being used to perpetrate acts of violence. These provisions do not exist under the VAPP Act 2015.

However, there are downsides to the proposed Bill. In the VAPP Act 2015, Section 38(2) makes it a criminal offence for the head of any institution to infringe on the rights of a victim of violence, including expelling, disengaging, suspending, or punishing them in any form or manner for any action taken under the Act. The Bill omits this provision and thus exacerbates the already worsened state of vulnerability that survivors of violence face at work.

The Bill introduces a new section dedicated to sexual crimes against children thus removing them from the general protections afforded under the section on rape. So, rather than ensure enhanced protection for children in the new law, it diminishes the gravity of the offence of rape of minors. The offence of rape generally is set at a minimum of 12 years and a maximum of life imprisonment, raping a child aged 11 years attracts a maximum of 14 years imprisonment; raping a child aged 12 to 15 years attracts a maximum of 12 years imprisonment; and raping a child between 16 to 18 years attracts a maximum of 10 years imprisonment.

The implication here is that sexual predators and paedophiles will get a lesser sentence for sexual violence against minors. Reverting to defilement as rape of minors will only trivialise the enormity of the crime against minors and embolden perpetrators to do even worse.

The Baby And The Bath Water

While the proposed Bill may not affect the existing VAPP Laws at the subnational level because the 2015 VAPP Law is only applicable to the FCT Abuja and may only be enforced by the High Court of the FCT, Abuja, it may nonetheless erode gains made at the states.

The proposed repeal of the 2015 VAPP Act is ill-advised and should not be pursued further. Lawmakers cannot continue to propose laws and policies with deleterious consequences that effectively roll back or undermine progress towards protecting the vulnerable. If there are sections that need to be strengthened in the current VAPP Act, an amendment can take care of that.

The Legislature should rather redirect its efforts towards tackling the underlying factors that contribute to violence, strengthen the judiciary and law enforcement agencies to effectively prevent, respond and facilitate processes that ensures justice for survivors and consequences for perpetrators.